1. Birdsongs of the Mesozoic - Magnetic Flip - Ace of Hearts, 1984

Why I Bought It: I grabbed this LP along with a handful of other post-Mission of Burma releases by Roger Miller, knowing little about it beyond Miller’s participation.

Verdict: Magnetic Flip attempts to merge Burma’s artier elements with modern classical compositions, bridging the gap between Miller’s stay in music school and his punk rock band. Using a forceful array of piano chords, organ leads, guitar textures, and drums, Birdsongs of the Mesozoic appropriate the Terry Riley/Steve Reich school of modern composition for a rock context, even naming one of the LP’s finest tracks “Terry Riley’s House.” A few of the songs touch upon Brian Eno’s instrumental work (according to Wikipedia, the band covered Eno’s “Sombre Reptiles”), giving an often claustrophobic mix room to breathe. The end result is intriguing, but often sonically overwhelming. I could have done without the reimagining of Stravinsky’s “(Excerpts from) The Rite of Spring,” which loads on too much dramatic tension for the already-laden aesthetic blueprint to stand, and the cover of the “Theme from Rocky and Bullwinkle” is curious at best. While I can appreciate the importance of forming an instrumental group in the early 1980s to push the boundaries of what independent/underground music could entail, I’d ultimately rather listen to Mission of Burma or Terry Riley than a combination of the two.

2. New Order - Confusion - Factory, 1983

Why I Bought It: In addition to my subconscious desire to hear four version of the same New Order track, I enjoy the graphic design of Factory sleeves and Confusion is no exception.

Verdict: “Confusion” isn’t my favorite New Order song, but having an instrumental version of it allows me to avoid one of Bernard Sumner’s most vacuous lyrics, “Ask me no questions, I’ll tell you no lies.” Additionally, the emphasis on electronic dance music in “Confusion” (DJ/hip-hop producer Arthur Baker had a hand in its composition) justifies the inclusion of a beats-only version and an instrumental version, which, amazingly enough, are noticeably different. The sleeve isn’t nearly as cool as the “Blue Monday” floppy-disk homage, but matching that iconic sleeve is a tall order.

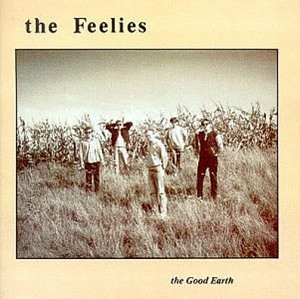

3. The Feelies - The Good Earth - Coyote, 1986

Why I Bought It: While I’ve never reached the point of obsession with the Feelies’ heralded debut Crazy Rhythms, I enjoy the record enough to try out its follow-up.

Verdict: The Good Earth starts off with a handful of relatively non-descript, jangle-heavy college-rock songs. While these songs are sonically inoffensive, they sound less like a band influencing their peers (namely R.E.M.) and more like a band being influenced by their peers, perhaps one playing catch-up after six years had passed since the release of Crazy Rhythms. Glenn Mercer’s vocals tend to settle into the music rather than peak nervously above it, the guitars rely too much on standard chord progressions, and the rhythms—even with two drummers—don’t match up with its predecessor’s namesake. Starting with the fourth track, “Slipping (Into Something),” the record shows signs of life. “Slipping (Into Something)” spreads out over six minutes, emphasizing its dueling melodic leads over the occasional jangle before accelerating into a fever pitch. “When Company Comes” returns to jangle mode, but the absence of percussion is a relaxing end to side A. Side B is consistently good, with highlights like the rhythmic pulse of “Two Rooms,” the electric leads of “Tomorrow Today,” and the quiet burn of the aptly titled “Slow Down.” Isolating these interesting elements of the Feelies’ sound helps me appreciate Crazy Rhythms more, since those elements comprise the vast majority of that album rather than the highlights of certain tracks. Still, for what seemed to be standard 1986 college rock midway through side A, The Good Earth has a great deal to offer beyond a new gateway to its superior predecessor.

