Roughly twenty-five years ago I taped a song off the radio, rewound endlessly to replay it, and then made it my mission to buy a copy of the CD during a high-school trip to Boston. I begrudgingly paid the outrageous sum of $17.99 for a copy of Hum’s You’d Prefer an Astronaut at the Tower Records in Harvard Square—it was out of stock at the nearby Newbury Comics—and, not yet owning a portable CD player, waited anxiously to get home so I could hear the rest of the album.

Over the next days, months, and years, I more than made up for that excruciating delay. I dubbed the CD to one side of a blank cassette and ground its fidelity to mush as I transported myself out of myriad high-school bus rides. The appeal of the introductory single “Stars” was twofold: its massive riffs were bracingly huge, bolstered by a steady undercurrent of compelling textures and melodic leads, but Matt Talbott’s vocals and lyrics eschewed the posturing attitude commonly associated with “heavy” music. The head-fake intro (memorably skewered by Butt-Head: “It sucked but at least it was short”) was quiet and thoughtful, and those qualities remained once the song fully kicked in. The rest of You’d Prefer an Astronaut spiraled out from this combination of overflowing guitars and ponderous, evocative lyrics. Its romantic notions were filtered through stargazing or space-bound narratives, and the album’s lingering threat is becoming untethered, both in literal and relational senses. Hum proved equally adept at meditative mid-tempos (the enveloping drone of “Little Dipper,” the psychedelic imagery and polychromatic tones of “Suicide Machine”), surging rockers (the dark intensity of “The Pod,” the soaring arcs of “I’d Like Your Hair Long”), and ambling odes (“Songs of Farewell and Departure”). You’d Prefer an Astronaut offered familiarity and escape.

You’d Prefer an Astronaut felt like a self-contained world, but after going online and finding their web page (http://www.prairienet.org/~hum/, flaunting a sub-directory and a tilde), I worked my way to Urbana, Illinois' Parasol Mail Order, which offered their earlier records, their t-shirts, related bands, and aesthetically similar bands. I learned how the band went through numerous personnel changes before recording its 1991 debut, Fillet Show, whose groaning pun of a title is an accurate indicator of its contents’ (cough) rather considerable room for growth. After guitarist Balthazar de Lay left to front his own band, Mother (later renamed Menthol), Hum finalized its lineup by adding the youthful Tim Lash on guitar and comparative veteran Jeff Dimpsey on bass (he’d previously played guitar in Champaign-Urbana mainstays the Poster Children and Hum’s brother band, Honcho Overload, alongside bassist Matt Talbott). Thanks to these new additions, 1993’s Electra 2000 was a significant step forward, worthy of being dubbed to the opposite side of my You’d Prefer an Astronaut cassette. Electra is a dynamic, bruising album, driven by the chugging riffs of highlights “Iron Clad Lou,” “Sundress,” and “Winder.” It’s jarring to work backwards to Talbott’s throat-shredding desperation, that approach having been whittled down to a single scream on You’d Prefer an Astronaut’s “The Pod,” and even on its best tracks, Electra 2000’s tonal palette is monochromatic. However raw and comparatively unpolished it may be, Electra 2000 still holds up, especially “Diffuse,” a compilation track added to the 1997 Martians Go Home! CD pressing.

The other breadcrumbs I followed proved that Hum did not exist in a vacuum, that You’d Prefer an Astronaut did not materialize out of thin air. Matt Talbott’s list of his favorite records on Hum’s page (from memory, a cross-selection of turn-of-the-decade indie/alternative guitar rock: Dinosaur Jr.’s Bug, The Flaming Lips’ In a Priest Driven Ambulance, My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, and half a dozen others I’m less certain of, like Mercury Rev, Swervedriver, and Bitch Magnet) traced one side of their development, and the sonic similarities and shared members of various notable bands from Champaign-Urbana and other significant Midwest college towns tracked another. A communal affinity for thick guitar sounds could be found on Poster Children’s Daisychain Reaction (their lone album featuring Jeff Dimpsey and arguably their heaviest), Honcho Overload’s Pour Another Drink, Zoom’s self-titled debut (Matt Talbott is referenced by name on the jittery “Ephedrine Breakfast” from the band’s second LP, Helium Octipede), and Love Cup’s Greefus Groinks and Sheet (an album still discussed in hushed reverence by people who were there, and also me, who was not). Hum’s evolution from Fillet Show to Electra 2000 makes more sense when contextualized within a regional Midwestern sound. And if You’d Prefer an Astronaut used a major-label recording budget to realize a sound previously out of reach to the group, it’s noteworthy to Talbott’s list of favorites that Flaming Lips producer Keith Cleversley was at the helm.

Hum may have existed within a community of like-minds, but my high school provided no such comforts. No one in my social circle had any interest in going deeper into the alternative / indie waters, so band mailing lists and IRC channels were godsends. The members of Hum did not frequent the band’s semi-official listserv (leaving such future-signaling fan/band interactions to the Poster Children) or #hum (back when hashtags were associated with IRC channels), but I found plenty of great people in similar situations. Like a half-dozen others, I did my service by running a Hum fan site, collecting lyrics, photos, and links to supplement Hum’s skeletal web presence.

Hum’s next album, Downward Is Heavenward, didn’t come out until early 1998. Their perfectionist tendencies took precedence over striking while the iron was hot, and Downward was reportedly recorded twice: first with YPAA producer Keith Cleversley, then with Mark Rubel in Champaign. My previews came from the early demo of “Ms. Lazarus” on the CD5 for “The Pod” (a warm, unfussy run-through of an endlessly endearing track) and a third- or fourth-generation cassette of a live show featuring an embryonic version of “Comin’ Home” (not specifically this one, but here's another 1995 performance of it) which sounded far rawer in its infancy (and/or compromised fidelity) and offered an entirely different chorus (“I’ll treat you like a sound,” which I heard for years as “I’ll treat you like a son”). As the release date approached, fan sites got to post 30-second samples of songs—either in the streamable muck of the briefly in-vogue RealAudio format or the comparative clarity of the nascent, bandwidth-punishing mp3 format—and I obsessed over too-short tastes of “Dreamboat” and “Green to Me.” I ordered the vinyl from Parasol because it was coming out at least a week before the CD hit stores, and patiently waited for it to arrive.

Hearing Downward Is Heavenward for the first time was vastly different from my initial spin of You’d Prefer an Astronaut; I had expectations, I’d heard plenty of other excellent bands and records in the intervening years, and my listen was tempered by the group-think of an internet community. I loved it, but my appreciation wasn’t unqualified. The production sheen felt too glossy in comparison to the mid-fi warmth of You’d Prefer an Astronaut. Not every song clicked immediately (looking at you, “The Scientists”). My hopes for a blistering “Comin’ Home” and an enveloping, intimate “Ms. Lazarus”—what I’d already heard, essentially—were dashed. Those hints of resistance, of grasping onto how much my decaying cassette dub of You’d Prefer an Astronaut meant to my bus rides, were on me, not the band. Eventually I got over it with the help of an eardrum-punishing performance at Irving Plaza in New York City (during my moronic phase of being Too Cool for Earplugs), and I could appreciate Downward Is Heavenward for being different from You’d Prefer an Astronaut. The depth of “Isle of the Cheetah” was like a time-lapse video of organic life taking hold of an abandoned structure. “Ms. Lazarus” needed the extra oomph to fully surge in its final section. “Afternoon with the Axolotls” (though lacking its superlative live intro) was thoughtful and explorative. The double-punch of romance and riffs provided by “Dreamboat” and “The Inuit Promise” made me long for the chance to meet new people I might actually connect with. The deftly recorded reverb of “Apollo” made its ache that much more powerful.

Downward Is Heavenward didn’t come close to replicating the commercial success of You’d Prefer an Astronaut. The sci-fi video for lead single “Comin’ Home” was rejected by MTV’s 12 Angry Viewers, one of the network’s shows designed to combat the (accurate) criticism that it aired a diminishing selection of music videos, and second single “Green to Me” gained no traction. The tides were against them: “alternative rock” skewed more and more “pop” (big singles that year included Semisonic’s “Closing Time,” Barenaked Ladies’ “One Week,” and The Offspring’s “Pretty Fly [For a White Guy]”); nu-metal was on the rise with the multiple-platinum success of Korn’s Follow the Leader; and Total Request Live pushed the most popular videos to even greater ubiquity. Meanwhile, Hum’s van was wrecked during a June tour through Canada, forcing the cancellation of most of the remaining dates. The band sounded exhausted in interviews, fully aware of the writing on the wall.

