|

Part of the problem with my Record Collection Reconciliation posts to date is that I haven’t been upfront about the origins of these albums. 35 of the first 60 entries came from the same place and cost the same amount: $1. By my count, I own 332 total LPs from this place, all purchased for a buck, many of which are not typically found in dollar bins. I withheld this location from anyone I did not know personally for a very simple reason: competition. There was more than enough of that already.

Now that the magical well of cheap vinyl has long since dried out, I’ll reveal the secret: All of these records came from the Got Books Charity Book Warehouse in North Reading, MA, over the span of roughly two years. My first visit was in the summer of 2006, when my wife found a listing for a used book sale in the free weekly paper. I didn’t know they’d have records and the vinyl they did have on that first visit was forgettable enough not to mention. I did, however, grab a handful of interesting books, including a sixth-printing hardcover copy of Albert Camus’s The Plague with a badass embossed grim reaper on the cover. That kept me going back.

I might not have known about the sundries at stake if not for one of the warehouse’s employees, who casually informed me that you had to get there at opening Friday morning to get the fresh stock of vinyl. (Said employee later had to quit the job because of the high level of dust in the warehouse—I fortunately have shown no lasting effects.) The following week I arrived at 9am and saw a line of collectors/dealers, book and record alike. Once the door opened, they rushed to the vinyl racks in the side of the warehouse, weaving through the aisles of books. It was a swarm of balding locusts.

Let me temper your expectations, as mine were tempered again and again. All of the stock came in via donations, so the quality varied wildly based on the taste of people who’d donated, much like any Goodwill/Salvation Army/yard sale/thrift store you’ve ever visited, except on a much larger scale. Some weeks I’d find a cache of early ’70s jazz fusion, other weeks it might be Eno solo albums, but most people donated Barbara Streisand, John Denver, James Taylor, Ferrante & Teicher, and so forth. The week that truly hooked me was one of the first that I arrived early and found a pile of punk/post-punk classics: The Buzzcocks’ Singles Going Steady, Mission of Burma’s Signals Calls & Marches EP (original), the first three Gang of Four albums, Public Image Limited’s Second Edition, a few others. If not for competition from the bane of my existence (more on him shortly), I would’ve grabbed MOB’s Vs., too. It was a constant battle between hoping for specific records to show up and the reality of which ones always showed up, but trips like that one justified the commitment.

Yet I was never the only person scrounging for these records, so what I found often took second-place to what I saw other people grab.

The Competition

I love shopping for records, but I’d never thought of it as a competitive sport. If I had any hopes of grabbing the best stuff, I had to sharpen my game. I had to get to open racks first. I had to choose my first rack carefully, since it might the only one I’d have first dibs on. Unless I saw a great title at the front of a rack, I’d go for the one with the most colors on the top of the sleeves, since that indicated fewer dusty classical LPs and the potential for more recent fare. As I flipped through my rack as fast as possible, I had to keep my peripheral vision on the surrounding racks: What’s my next target? What’s the stock like today? What just got pulled? I had to memorize which racks I’d flipped through so that I got through all of the stock as quickly as possible. I learned to pull absolutely everything of interest and make the final decision at the end. There was no time to marvel at a find or linger on a potential winner. Grab everything as fast as you can.

The most important part of this game was knowing my opponents. The majority of them were local dealers, making their livelihood off their finds. By contrast, I was a graduate student trying to get a record fix on meager spending cash and build my collection. I grew to know my competitors a bit more each week, since they would talk shop waiting in line and compare finds after the fact. Here are the major players:

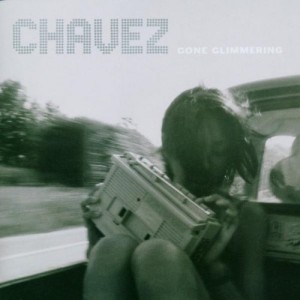

- The Bane: Three things gave the Bane his title. First, he was at the front of the line every week. I can only remember one week when he wasn’t there, and everyone else talked about his absence, especially his two book-dealer friends. I’d try to get there earlier than him, but it rarely worked. Second, he had some preternatural ability to find the records that most interested me and snag them first: Chavez’s Gone Glimmering, Wire’s A Bell Is a Cup…, Fugazi’s Repeater (although I found the inner sleeve, and in a decision born from vindictive angst, held onto it until he left). Third, I found his eBay store after he grabbed that copy of Mission of Burma’s Vs., and I’d check in on what he found and what it went for. This was the record-shopping equivalent of checking in on your ex-girlfriend on Facebook. Nothing good would come of it, but I’d do it anyway. Like a few of the other competitors, the Bane earned my begrudging respect and teeth-grinding hatred. He sped through the racks and only grabbed good stuff.