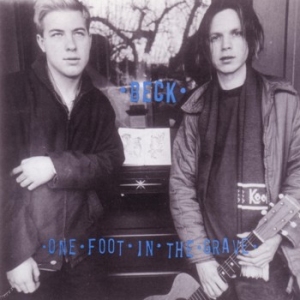

4. Beck - One Foot in the Grave - K, 1994

Why I Bought It: It’s significantly harder to find cheap, used vinyl pressed after 1990, so whenever I see anything resembling indie rock I’ll snap it up, particularly, like in this case, if I think it could be worth something on eBay. (While this record sells for up to $30, unfortunately there’s enough of a scratch on side A to prevent me from selling it.) I’ve never been a Beck devotee, but considering that my primary reason for this stance—my perception that Beck values style over substance in his genre-hopping exercises—doesn’t apply to a primarily acoustic endeavor, One Foot in the Grave might help me turn the corner on his work.

Verdict: Most of One Foot in the Grave sticks to a traditional folk/blues blueprint, relying heavily on Beck’s vocals, acoustic guitar, rudimentary drums, and the occasional counterpoint of K Records/Beat Happening honcho Calvin Johnson, who also produced the album. The few tracks closer to the lo-fi hodge-podge of Beck’s other early records linger on side A, which I listened to after the more stripped-down side B. There wasn’t a watershed moment of Beck appreciation, although I enjoyed “Girl Dreams,” “Hollow Log,” and “Asshole” (the lyrics of which were scribbled on the inner sleeve by the previous owner). I’ve admittedly had more fun skimming the Amazon reviews of the record, which sway from five-star odes to Beck’s “naked” album to poorly written one-star scoffs at its fidelity authored by “a kid” to this gem of a confused response, which is funny regardless of its possibly satirical intent. Where do I fit in to this glorious array of criticism? If One Foot in the Grave had been recorded in, say, 1997, after the success of Mellow Gold and Odelay, I would question its authenticity, tossing it aside as a cred-building exercise. But the timeline of its release is generous to Beck. Instead of figuring as a response to his musical surroundings or perceived audience demands, One Foot in the Grave comes off as a document of pre-stardom necessity. While the record is bolstered by Calvin Johnson, Presidents of the United States of America guitarist Chris Ballew, and Built to Spill drummer Scott Plouf, its appeal boils down to the limitations imposed by coffee houses and open mic nights. And honestly, I don’t frequent such establishments searching for the next Dylan, so I’ll take a handful of the better tracks and move along.

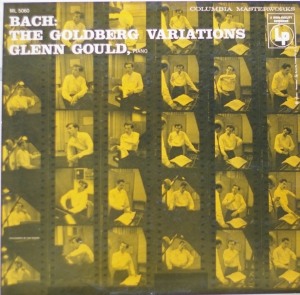

5. Glenn Gould - Bach: The Goldberg Variations - Columbia Masterworks, 1956

Why I Bought It: Two separate anecdotes: The first time I heard Glenn Gould’s name was when I read Giorgio Agamben’s The Coming Community in an Agamben/Kristeva seminar during graduate school. Agamben mentions Gould in a section about potentiality, essentially stating that Gould’s retreat from live performance into the studio emphasized the capacity to perform and not perform at the same time. (I could relate this concept more fully, but I’d rather avoid scouring my hard drive for a short paper on the topic.) Shortly after this instance, my mom read Gabriel Josipovici’s novel The Goldberg Variations and asked me if I could track down a copy of its musical namesake. After downloading a harpsichord rendition of the piece (the instrument the piece was written for, but I shudder at the thought of hearing a harpsichord), I grabbed Glenn Gould’s piano performance. A few months later I found the LP.

Verdict: Given that I hadn’t heard Glenn Gould’s name until a year ago, I won’t embarrass myself by critiquing his performance or J. S. Bach’s composition, although according to Wikipedia Gould himself “later came to criticize his early off-beat and lyrical interpretation, expressing reservations about its pianistic affectation, overt emotionalism, and lack of temporal unity.” I mean, I hadn’t even thought to do any of that. For my purposes, The Goldberg Variations is too busy to accompany reading, since the thirty separate variations switch up the pace frequently enough to gain my attention. Damn you, Bach and Gould, for daring to pull my attention from The Trouser Press Guide to ’90s Rock. It’s hard not to be impressed by both composer and performer, however, so I’ll continue to pick up Gould performances on the cheap—I have at least one more in the queue—but finding the right time to listen to them may be the biggest challenge.

|