Hum never released an official statement about breaking up or going on hiatus, but after only playing one show in 1999 and two in 2000, they entered cryo-sleep following an opening slot for The Flaming Lips’ New Year’s Eve show at the Metro in Chicago. The members went their separate ways: Matt Talbott formed Centaur with Castor bassist Derek Niedringhaus and drummer Jim Kelly; Tim Lash started Glifted with Love Cup’s T.J. Harrison; Jeff Dimpsey revived the whispered-about Champaign group National Skyline with Castor’s Jeff Garber; and Bryan St. Pere moved to Indiana for a pharmaceutical job. Centaur and Glifted bifurcated Hum’s DNA for their respective 2002 albums. Centaur’s In Streams took a mournful approach to Hum’s foundations, repeating its big riffs over Matt Talbott’s reserved vocals. (I saw Centaur a number of times, but their curtailed opening set for Shiner in St. Louis is seared into my brain, specifically Talbott sighing “Our band is in this [malfunctioning] pedal” while nursing a comically huge bottle of beer.) Glifted’s Under and In emptied a warehouse of head-spinning metallic shoegaze riffs, with the surprising addition of falsetto vocal hooks on some songs. But each band possessed what the other lacked: Centaur needed Tim Lash’s inventive guitar parts to break the repetition, while Glifted needed Matt Talbott’s emotional resonance and structural support to channel great parts into great songs. Dimpsey’s National Skyline was the best of these projects, particularly their 2000 self-titled EP and 2001’s This = Everything, which simultaneously looked back to U2’s The Unforgettable Fire and ahead to the icy, electronic-bolstered post-emo of groups like Antarctica. But Dimpsey never toured with National Skyline, and that group, too, went on hiatus during Garber’s move to Los Angeles to join Failure’s Ken Andrews in Year of the Rabbit (and later form The Joy Circuit). A second wave of projects appeared in the late ’00s, with Tim Lash forming Balisong and Alpha Mile (no studio recordings, but live footage exists for the latter) and Jeff Dimpsey teaming with Absinthe Blind’s Adam Fein for Gazelle, releasing Sunblown in 2008.

Even in ostensible hiatus, Hum still emerged every few years. Furnace Fest called their asking-price bluff in 2003, and their headlining set was preceded by a local warm-up in Champaign. Sporadic regional dates occurred in 2005 and 2008–2009 (I saw their New Year’s Day show in Chicago), picking up in 2011 around the time of the FunFunFun Festival. Two unreleased songs—“Inklings” and “Cloud City”—frequented their sets at these shows, and I attempted to will a seven-inch with studio recordings into existence. A co-headlining tour with Failure in 2015 marked the most significant action since the release of Downward Is Heavenward. Bryan St. Pere opted out of this tour, aptly replaced by Shiner’s Jason Gerkin, and a year later, the band confirmed that they were working on new material. The still-unreleased “Voyager 1” started appearing in 2016. When I saw them (with St. Pere back in the band) in St. Louis in early 2018 (sharing a bill with a reunited Castor!), they unveiled a few new-new songs: “Folding,” “The Summoning,” and an instrumental version of “In the Den,” none of which felt fully formed yet.

The idea of Hum releasing new material was always within the realm of possibility, but turning that promise into actuality was a harder proposition to grasp. Given that Matt Talbott owns and operates his own studio (Earth Analog in Tolono, IL, formerly known as Great Western Record Recorders), the logistics for recording were mostly handled. But the band’s timetable-tipping perfectionism made any hypothetical release date seem impossibly optimistic. Said trait dates back to both of their RCA albums, but resurfaced more recently with regards to vinyl reissues. Talbott was understandably miffed at ShopRadioCast having snaked the reissue rights for You’d Prefer an Astronaut in 2013 and not involving the band in the (assuredly CD-sourced, decidedly shitty) pressing. So the 2LP reissue of Downward is Heavenward opted against a cash-grab rush-job and for an extraordinarily patient, results-oriented process. After years of rejected test pressings and other delays, it finally came out in 2018 on Talbott’s own Earth Analog Records (the second pressing on blue vinyl appears to still be available), and was worth every penny. Whereas the original pressing crammed too much music onto a single LP, the reissue gave the songs room to breathe, and the new mastering job added depth and clarity. Adding “Puppets,” “Aphids,” and “Boy with Stick” as bonus tracks on the fourth side was greatly appreciated. The end result was worth the wait, but it didn’t exactly give hope that the new Hum album would appear anytime soon, even with rumblings that “it’s done except for a few vocals.” An added wrinkle came with the news that Talbott was working on a solo album to complement his living room tours (remember touring?), an album that might somehow come out before the Hum record. Early versions of “Sinister Webs” and the sprawling drone “Way Up Here” popped up on Bandcamp, giving the project the proof of life.

And then that mythic new Hum album just… appeared. Inlet was surprise-released on June 23, 2020 on Bandcamp and presumably also lesser digital outlets, and the Earth Analog–pressed vinyl was available for preorder through Polyvinyl (a wise choice after the early blink-and-you-missed-it drops of the Downward Is Heavenward reissue brought both Talbott and eager fans much consternation). It was a blinding ray of sunlight amidst the endless drudgery of quarantine life, a bona fide event to make up for the fact that calendars had been wiped clear for months. Texts were sent and received as I carved time out of my child-watching schedule to actually listen to the album. Around that time the chatter switched from “whoa there’s a new Hum album” to “whoa the new Hum album is great.”

And it is great.

Inlet’s surprise drop reversed my expectations-burdened introduction to Downward Is Heavenward. Even with the knowledge that Inlet would arrive at some point, the twenty-two years of distance from Downward and all of the offshoot projects—satisfying, underwhelming, and forgotten alike—wiped the slate clean for both this fan and the band. I wasn’t paralyzed by comparing subjective quality, while Hum weren’t boxed in for their next moves. I’ve seen a few people assert that Inlet could have easily come out a year or two after Downward and I respectfully disagree; the ways in which Hum’s sound and perspective have shifted depend on that timeframe. The songs are longer, with stretches of meditative repetition drawn from stoner/doom metal. Matt Talbott’s lyrics largely trade the brightness of Downward highlights like “Dreamboat” for a lived poetic perspective on his fleeting place within nature, within humanity, within the galaxy, like Mount Eerie’s Phil Elverum writing bittersweet sci-fi memoirs. Inlet isn’t disconnected or displaced from the continuity of Electra 2000, You’d Prefer an Astronaut, and Downward Is Heavenward—there are riff-churning, melodically buoyant tracks here, don’t worry—but like Polvo’s return albums In Prism and Siberia, Inlet exhibits a band that did not stop evolving, even if the signposts of studio recordings did not appear to document that journey.

The eight tracks on Inlet sift into three different modes: mid-tempo melodic rockers, ultra-heavy evocations of stoner metal, and ponderous, introspective odes. The first category is the most populous, offering “Waves,” “In the Den,” “Step into You,” and “Cloud City.” (“Inklings” is curiously absent from Inlet, perhaps viewed as remnant of Downward instead of a step forward.) As much as I’ll argue that Inlet doesn’t exclusively traffic in the nostalgic thrall of a classic sound captured in amber, there’s no denying the dopamine rush of that guitar sound when the post-Loveless arcs of “Waves” hit. Those layers of immaculately crafted guitars offer an immediate, resuscitative balm, continuing to reveal new overdubs on the tenth, fifteenth, twentieth spin. “Waves” looks back upon past, unspoken struggles (“They don’t know of my solitary days”) as Talbott gazes off into an uncertain future, but there’s a comforting serenity to this distanced perspective as the song churns and crests, closing with “To see beyond the boiling sun / To the other side / And the wonders didn’t end.” The lack of an emphatic, hooky chorus in “Waves” (an element Hum deprioritizes for much of Inlet) is quickly rectified by “In the Den,” which offers the album’s most catchiest refrain. It’s hard not to appreciate “I am still alive and what's coming true / Is the signal to my return, oh! / Find me here on the ground and in need of you” as a meta-level statement on Hum’s reappearance, and the liveliness of that “Oh!” cannot be understated. If Inlet came out on a major label, there would assuredly be a single edit for “In the Den,” which rides its soaring riff almost seven minutes before fading out, but Hum’s propensity for savoring its work doesn't tip against the listener’s favor. “Step into You” is Inlet’s shortest song at just over four minutes and its most conventionally structured, switching between a satisfyingly chunky verse riff, a slowed-down chorus progression, and a silvery guitar solo. In contrast, “Cloud City” lets its sci-fi tinged verses (“Crowds would gather on the traces of the outer rings”) give way to the tremendous gravitational pull of the guitar workout black-hole where a chorus might have once lived, fueled by Bryan St. Pere’s best, most pummeling work on Inlet.