- The Couple: My second biggest competition was technically two people, since a young, 30-ish dealer brought his girlfriend most weeks. He was primarily interested in jazz LPs and hip-hop twelve-inches, but since he was a dealer, he’d grab anything else of interest / value. It’s likely ageist of me, but I found myself more concerned that younger dealers would recognize the merit of some late '70s or early '80s underground record than their older counterparts. The most frustrating score I witnessed was the girlfriend grabbing an original bound copy of Joy Division’s Still, thinking about it for a second, and putting it in her basket. When I ran into them selling records at the Somerville Rock 'n' Roll Yard Sale in the fall of 2008, I bought a reasonably priced copy of Eric Dolphy’s Out to Lunch, having a strong sense of his profit margin on it. He mentioned that he recognized me from somewhere, and had a laugh when I explained where.

- The Bottomless Pit: No, not Andy Cohen or Tim Midgett. This older dealer pulled absolutely everything out of the racks. If he had the slightly inkling of a record’s value or interest, it went into his heaping basket(s). You could tell if someone was new to the warehouse because they’d see a basket filled with good records, start flipping through them, and then hear the (potential) owner insist “Hello, those are mine.” He was a good spirit about it, which made sense considering his Grateful Dead obsession, but eventually he learned to put a jacket over the basket. Between his thin build, glasses, and hairstyle (balding, white hair but with a ponytail), he could have emerged from any number of local used record shops. Yet the drifter in him dominated; he’d relate stories of how many local Goodwill stores he’d hit up in the previous week. He would have been a stronger competitor if not for the toll that his genial interest had on his speed—he often stopped midway through a rack and pick up a conversation with a fellow dealer about some semi-obscure '60s rock record he just found.

- The Autograph Chaser: The other dealers were interested in records for their value as records, but the Autograph Chaser always looked a step ahead. He was mostly interested in classic rock and novelty records, since he could bring those to casino shows and book signings and presumably rake in the dough. My favorite overheard story was his absolute frustration with Stephen King, who had a reading in Harvard Square but refused to sign any books other than his newest. The Autograph Chaser waited around after the signing to follow King back to his hotel, but the inconsiderate author refused to sign any additional books. That Stephen King, what a dick!

- The Kid: He was one of the last regulars to show up during my time, a college-age kid from Lowell who loved ’70s classic rock. He was chummy with the other regulars, who were more than happy to pass along a worn Queen LP to him. He did have a streak as a dealer-in-training, relating how he bought a few hundred LPs from the backroom of a Lowell store in the hopes of flipping the valuable titles. He also had that Beatles completist streak that comes with every dealer—oh, the conversations they’d have if some remotely hard-to-find Beatles album came up.

- The Stereo Jack's guy: I didn’t recognize him at first, but soon overheard that one of the employees of Stereo Jack’s Records in Cambridge was a weekly visitor to the warehouse. It was strange knowing specifically where the records would show up, but as it turned out with the Bane and the Couple, this situation was not unique. (Sad news update: Stereo Jack’s will close in April.)

These were the most memorable people going to the warehouse every Friday, but I need to stress the gradual increase of attendees. When I started going in the mornings, I could get there at 8:50am and get a good-enough spot in line to snag an open rack. Over the course of the roughly two years I had to roll that back to 8:15am as the line grew from 15 to 50 people. Not all of them were there for the records—there were plenty of retirees stocking up on VHS tapes, book-dealers scouring the shelves for first editions, and even some people cross-checking every book with a bar-code scanner to find valuable titles for resale (I viewed this as cheating, but have since come around to the indispensable value of a smartphone while record shopping). It was like going from the minors to the pros.

The Finds

As I mentioned before, all of this would not have been worth it if not for the occasional gem. As bitterly as I look back upon my defeats, I can flip through my record collection and recall some victories. These may not be the rarest titles I found, but the stories behind them loom the largest.

- The match: I hated seeing someone else grab a wanted record, but the single most infuriating experience at the warehouse was coming across an empty sleeve. For some reason, this happened time and time again with Tom Waits albums. I’d find the sleeve for Swordfishtrombones, pick it up excitedly, and sigh at the missing weight of the vinyl (keep in mind this was before it was reissued). I’d put it in the basket on the off-chance that I’d find the vinyl in a white inner sleeve somewhere else in the racks, but that almost never happened. The exception was for The Smiths’ Strangeways Here We Come, my favorite of their full-lengths. I came across the sleeve (bearing a $4.50 price tag from Mystery Train), then frantically flipped through the racks until I stumbled upon the printed inner sleeve containing the record. I would’ve high-fived someone if I could have.