While those four songs offer a comfort-food buffet for starving Hum fans, “Desert Rambler” and “The Summoning” expand the menu’s offerings. The stylistic stamp of stoner/doom metal on Inlet is not without precedence: Matt Talbott’s bar Loose Cobra in Tolono, IL, has hosted Oktstoner Festival, and it’s a natural progression from the skeletal riff-and-repeat approach of Centaur’s songs. I recall being at Parasol after Centaur had played a show in Chicago with Pelican (having just released their untitled debut EP) and drummer Jim Kelly sang the band’s praises. It wasn’t a one-way relationship—the leads of the title track to City of Echoes demonstrate how much Pelican drew from Hum—and it’s on these songs that Hum reflects back upon some of the bands they influenced and remain within their orbit, whether that’s the continent-shifting churn of early Pelican, the metal-tinged instrumental rock of Ring, Cicada offshoot Dibiase (who’ve released an EP and an LP on Talbott’s Earth Analog Records), or the heavy slow-core group Cloakroom (who chose Talbott to produce their 2015 LP Further Out and got him to sing lead vocals for their b-side “Dream Warden”). “Desert Rambler” spans nine minutes, alternating between a mammoth verse riff that Talbott nearly has to bellow over and dreamy, barren bridges and choruses. Even before chiming notes swoop over the top of the machinery, there’s a impressive build-up of undercurrent textures (to the mystifying chagrin of the otherwise satiated Stephen Malkmus, a comment which at last connected my high-school fondness of both Hum and Pavement). “The Summoning” is somehow heavier and slower (who do they think they are, Pinebender?), but even with the foreboding crush of its main riff and the serrated edge of the harmonic accents, Talbott’s sheepish nature (“Let this be the last assumption that you were never wrong / I am ever wrong”) and detached perspective (“Just a twist and I'm gone / Through the ether and on to home”) offer a variation on the juxtaposition between form and content that initially drew me to Hum’s music. Given how Hum’s aesthetic leap on Electra 2000 was driven by predecessors and peers, adding the influence of their protégés on “Desert Rambler” and “The Summoning” while still scanning as Hum songs feels fitting.

Inlet’s final two songs are my clear favorites on the record, applying the analgesic guitar tones of the up-tempo tracks to the sprawling terrain of the Mesozoic stompers, and uncovering new lyrical depth in the process. “Folding” and “Shapeshifter” each stretch to eight minutes, hinging upon a very relatable combination of overwhelmed by what might come next and comforted by the lasting resonance of his loving relationship. “Folding” weaves a melodic lead around Talbott’s ponderous verses—“Do you feel tremors here? / Do you feel the same like you used to?”—then lets Jeff Dimpsey’s undulating bass line take hold before asserting “I could never be two / I’ve got it in for you” in the shimmering coda. The last two minutes of “Folding” quietly pulse as delay-drenched scrapes curl overhead, a ruminative enclave before Inlet’s closing track. “Shapeshifter” allows its evocative guitar line to play out in full before Talbott’s vocals come in, and there’s no better encapsulation of his lyrical appeal than its opening verse:

I remember the skies and the sand

I remember your face and your lovely hand

Words poured out on a dusty land

And gravity comes to us all

I feel the engines stall

Feel us start to fall

The chorus of “Shapeshifter” elongates its syllables into an immersive wash, floating over a slow-moving sunset. The bittersweet bridge—“While you let the water in / I dreamt again that I couldn’t swim”—builds into a C-Clamp-esque plateau of sustained guitar, and then switches to the cleaner chords of the song’s back half. The titular shapeshifting occurs as Talbott envisions himself as a butterfly, a fawn, and a bird, a fanciful sequence motivated by “Finding myself past the half-life of me” and pondering other forms of existence. This passage ties together the recurring themes of Inlet, and the record ends with the warmth of “Suddenly me just here back on the land / Reaching for you and finding your hand.” These two songs are part of a lineage with “Suicide Machine” and “Ms. Lazarus,” but the imagery has been refined, the emphasis on mortality no longer feels hypothetical, and there’s no drama within the relationship, only calming reassurance.

Listening to Inlet enacts a strange push-and-pull of going back and moving forward. I’m transported back to my high school days, to when my fondness for this band was at its most consuming, but I’m not trapped back in 1997, just recalling the past as the past. My enjoyment of Inlet isn’t dependent upon that timeframe: the album doesn’t resonate with me now solely because it would have resonated with me then. It resonates with me more now than it would have in high school. That’s a rare achievement for reunited bands (joining successes like Polvo and Slowdive), which involves passing up the easy move of wearing their glory days like an old t-shirt, regardless of whether it still fits. Sometimes that shirt does still fit, giving fans a swell of nostalgia for a rose-colored era and the band a rush of renewed adulation, but those swells and rushes subside as the present regains its focus. Inlet’s lyrics never inhabit the past. They look back, sure—the chorus of “Step into You” begins “Remember how / Your voice was an echo to me”—but Matt Talbott doesn’t write like he’s returned to his twenties or thirties. The same song rejects the temptation of writing from the past, closing its first two memory-chasing verses with “And everything here isn’t true” and signing off with “I am over it / I’m a dried-up, wind-blown cocoon.” Talbott is at peace with where he is now, and that’s where Inlet’s songs reside.

I’ll never experience Inlet with the same singular focus as I did You’d Prefer an Astronaut with the dubbed cassette and the daily bus rides and the feeling of entering an unfamiliar-yet-familiar world and staying there, but Inlet offers a different path to residing within the album on its own terms. While Hum’s fan base cheerfully revisits the past to help process Inlet (ahem), the band declines that journey. They delivered the album and backed off. There’s been a notable absence of promotional interviews for Inlet, with Bryan St. Pere’s pleasant, if not especially revelatory 2018 appearance on Joe Wong’s The Trap Set podcast remaining the most helpful link I can pass along. (Fingers crossed for a Matt Talbott appearance on Allen Epley’s Third Gear Scratch podcast, comparing notes over how Hum approached Inlet and Shiner approached their own reunion record, Schadenfreude.) There are no lyrics included with Inlet and only the barest credits on the album’s gatefold sleeve, let alone explanatory liner notes. No song-by-song walkthroughs exist to provide insight, no Reddit AMA to answer fan questions. No promotional videos. No livestreamed performances. No advance singles with exclusive debuts. Given how uncomfortable the members of Hum appeared with the machinations of major-label life—that awkward interview with noted fan Howard Stern, Matt Talbott and Tim Lash’s inexplicable chicken and bunny suits on 120 Minutes, their clear disinterest in fashionable turns like the Smashing Pumpkins’ goth-glam makeover for Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness—and how their only priorities seemed to be recording (and possibly re-recording) albums and crushing audiences with massive volume levels, it’s not a surprise that the band abandoned the promotional circus. Inlet is entirely on Hum’s terms: recorded at Talbott’s studio by Talbott, Lash, and Earth Analog house engineer James Treichler, mixed by Lash, released on Talbott’s label. No guest musicians, no outside producer. What’s absent is significant. It’s a bold gambit, dependent upon the size and voracity of the band’s audience. They delivered the album, this album. That’s enough.