- The local cache: I’ve already mentioned how finding Mission of Burma’s Signals Calls and Marches EP was the first sign that this place was a keeper, but it wasn’t the last time I’d encounter one of Roger Miller’s projects. One week I grabbed two later Mission of Burma releases (Let There Be Burma and the self-titled EP), two No Man LPs, and a Birdsongs of the Mesozoic LP. Admittedly, most Boston-area used record stores are flooded with No Man vinyl, but at the time I felt thrilled to revisit that well.

- The seed: This entry could have been about any number of artists, since the warehouse filled in major, blinding gaps from the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s in my record collection. (A short list: Ornette Coleman, Herbie Hancock, The Replacements, The Rolling Stones, Minor Threat, David Bowie, Meat Puppets, Prince, XTC.) Yet one looms larger as a seed for future purchases. On a week when I found little, if anything else, nabbing the Cocteau Twins’ The Pink Opaque and Tiny Dynamite / Echoes on a Shallow Bay was a gateway drug to the group’s expansive discography. I never found another Cocteau Twins LP at the warehouse, no matter how much I’d hoped to stumble upon Heaven or Las Vegas, but it solidified my curiosity in the group after placing Treasure on my iPod Chicanery playlist.

- The snow haul: My dedication to the warehouse was always a bit stupid, but never more so than a trip up during a snowstorm. I justified it with “I’m driving against the flow of traffic” and left early to compensate, but still felt the clock rushing faster than the stop-and-go traffic. By the time I reached the warehouse, the doors had opened and the vultures had descended upon a particularly heavy load of records. I bolted to the back and sped through the vinyl as fast as I could, hitting pockets of interesting albums like four of Brian Eno’s first five solo releases and the first two Fugazi records. My final haul argued that the ends justified the means, but now I imagine what I would’ve been like if I only encountered Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass that day.

- The ’90s day: It took me a while to accept this fact, given my never-ending optimism that the zebra adorning Hum’s You’d Prefer an Astronaut would greet my from the middle of a rack and I’d hug the record and then chest-bump the nearby dealers, but vinyl was a niche product by 1989, let alone 1995. Cassettes and CDs had usurped the market share during the 1980s. This meant two things for post-1989 vinyl: first, there’s significantly less of it around; second, people who bought it were more likely to hold onto it. (The exception? DJs. They’d dump crates-full of black-sleeved hip-hop and dance singles once that movement had passed or their interest had waned.) Finding any rock record from the 1990s was a rarity. I only came away with one qualifying record from what I remember as ’90s day (Helium’s The Dirt of Luck, a favorite I’d owned on CD for years), since the Bane got that Chavez LP and the Couple nabbed Jon Spencer Blues Explosion’s Orange, but seeing all of those Matador titles was a tick of unfounded hope that I might encounter them again.

- The return: The feeding frenzy usually only lasted 15 minutes, by which point I’d seen all of the racks and was contemplating going through them a second time. I couldn’t narrow down my spoils (a process which seems ridiculous in hindsight—these are dollar records—but made sense at the time, since I often only had $10 in my wallet) at this point, though, since my decisions depended on seeing the results of the same process from my competitors. They rarely put anything good back, meaning that a slightly worn copy of some classic rock record might be the only addition to my pile. The exception was when someone—I want to say the Bane—put back an original copy of Dinosaur Jr.’s self-titled debut, back when they were just straight Dinosaur. I suspect that the name change might have thrown the original finder off the scent, but whatever the reason, I was thrilled it happened. (Of course, I would’ve been more ecstatic to grab a copy of You’re Living All Over Me or Bug, but I grabbed those on reissue later.)

- The rarities: I fully recognize that many of my picks are not particularly rare or valuable, but I knew immediately when I found two that were. Sometime during the spring of 2008, when the warehouse was blowing out its inventory, I found original pressings of the first two Big Star albums sitting near the front of a rack. I’ve been tempted to sell them ever since, especially after they were reissued, but I can’t bring myself to do it.