I won’t provide a final verdict on Inlet or a qualitative ranking of Hum’s albums; I spent over twenty years with You’d Prefer an Astronaut and Downward Is Heavenward, so calling Inlet after five months seems cruelly premature. It’s an ongoing process, one that will continue after tour dates safely reappear and my eardrums have been bludgeoned by full-volume renditions of these still-new songs. I am, however, willing to declare my lingering astonishment over Inlet. I should not have been this surprised—there were good reasons why they held the title of my favorite band for a long time—and yet Hum was not content to merely remind me of those reasons. Much of their critical legacy is bound to a specific guitar sound, one that could be distilled, purified, and injected into a Deftones album, and Inlet both demonstrates how breathtaking the genuine article of that guitar sound can still be and reinforces the singularity of their songwriting, which continued to evolve in absentia. No matter how many bands have emulated Hum, only one band can write songs like “Folding” or “Shapeshifter.”

|

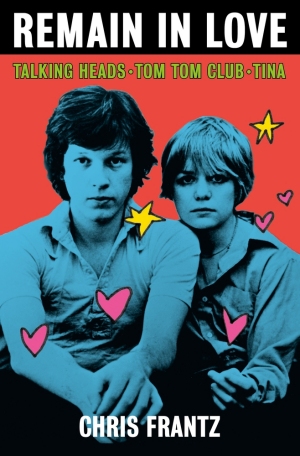

The name of this memoir is Remain in Love, a dual reference to Talking Heads’ finest album, 1980’s Remain in Light, and Chris Frantz’s forty-plus years of marriage to Tina Weymouth, his bandmate in both Talking Heads and Tom Tom Club. But if you’re a fan weighing the prospect of uncovering more behind-the-scenes acrimony between the rest of the band and David Byrne, the title hits differently. Will the expected vilification of Byrne soil the band’s legacy, Byrne’s legacy, or both? Is Remain in Love something you should avoid if you want to, uh, you know?

Well, yes, you should avoid Remain in Love, but not for the perceived threat to your enjoyment of the Talking Heads catalog. Remain in Love is a trying, often tedious book, and David Byrne does not come off particularly well in it, but those two aspects are not bound in the way I expected. I didn’t put the book down every couple of pages during its momentum-defying middle because I was dreading the revelation of some new misgiving from Byrne; I kept putting the book down because it was flat, uninsightful, and repetitive. I kept putting the book down because its narrative felt overtly filtered through the page-one assertion that “You could say that Tina and I were the team who made David Byrne famous,” a push to reclaim the band’s legacy from the supposed sole ownership of David Byrne. (Sorry, Jerry Harrison.) The degree to which the chip on Frantz’s shoulder—deserved or not—determined what the book would cover and how major players would be depicted, including Frantz himself, greatly limited any potential insights.

Allow me to take stock of those major players:

Jerry Harrison: The new owner of the “Most underappreciated member of Talking Heads” belt, Jerry Harrison is sidelined for most of Remain in Love. It’s understandable to an extent—he didn’t go to RISD, joined the band after they were somewhat established in NYC, and was neither married to nor an enemy of another member—but if you’re hoping to learn anything about Harrison beyond his previous tenure in the Modern Lovers, his occasional horniness, his brief depression and substance issues during the recording of Speaking in Tongues, or his taste in tour bus literature, prepare to be disappointed. Outside of the book I learned that Harrison was preparing to tour Remain in Light for its 40th anniversary with guitarist Adrian Belew and the band Turkuaz. I assume that tour, like all things, has been postponed indefinitely, but it was nice to read about his cordial relationship with David Byrne.

Johnny Ramone: If Remain in Love has a villain beyond David Byrne, it’s the Ramones guitarist, who was physically abusive with his girlfriend as he sulked his way through a European tour with Talking Heads. (Did he want to see Stonehenge? He did not.) This Frantz takedown, however, is thoroughly odd: “Johnny was still angry at us about our love of art, history, and culture. He said so as if this was ruining his life. I just looked at him and said, ‘Johnny, this tour will be over soon. Let me just say, in spite of all your bad moods, we are very happy to be here with your guys and one day you will realize that we are the best opening act you have ever had or will ever have.’” Did either side of that conversation take place?

Brian Eno: The producer of More Songs About Buildings and Food, Fear of Music, and Remain in Light starts off as a breath of fresh air and proper manners (especially in contrast to the misogynistic Phil Spector), but by the time Fear of Music’s lackluster initial mixes came back to the band, Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth had begun to grow weary of his input. Aside from allegations that Eno and David Byrne conspired to re-record Weymouth’s parts on Remain in Light once she was out of the studio, the biggest gripe with Eno was how much credit—specifically financial—he should receive for that album. After the sessions, Eno asked the participants to write their proposed percentage splits on a piece of paper, thinking the averaged numbers would be fair to everyone, and was tremendously insulted by the results. Chris Frantz did not include his proposed percentages, but writes “Brian was lucky we agreed to give him anything.” If you want more Eno, I heartily recommend David Sheppard’s On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno, which is endlessly entertaining and enlightening.

The Heads: Something that goes entirely unmentioned in Remain in Love is Chris Frantz, Tina Weymouth, and Jerry Harrison’s 1996 album No Talking, Just Head as The Heads, a Byrne-free reunion with a variety of guest vocalists ranging from Blondie’s Debbie Harry to Live’s Ed Kowalcyk. (Harrison produced Live’s super-hit Throwing Copper, hope he took the points.) The album’s release and tour were submarined by a lawsuit by David Byrne, but the lead single, “Damage I’ve Done” featuring Concrete Blonde’s Johnette Napolitano, bounced around MTV for a bit. (I revisited it and nope, still not a fan.) When asked about The Heads experience by Rolling Stone, Frantz says that he “didn’t want to write about an experience that was kind of a downer for me in the end,” telling the interviewer that he canceled his RS subscription over their critical review of the album.

David Bowman: The author of the 2001 book This Must Be the Place: The Adventures of Talking Heads in the 20th Century is not mentioned by name, but when Chris Frantz says in the preface that “A number of books have been written about us, but most of them are not very good and none of them have given the reader the true inside story,” the target is clear. Remain in Love refutes several prominent stories from that book.

Adrian Belew: The guitarist whose inventive work elevated Remain in Light and Tom Tom Club’s self-titled debut is mentioned sparingly, but is the subject of one of the biggest changes in narrative. Bowman’s book claims that Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth asked Belew if he would replace David Byrne in Talking Heads, an offer which he politely declined in deference to Byrne. In Remain in Love, Frantz says “We had talked to Adrian about becoming a permanent member of Tom Tom Club as a singer and guitarist. Somehow, this was misinterpreted by Adrian […] he thought we were asking him to replace David in Talking Heads, as if we could do that.” Talking Heads without David Byrne? Who could imagine such a thing?

Tina Weymouth: I have not read David Bowman’s This Must Be the Place, but judging from reviews and this 2003 Salon piece in which Bowman asserts “she really is the Lady Macbeth of rock” (and relays a string of mortifying things she’s said about Byrne), it is not kind to Tina Weymouth. Chris Frantz makes up for that treatment and then some. During Remain in Love, she never says a negative thing to anyone who wasn’t clearly a villain (e.g. Johnny Ramone, Phil Spector). She comes off as a saint, routinely lifted up by his fawning descriptions of her innate beauty, fashion choices, stage presence, and creative impulses. Maybe she is a saint! Maybe that’s how you stay married for over forty years! But it’s a sign of the surface-level engagement in Remain in Love that Weymouth’s personality never fully blossoms. Recalling full conversations is not in Frantz’s repertoire, so he moves from event to event through extractable details, and those details aren’t treated with an analytical eye. Do I get an inside sense of what makes Tina Weymouth a fantastic bass player (and she certainly is!) aside from a natural aptitude for the instrument? No. After reading Peter Hook’s Joy Division and New Order memoirs (I’ll get back to those books in a bit) and Paul Hanley’s The Big Midweek: Life Inside The Fall, I had a greater appreciation for what they did as bassists, and what their fellow musicians were doing. Remain in Love didn’t expand my understanding of how Talking Heads worked, and that’s a disservice to all four members, but especially Weymouth.

Talking Heads audiences: If I learned anything from Chris Frantz going over nearly every Talking Heads concert up until Fear of Music, it’s that there were two different types of Talking Heads audiences in the ’70s: most were immediately and thoroughly in love with the band’s music (“I have no doubt that a certain degree of rapture was achieved by everyone in attendance”), but some required two songs before “we won them over with our energy and attitude.” There was remarkably little struggle to their ascent. The Talkin’ ’Bout the Tour section is a standard for music memoirs, but Frantz focuses on drab details, not shifting dynamics. What did they wear? What did they eat? What hotel did they stay at? How many encores did they get? What notable people did they meet? Reading these details over and over was like consuming a bottomless bowl of bran flakes.

David Byrne: In case I’m coming off as a David Byrne stan, I’ll recap the worst of his offenses discussed in Remain in Love. At RISD, he covertly reorganized an art show (that was ultimately canceled) to put his paintings up front. During the early days of Talking Heads, he made Tina Weymouth audition and re-audition to be the band’s bass player. Once the band started recording and releasing music, he secured the exclusive writing credits for many of their songs. He encouraged the addition of a second bass player for Remain in Light and the subsequent tours, diminishing Weymouth’s role. He mentioned the possibility of the band breaking up or him leaving the band in interviews without discussing it first with the other members. He was impossibly demanding during the Stop Making Sense tour and on the set of True Stories. He damaged a hotel room once. He essentially ghosted the other members after 1988’s Naked and announced that the band was over in a 1991 interview with the Los Angeles Times. He decided to leave his wife after the band’s 2002 Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

All valid criticisms!

I’ve read enough music memoirs and biographies to be prepared for such indiscretions. After Bob Mehr’s Trouble Boys: The True Story of The Replacements and three books on The Fall, I had to reset the bar for bad behavior and dictatorial control to account for The Mats and Mark E. Smith. (I can only laugh at the thought of Chris Frantz joining The Fall and encountering MES’s arbitrary and/or punitive assignment of songwriting credits.) The heavy drug usage and interband infidelity in Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain’s Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk makes those elements seem practically quaint in any other book (respectively, they are minimized and non-existent in Remain in Love). These more extreme examples don’t serve to excuse what David Byrne did, but to explain my constant thought of “There must be something worse coming,” and being surprised when it never did.

It’s not a secret that David Byrne is a strange guy—his off-kilter lyrical perspectives are a big part of Talking Heads’ appeal—and the discussion of his borderline case of Asperger’s syndrome in his 2012 How Music Works book offers some context for that behavior. Neither Byrne nor his bandmates knew about or understood his placement on the autism spectrum during Talking Heads’ run (“Watch out for the autism,” Tina Weymouth is quoted as saying in the 2003 Bowman article, turning the diagnosis into an epithet), but many of Byrne’s quirks make more sense given that context. Before Chris Frantz even met Byrne, he knew of him as an anti-social, heavily bearded guy floating around their RISD dorm. And yet he chose to be in a band with Byrne (The Artistics) and then move to NYC to form a different band with Byrne, while living in a decrepit loft space with both Byrne and Weymouth. The aforementioned indiscretions aside, there’s remarkably little conflict in their relationship, despite living and touring together. (Contrast these accounts with the oil-and-water mix of Blake Schwarzenbach and Chris Bauermeister as documented in Don’t Break Down: A Film about Jawbreaker.) Many of Frantz’s petty jabs target Byrne’s atypical behaviors—on multiple occasions, Frantz insists Byrne’s interest in cybernetics is mere posturing to appear smarter; there’s a judgmental description of Byrne standing by himself at a party, unable or unwilling to socialize, that hits very close to home—often in contrast with the extreme comfort that Frantz and Weymouth found in social situations.

Either in spite of or due to Chris Frantz depicting both himself and Tina Weymouth as largely faultless, eminently social human beings and David Byrne as an inexplicable and sporadically cunning weirdo, I found myself feeling for Byrne. Frantz never wonders how the band’s rapid, ever-escalating success affected someone who was, by Frantz’s own account, simultaneously drawn to and uncomfortable in the spotlight. It’s Frantz’s expectation that Byrne would suddenly change, that he would normalize and process emotions and friendships the same way Frantz and Weymouth did, that baffles me. Weymouth’s prior criticisms that Byrne is “a man incapable of returning friendship” who doesn’t “love” his former bandmates is echoed in several places by Frantz, most notably in a reprovement of Byrne for “the sin of omission” because he was incapable of giving credit or compliments to his bandmates. Did he express his appreciation or fondness in different ways? It’s unclear. It never seemed easy to be Byrne’s artistic collaborator, let alone friend, but Frantz’s rancor often surpasses the described behavior.

Chris Frantz: I’ll step back for a second to discuss a pair of books with a similar gambit. By the time Peter Hook published Unknown Pleasures: Inside Joy Division and Substance: Inside New Order, he was out of New Order on acrimonious terms. By the time I read those books, Hook had toured on the back catalogs of both bands, a decision I had viewed as questionable, if not desperate. It wasn’t that I viewed Hook as an inessential part of either band—his bass lines are their defining musical feature—but it was odd, if not unprecedented, that someone who was (barring a few cuts on Movement) not the singer of the band would go out and sing those songs.

After reading Unknown Pleasures and Substance, I will readily admit that I was wrong. Peter Hook has an equal claim to those bands’ legacies and every right to tour that material. Not only did those books delve into his specific contributions to classic songs (which, in the case of New Order, often went beyond the bass part), he’s a convincing narrator. There’s a “let me tell you about my life while I have a pint at the pub” quality to Hook’s writing that’s steadfastly appealing; to embrace the cliché, you feel like you were there. He’s brutally honest about the band’s faults and especially his own faults. He has plenty of regrets—personal, professional, romantic—and never hesitates to reveal his darkest, least flattering moments. Does he discuss Bernard Sumner’s bad actions during their power struggles? He sure does. But he also establishes why he loved being in a band with Sumner, what unique elements Sumner contributed to those bands, and why he misses their former bond. He paints the whole picture, warts and all.

I thought about Peter Hook’s memoirs often during Chris Frantz’s Remain in Love, initially because of that similar legacy-wrangling gambit. Would I be swayed to Team Frantz? But after I got through the initial section on Frantz’s youth, I kept getting tripped up by the absence of critical self-analysis. There’s no humility to Remain in Love, just a series of big wins. The mistakes and regrets that made Hook approachably human are never mentioned or acknowledged. Frantz discusses his relationship with Andi Shapiro, which lasted at least a year at RISD, but once he saw Tina Weymouth, he was in love with her. Both Frantz and Weymouth were in relationships when Frantz made a late-night visit to Weymouth’s apartment and asked to sleep with her (she politely declined), but Frantz doesn’t remember this action as a questionable move on his part, but an encouraging sign of a future with Weymouth. There’s no acknowledgment of a breakup with Andi—the following school year she’s still with him and sharing a studio space, then he’s suddenly in a relationship with Weymouth—but she’s mentioned a couple of times later in the book as a dear friend. At the very least, it should have prompted an editorial note.

I relayed that part to a friend, who dismissed it as a non-issue: “That’s art school for you.” But for the rest of the book, it made me wonder “What isn’t Chris Frantz mentioning?” Remain in Love has an unspoken focus on the good times—note again the absence of The Heads’ No Talking, Just Head—and at points, that works to its favor. The best chapters are separate from the central conflict: without having to worry about keeping score with David Byrne, he relaxes when talking about Tom Tom Club, Weymouth and his production duties for Happy Mondays and Ziggy Marley, and (for the most part) his appreciation of the B-52s. (He still revels in how disagreements over David Byrne’s production of Mesopotamia led it to be curtailed to a commercially unsuccessful EP.) It’s fair that he’d prefer to bask in the glow of “Genius of Love” than mention Tom Tom Club’s three albums after 1988’s Boom Boom Chi Boom Boom, and even great biographies, like the previously recommended On Some Faraway Beach, spend far more time on beloved records than forgotten ones. But it’s hard not to notice how much Frantz massages both his and Byrne’s resumes to serve his agenda. While Frantz’s greatest successes are heightened, David Byrne’s artistic contributions are minimized (his lyrics are barely mentioned; he dismisses the choreography of Stop Making Sense as a rip-off of theater director Robert Wilson, who Frantz fails to mention would later collaborate with Byrne on The Knee Plays) and his failures are emphasized (schadenfreude abounds when The Catherine Wheel sells a hundredth of Tom Tom Club and when True Stories fizzles at the box office).

There’s only one moment when Frantz discusses a major personal failing and it is absolutely buried in Remain in Love. After a few brief mentions of his cocaine habit following the success of the Tom Tom Club’s first album, a stray paragraph in the penultimate chapter (which is mostly about yachting in the Bahamas and running into famous friends) reveals how Weymouth gave him an ultimatum in 1984 to clean up his act or their marriage was over. To the best of my memory, it’s the only marital strife Frantz recalls, amidst an endless stream of flowery assertions that their love was never stronger than in that current moment. Peter Hook would have dwelled in that moment, sweating over the health of his relationship, but Frantz rushes through it so he can mention encountering Patti Smith dressed in all black on a beach in the Bahamas.