These are the exceptional stories, but most weeks it was a grind: flip through every record, find one of genuine interest and a few titles of relative interest, check out and drive home. Sometimes the records would all be leftovers and I’d come home with a few hardcover copies of Ernest Hemingway novels. Sometimes I’d convince myself to get a classic rock staple so I wouldn’t go home empty-handed. Every now and then there would be a huge week in which I’d bring home 20 records and realize that I’d eventually need to start a meme to get through all of them.

The Demise

I’ve mentioned that all of these records came from charitable donations, but what I’ve glossed over is Got Books’ business model. If you Google “Got Books,” the first auto-fill suggestion is “Got Books scam.” They’re a “for-profit professional fundraiser,” meaning that some of their proceeds go to help non-profit organizations. If you’re expecting all of the proceeds from these sales to go to charity—which you might, since Got Books’ omnipresent donation bins tout “books for charity”—you’ll be frustrated by the percentage that actually does. They do help worthy organizations, but I’ve never doubted for a second that they’re raking in money, especially when you compare what they looked like then with what they look like now.

Got Books’ inevitable expansion crippled the warehouse sale. After a few months of warnings and inventory clear-out (which I’ll close with), they moved from the North Reading location up to a larger building in Lawrence in June, 2008. The new building had a cleaner front-end—which felt like a store, not a warehouse—and more space to sort the truckloads of incoming books, videos, and records. Faced with a longer drive, increasingly spotty stock, and the advent of actual employment, I weaned myself off of my weekly visits.

Got Books also weaned themselves off of the free-for-all warehouse sales. In a series of changes reminiscent of Animal Farm, they recognized the potential for greater profit. Valuable books went up on Half.com. The warehouse store was replaced by a growing number of Used Book Superstores, in which varied (yet still cheap) pricing replaced the old dollar standard: typically $2 for a paperback, $3 for a hardcover. The records were split up between two of these locations (Salem, NH, and Danvers, MA) and given a confounding, color-coded system of pricing: something like $3 the first few days after new stock arrives, $2 the rest of that week, $1 or under after that point. This system penalizes the dealers to some extent, but if something’s actually rare, they’re still going to buy it. For me, rushing out to Danvers on a Thursday morning is neither feasible nor justifiable nowadays.

The Last Hurrah

The fall of Rome sounds like a singular event, but actually took place over hundreds of years. Similarly, although on a much smaller scale, the warehouse’s last hurrah lasted from the winter of 2007-08 into the spring. The available stock gradually increased with more racks, wall shelves, and boxes on the ground. But in some unknown, likely reformatted corner of my laptop hard drive, there’s a grainy cell phone camera picture that perfectly captures its tipping point. They’d opened up the massive curtains which separated the sale area from the sorting area, exposing enormous boxes (5’ by 5’ by 5’) of unsorted vinyl. I’d start by excavating one corner of the box, then hopped over the thick cardboard wall into the box and sorted through its contents. There wasn’t much dignity to the old method, but this arrangement felt like dumpster diving. And somewhere, there’s a photo of middle-aged dealers doing the same thing.

The problem was that the increase in volume didn’t guarantee miraculous finds, OG Big Star vinyl excluded. I remember pulling a few worthy records out of those enormous boxes—XTC’s Skylarking, Raekwon and Run-DMC twelve-inches—and otherwise being astonished by how much crap could be piled up. Prior to those trips, I’m sure I dreamed of swimming through endless dollar bins, finding exactly what I wanted, narrowly beating competitors to major scores, not seeing a single copy of James Taylor’s Flag. After them I likely had nightmares of being buried alive in tombs of Neil Diamond vinyl.

Perspective

There are other competitive forms of record shopping—the masses descending upon the record tents at the Pitchfork festival, local events like the Somerville Rock 'n' Roll Yard Sale—but nothing matches the consistent inconsistency of the Got Books Charity Warehouse. I still have a rush when I find some sought-after title at a record store, but I have to look at the price tag. I have to make a decision based upon that information. At the warehouse, if I saw Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz, I had essentially purchased Ornette Coleman’s Free Jazz. If I found twenty great records, I could come home with twenty great records without spending $150.

I’ve reiterated again and again the amount of standard dollar-bin fare that I encountered at the warehouse to underscore the sense that this was some mystical source of exclusively awesome records. It took the issues of every record store—varying quality of stock dependent upon recent acquisitions, other shoppers, location, and rate of turnover—and exploded them. Unless you live near Amoeba in San Francisco, it’s unwise to hit any record store too often for anything other than the just-in bin. You’re going to see the same sleeves. That was the beauty of the warehouse—I could go every week, see different shitty sleeves, and maintain a realistic hope that someone who had good taste back in 1982 cleaned out their garage.

|