I’m left with an incomplete picture of the author. Chris Frantz seems very nice, and it’s entirely possible that he is. I don’t know! Remain in Love is a book-length version of “My greatest weakness is caring too much.” From the best that I can tell, both Frantz and Tina Weymouth are friendly people and superlative musicians who suffer from an enormous complex regarding their personal and professional relationship with David Byrne. On one hand, I get it. There’s no denying that the rhythm section of Talking Heads was foundational to the band’s success, that Talking Heads would not have been Talking Heads without them. Harboring continued resentment over David Byrne securing sole songwriting credits for many songs and choosing when the band was over is understandable. It was their livelihood too. Seeing Byrne monetize the band’s back catalog with the American Utopia Broadway show while being disinterested in reuniting the band must be frustrating. But Remain in Love is so committed to serving its “Isn’t David Byrne the worst?” agenda that a fundamental conundrum is never addressed. If you hate him so much, why do you want so badly to perform with him again? If his contributions are so overrated, why are they necessary? Frantz concludes Remain in Love by contrasting Byrne’s anti-reunion statement that “it’s time to move on” with his own assertion that “When speaking about my family, my friends, and my band, I am not a person who ‘moves on.’ I remain—and I remain in love.” Maybe that’s commendable loyalty. Or maybe it’s stubbornness, and his unwillingness to move on, to reassess, to change perspectives makes Remain in Love an infuriating book, forever stuck in a grudge.

Talking Heads: Remain in Love certainly didn’t give me a greater appreciation of or affection for the music of Talking Heads, but thankfully, it didn’t spoil my enjoyment either. One of Chris Frantz’s best decisions is talking about their 1980 concert in Rome during the opening chapter, a high point for the band and its expanded, Remain in Light-era lineup. That performance is available in full in YouTube, and rather than suffer through this book, spend your time watching that set. Pull out one of their classic records or put on the Stop Making Sense movie. Their music remains cerebral and physical, challenging and fun, serious and playful, familiar and new. Their interpersonal fissures may never close, but what they achieved together rises above the infighting.

|

Silkworm’s In the West originally came out on CD and cassette on Seattle’s C/Z Records in 1994. I don’t recall specifically when or where I picked up a copy, but I can feel the accumulated grime on my fingertips from flipping through CD bins searching for it, triggering a Pavlovian response to go wash my hands. In the West lingers in that context, the feverish nightmare of its cut-and-paste cover art sharing an early-’90s aesthetic with countless other denizens of those bins, even as its contents far surpassed its now-forgotten neighbors. A quarter century after its initial release, Comedy Minus One honors In the West with its first-ever vinyl pressing, updating elements of its cover art but retaining the unsettling spirit of the original, blackened layer of dust not included.

This half-measure feels appropriate, as In the West deserves to be brought into 2019 but cannot be fully extracted from 1994. “Dated” is typically derogatory, but context is not, and In the West benefits from understanding its place within Silkworm’s development. After working through a series of demo cassettes during their infancy in Missoula, Montana and move to Seattle, Silkworm released their debut album L’ajre in 1992, followed by a string of seven-inch singles and the …His Absence Is a Blessing EP. There are flashes of excellence during those early years, later collected by Matador in the 2CD Even a Blind Chicken Finds a Kernel of Corn Now and Then: ’90–’94, particularly Tim Midyett’s affable “Slipstream,” Andy Cohen’s defiant “Scruffy Tumor,” and Joel R. L. Phelps’s reference-setting cover of The Comsat Angels’ post-punk classic “Our Secret,” but as the compilation’s self-effacing title acknowledges, they hadn’t figured it all out yet. In the West is the first point when their various influences and individual songwriting voices congealed into a whole, a process that would be furthered just eight months later with the release of its follow-up, Libertine (which is also once again on vinyl via CMO) then blown up by Phelps’s departure.

A congested timeline to be sure, but In the West was a significant milestone. Recorded by fellow Missoula native Steve Albini (dutifully uncredited), stylistically it bears far closer resemblance to early ’80s post-punk, like Mission of Burma or the aforementioned Comsat Angels (Waiting for a Miracle, Sleep No More, and accompanying singles only), than most of their contemporaries. I doubt their adopted homebase of Seattle did them any critical favors; In the West had just enough early-’90s scuzz in its guitar tones for unfocused scribes to absentmindedly sort them into the grunge pile, where their songwriting approaches would be decidedly out of place. (Not that critics, then or now, always bother to differentiate who’s singing which songs.)

The most nagging detriment of In the West’s 1994 date stamp has thankfully been corrected: the remix/remaster job for this reissue is a night-and-day difference from its original release, which suffered from era-typical muddiness and a thin mix that shackled drummer Michael Dahlquist’s considerable power. Starting with 1996’s Firewater, Silkworm’s albums carried a reference-quality combination of space, punch, and clarity—exemplars of Albini’s “the sound of a band in a room” engineering ethos—and this update brings In the West in line with those later recordings, which is no minor achievement. In the West is a dramatically different experience with a palpable rhythm section. It officially sounds like a Silkworm album, not a dry run at one.

In the West, then and now, is a uniquely dark album in Silkworm’s catalog, equally explosive and implosive. With the possible exception of its predecessor L’ajre (I’ll take the zero on the homework of revisiting that album), In the West is Silkworm’s heaviest guitar rock record, with Andy Cohen and Joel R. L. Phelps frequently churning thick chord progressions into clouds of noise, a practice that Libertine largely abandons. These storms are dynamically balanced with unsettling lulls, passages where the guitars vanish and minimalism takes over. There are deep-rooted melodies on most songs, but the up-tempo tracks skew more rocking than overtly catchy, with no earworms like Libertine’s “Couldn’t You Wait” or Lifestyle’s “Treat the New Guy Right.”

Typical to Silkworm’s democratic principles, In the West features a nearly even split between the three songwriters, but my reductive take on their respective approaches—Tim Midyett as the introspective, casually funny romantic, Cohen as the black-humored, semi-historical storyteller, Phelps as the nervy font of psychodrama—hasn’t quite settled yet. Midyett’s four songs are caught between Missoula and Seattle, youth and adulthood, with “Garden City Blues” ruminating on the mixed feelings of a return home, rousing from quiet reservations to unencumbered emotions. “Punch Drunk Five” evokes Montana in the final few lines of its hormonal rave-up, while the rocking “Incanduce” flits between staying, going, returning, and running away before being overcome a monstrous, low-slung riff. The most atypical Midyett contribution is the eight-minute “Enough Is Enough,” which gradually arcs from whisper to roar along with its uncomfortable lyrics about a pushy date. There are moments of humor in these songs, most notably the exasperated “Aw Jesus Christ!” in “Punch Drunk Five,” but Midyett’s search for himself and/or someone else tends to be lonely, over-excited, or frustrated, not poised. The stellar “Garden City Blues” is his best song on In the West, in possession of perspective rather than in pursuit of it.

In one sense, the quick synopsis of Andy Cohen’s songwriting applies to his trio of songs here: pitch-black humor coats almost every line (“Go into the woods and live with the bears / That way you can kill someone and nobody cares,” “Then I grabbed a drowning man / I used him for a raft”), loose narratives put Cohen’s voice in violent, unsavory characters, and why yes, that is a reference to General Pershing in “Dust My Broom.” In another sense, they leave you wanting more than the synopsis: Cohen improved dramatically over the next few albums in his ability to imbue potentially unlikeable characters with affecting depth (see Firewater’s trio of “Slow Hands,” “Tarnished Angel,” and “Don’t Make Plans This Friday”). This concern doesn’t matter much for “Dust My Broom” and “Into the Woods,” whose riffs scorch the earth like Sherman’s March to the Sea, but the slow-boiling “Parsons” never leans out of the lyrical darkness and is most compelling during its instrumental bridge.

It’s impossible to overstate the degree to which Joel R. L. Phelps ratchets up the intensity level on In the West; whether quietly repeating a line in a shell-shocked trance or howling loud enough to wake the neighborhood, Phelps commands dramatic tension like few other songwriters. “Raised by Tigers” (which I wrote about more extensively at One Week // One Band) condenses a wartime novella about the younger brother left at home into five masterful minutes. The initially sparse “Dremate” takes heart-on-sleeve to the utmost extreme, turning over the promise “Bare to you my heart” and its myriad ramifications before bursting into flames with the screamed refrain “Say that you will.” The bass-driven post-punk of “Pilot” closes In the West in an intriguing way, given the hair-raising climaxes of Phelps’s other two songs. The lyrics give full warning of what might come—“When I collide it will be something to remember / When I fall from the light it will be something to remember”—but even as Phelps teases a full-out yelp in the final minute, he pulls back, teetering on the precipice of that fall. Instead of the mammoth chords that shook many of the preceding songs, dual leads snake over the bridge, with Phelps’s wordless vocal accompaniment a welcome touch. Phelps excels on In the West at establishing and maintaining this unblinking level of intensity, but an entire album in this headspace would be draining. Phelps’s songs benefit from the shorter, punchier tracks like “Into the West” and “Incanduce” elsewhere on In the West; on Libertine and his solo / Downer Trio records, his wider range of approaches heightens the truly bristling moments.

To my knowledge, there’s no established hierarchy for Silkworm albums, no consensus ranking. You get to Silkworm albums when you get to them, and getting them doesn’t necessarily mean getting them. It took years (and the life experience acquired during those years) for me to fully appreciate Firewater, which finally clicked and became one of my favorite Silkworm records. Ranking them according to a perceived objective sense of quality misses the point: Libertine is a different experience than Firewater, which is a different experience from Developer, and so on, and the greatness of Silkworm comes from the range of those experiences. There are days when Lifestyle is my favorite Silkworm album and days when It’ll Be Cool is my favorite Silkworm album. This reissue puts In the West fully in the conversation. The songs were always there, but that old mix? It was work, a smudged lens distorting artistic intent. Now In the West is on a level playing field, and I understand its experience in a way that I hadn’t previously. It’s a darker, heavier experience than its brethren, and there will be days when that experience fits and days when it doesn’t. But 25 years after its release, and probably 20 after I first heard it, I get In the West. Maybe there’s still hope for L’ajre.

A valuable postscript: Almost two hours of bonus material is included in the digital download for In the West, and while little of it qualifies as essential listening for people who don’t self-identify as Silkworm devotees, that tag absolutely fits me and my appetite for ephemera, demos, and live recordings. Phelps’ rendition of the Christina Rossetti-penned Christmas carol “In the Bleak Midwinter” and Midyett’s yearning, “UK Surf”-esque alternate take on “Incanduce” (Dahlquist wrote on Silkworm’s web site “I think we tried to play quiet to mock some asswipe club owner, played ‘Incanduce’ in this sort of American Music Club way, and liked it enough to record it”) originally appeared on seven-inches and then Even a Blind Chicken, so they are both the best and most familiar tracks included here. (“Midwinter” is a precursor to Phelps’ more recent contributions to Comedy Minus One head Jon Solomon’s WPRB Xmas marathons, a few of which are available here.) There’s a raucous live rendition of The Dream Syndicate’s “Halloween.” Five songs are represented via seven direct-to-DAT demo recordings from 1991, including a pair of hyperspeed run-throughs of “Dust My Broom.” There are six individual live songs and a full 1993 set from Chicago’s venerable Lounge Ax, and the performances resonate through the mixed recording quality.

|

The recent vinyl reissue of Shiner’s mammoth Lula Divinia was a welcome marker of my twentieth year of listening to Allen Epley’s music. Whereas many other musicians in my circa-1997 heavy rotation have either lost my interest or lost their commitment, Epley has been a model of creative consistency with Shiner and The Life and Times. Lineups have shifted, aesthetics have evolved from Midwestern math-rock to sinewy shoegaze, yet the touchstones of Epley’s craft remain resolute: strong vocal melodies, often tinged with melancholy; slyly complex arrangements punctuated with immensely satisfying riffs; and a rhythm section with its own gravitational pull.

With their fifth, eponymous LP, The Life and Times has surpassed its primary predecessor in both duration and output. After switching rhythm sections for 2005’s debut LP Suburban Hymns, the trio of Epley, bassist Eric Abert (Ring, Cicada), and drummer Chris Metcalf (The Stella Link) has remained stable (aside from a brief dalliance with Traindodge’s Rob Smith) and has their approach locked down. Records lean in different directions—the shoegaze sonics of 2006’s The Magician EP, the cinematic scope of 2009’s Tragic Boogie, the brass-tacks immediacy of 2012’s No One Loves You Like I Do, the melodic surges of 2014’s Lost Bees—but each fits firmly within the group’s catalog as a whole. Both last year’s all-covers Doppelgänger EP (worth the download) and this self-titled LP operate in a middle ground of these leanings, assured of their stylistic parameters.

Reliability doesn’t make for a particularly sexy narrative—“Excellent Band Continues to Be Excellent”—but the songwriting on The Life and Times earns the group another long-term residence in the aforementioned heavy-rotation pile. Its bookends are the album’s longest and strongest tracks, each mining a familiar Epley lyrical motif: “Killing Queens” explores the thin line between adoration and obsession with falsetto verses and a roaring, slide-enabled chorus riff, while “We Know” sees midlife ennui haunted by creeping dread, as spaced-out chimes give way to Chris Metcalf’s pummeling outro. “Dear Linda” emerges from its shoegaze cocoon to find bracing clarity via the rhythm section. The colossal bridge riff of “Group Think” recalls Shiner’s finest moment, the ascendant mid-song interplay of “The Situationist.” “Out Thru the In Door” splits the difference between slippery post-punk verses and a sing-along chorus worthy of the Zeppelin smirk in its title. Abert leads the practically dance-ready “T=D/S,” his bass flipping between notes before opening up in the swirling chorus. The alternately dreamy and anthemic “I Am the Wedding Cake” undercuts its romantic overtures with a striking inclusion of “I don’t know you” in the chorus. Only the languid breather “Falling Awake” fails to leave much of an impression, but it does clear the deck for the pulsing instrumental “Dark Mavis.” Nine songs in a tight forty-one minutes, with each song inhabiting its logical residence in the running order.

It would honestly be easier if The Life and Times had a dramatic narrative, if Allen Epley became a hermit after The Egg and reappeared sixteen years later with a long-overdue reminder of what made his music compelling in the first place. But I’ll take the commitment to a regular release schedule and to the road, I’ll take the stack of worthy releases that have maintained my interest in that span. Whether The Life and Times sifts out as the finest in their catalog is up for debate—it’s certainly in the running—but the best thing about the group’s discography is that convincing cases can be made for virtually all of their albums.

|

My most anticipated album for ten years running has arrived.

I first heard demos for Atoms and Void’s And Nothing Else sometime in 2005, back when the group was called Ghost Wars and debuting new material on MySpace was normal. To say the project intrigued me is a vast understatement: this collaboration between former Juno singer/guitarist Arlie Carstens and longtime Damien Jurado cohort Eric Fisher faced the immense task of following up my favorite album, Juno’s 2001 opus A Future Lived in Past Tense (which may get an overdue vinyl reissue in the near future). Those initial demos offered a range of possibilities: the IV-drip blues duet “Destroyed, The Sword of Saint Michael,” the alternately plaintive and thunderous post-rock of “Waves of Blood,” and the gentle humanism of the half-instrumental “Lay Down Your Weapons.” Less Dischord and DeSoto, more Kranky and Temporary Residence Limited. The distance from Juno’s dynamic post-punk was evident in these recordings, but even greater in the process, which abandoned Juno’s five-member line-up in favor of a long list of guest musicians steered by Carstens and Fisher, inspired by the legendary sessions for Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock. No, this record would not be a simple sequel to the life-affirming expanse of A Future Lived in Past Tense, but its potential as a spiritual heir was evident from that handful of songs.

No one could have predicted that this potential would take a decade to realize. Dual catastrophes derailed completion of the demos: Eric Fisher’s laptop was stolen in 2006 and the back-up hard drive storing the ProTools sessions was corrupted, leaving the group with only .mp3 mix-downs of the sessions. Repeating the recording process was not an option: reassembling the geographically scattered array of guest musicians would have been a logistical impossibility. Years passed while Carstens and Fisher wrangled with data-recovery services in ultimately futile attempts to reconstruct session architecture. Enthusiasm for the material remained, but momentum was constantly undercut by all-too-familiar varieties of major life events: family illnesses, friends passing away, exhausting new jobs, constant travel. Every few years I’d hear a tantalizing new demo or receive an encouraging progress report, reinforcing my belief that at some point, the album would come out, but seemingly every hurdle was thrown at Carstens and Fisher, even the theft of the group’s original name by a litigious electronic artist.

Despite fate’s cruel, repeated intervention, And Nothing Else finally exists, released digitally in September (on my birthday, no less). Even “The Architect and the Atomizer” offers a red herring of hair-raising guitar rock. After a moody rise and fall laced with strings and piano, Carstens’s checked delivery ignites into a final-minute fire-and-brimstone sermon. Lyrics like “Three years of reprieve / Does not erase a lifetime of grief / Living on your knees / When the water closes there’s nothing left to see / There’ll be no legacy” recall the get-your-shit-together ferocity of “The French Letter” and “You Are the Beautiful Conductor of this Orchestra,” but it’s the only time Carstens assumes that voice on And Nothing Else.

“Lay Down Your Weapons” hits the reset button on listener expectations for the rest of the album, both sonically and lyrically. It resides in the Talk Talk / Bark Psychosis school of post-rock, with carefully arranged piano, an expressive bass line, and subtle electronic surges supplanting distorted guitars in the instrumental palette. It, too, has a Juno throwback, with its opening lines (“Your son / Wanted to talk a nap / So we closed his casket / And tried not to look back”) echoing similar tragedy in “When I Was In ____” (“Your son’s hands stayed warm / Long after he died”). Its previously instrumental second half now completes that sentiment, with multi-tracked vocals urging to “Lay down your weapons / And lay this love to rest / The wanting, the waiting / Will not take you there.” Whereas A Future Lived in Past Tense called for action, “Lay Down Your Weapons” fittingly recognizes that some circumstances are outside of our control, and no amount of struggling or reaching will bring proper closure.

What’s left, then, is mostly quiet contemplation. The lilting “Feathers From a Bird” floats on piano and clarinet, and its brand of ambient classical fits nicely into a growing prominence of that style. “Waves of Blood” continues the instrumental trend but increases the volume with its merger of Mogwai guitars and the double-drummer approach of Fugazi’s The Argument, manned here by Eric Akre of Treepeople/Built to Spill/Juno and J. Clark of Pretty Girls Make Graves. The crashes help raise the album’s heart rate, but the pairing of melancholy guitar and Rhodes melodies highlights the song. “For Sharon, With Love” is the first of the album’s piano ballads, an elegy (“We tried to walk in the light / But we died in the dark”) whose loneliness is embodied in the noticeable action from the keys. Given its somber surroundings, the brightness of “Golden Shivers,” a pulsing Phillip Glass / Steve Reich homage, is quite welcome. “Destroyed” adds a few overdubs to its demo version, but its skeletal feel remains, leaving nothing in the way of its haunting, mythic rumination on guilt. (Trivia: The closest Atoms and Void came to a live performance was Carstens singing a few bars of “Destroyed” during the soundcheck for Juno’s 2006 reunion shows in Seattle.)

The album’s centerpiece is “Virginia Long Exhale,” a song unveiled in 2005 and updated with a near-finished version two years later. It starts out simply enough—“We go down / To the lake”—and dodges instrumental tension with its careful blend of clarinet, bass clarinet, saxophone, Rhodes, and both acoustic and electric guitars. (Drums occasionally appear, but if quizzed on their presence, I would have likely answered incorrectly.) But Carstens breathes devastating emotion in both hushed baritone and expressive falsetto into the song’s water imagery, rotating through a number of possible connotations—childhood games, baptism, suicide—before settling on the image of a body slowly passing away. In the midst of paralyzing grief, we rely on ritual (“This is what we do / When we know / Not what / To do”) to guide loved ones and eventually ourselves to the end. “Virginia Long Exhale” is supremely sad, supremely beautiful.

Whereas “Virginia Long Exhale” lingers in funereal repose, Eric Fisher’s “The Earth Countered” follows with a nervous energy. Layers of wordless humming, flickering acoustic strums, and distant drumming support Fisher’s lone lead vocal turn on And Nothing Else, but the most unsettling element of the song is the eerie calm with which he delivers “You won’t feel a thing.” After single-minute “Lowercase Blues” clears the decks, Carstens’ atmospheric piano ballad “The Conductor” has room to resonate. It’s not as focused lyrically as “Weapons” or “Virginia,” but there’s luxuriant depth to the arrangement, with woodwinds, Jenna Conrad's backing vocals, and echoing guitar softening each piano chord.

And Nothing Else closes with “This Departing Landscape,” which initially continues the trend of near-whispered Arlie Carstens piano ballads. Its scant few lines—“Things go wrong / The light will fade / The dawn will come / And this too shall fade away / But oh, oh, oh / I wish you could have stayed”—encapsulate the album’s themes of loss, renewal, and regret, but the gradual, determined swell of bob-and-weave guitar patterns and ringing piano chords offers a sense of closure and optimism that didn’t seem possible back on “The Architect and the Atomizer.” And Nothing Else is a heavy, often tragic record, but thanks to “This Departing Landscape,” I don’t leave it dwelling on tragedy or guilt, but rather with the feeling that those weights have been lifted.

And Nothing Else is a deeply personal record, both for Atoms and Void and my own listening history, but its translation of specific experiences into emotional connections is exemplary. “This Departing Landscape” generalizes those experiences into “things,” and given the long-term perspective of the album’s decade in development, I transpose write my own narrative from that era into the album. My father succumbing to cancer, my grandmother passing away at 100, my daughter being born. There’s no answer to the easiest question about And Nothing Else—“Was it worth the wait?”—because its excellence is fused to those events in my memory. Yet few albums can carry such a load (Juno’s A Future Lived in Past Tense foremost among them), a point that’s been underlined hundreds of times in the last decade with each album that didn’t measure up to the hypothetical Atoms and Void album I would one day hear, to the tangible Atoms and Void album that now exists. Perhaps one day there will be another Atoms and Void album (there is more material, like the cut-loose rocker “The Elephant in Your Womb”), a vastly different record that would speak to vastly different experiences, but I’ll apply the patience learned since the initial Ghost Wars demos to any potential timetable.

|

The past year and a half has been generous to Unwound devotees. Between the excellent Live Leaves (a document of their five-person tour line-up for the Leaves Turn Inside You originally intended for release in 2003), Numero Group’s Record Store Day 2013 delivery of Justin Trosper and Vern Rumsey’s high-school band Giant Henry’s unreleased album Big Baby, and Numero’s comprehensive, immaculately designed box set of Unwound’s early days, The Kid Is Gone (the start of a must-own series of reissues, continuing in March with Rat Conspiracy), there’s an embarrassment of riches. Hell, you can even buy t-shirts again. What’s lacking from this steady stream of legacy protection is an actual reunion. No tour dates, no new material, as per the Fugazi model.

If you can accept that Unwound won’t be reforming to unleash Leaves Turn Inside Two or hitting your local club to doubled ticket prices, you’re in a good place to hear Justin Trosper and Brandt Sandeno’s new group, Survival Knife. Like any number of second-acts from 1990s staples (Burning Airlines, Jets to Brazil, Evens, and especially Hot Snakes), Survival Knife faces an inevitable, somewhat unfair comparison to their beloved predecessor, one I’ll dive into instead of attempting to avoid. The four available tracks from Survival Knife recall compact rockers from Repetition and Challenge for a Civilized Society (“Corpse Pose,” “Data”) with some of the mechanical precision stripped away. The hard-rock/hardcore directness infused in Survival Knife’s shout-along choruses was absent from much of Unwound’s art-damaged catalog, particularly the sprawling Leaves. And yet Trosper’s musical DNA hasn’t been completely altered; the mutating guitar parts and verse vocal delivery are immediately identifiable as his work.

If you’re forced to choose between the two seven-inch singles Survival Knife issued in 2013— “Traces of Me” b/w “Name That Tune” on Sub Pop; “Divine Mob” b/w “Snakebit” on Kill Rock Stars—pick up the latter. The Sub Pop single is worth checking out if not faced with an unlikely hypothetical situation (two Unwound fanatics come across one copy of each single at precisely the same time…), but “Traces of Me” feels unduly restrained when compared to the abrasive energy and bigger riffs of “Divine Mob” and the Meg Cunningham-howler “Snakebit.” I prefer Survival Knife when it’s held to my throat.

|

Unlike some of their similarly reformed ’90s indie rock peers, Girls Against Boys (the unfamiliar should consult my primer) aren’t returning from the hard stop of an acrimonious break-up. Their decade of relative inactivity since the Jade Tree–issued You Can’t Fight What You Can’t See was still marked by the occasional live appearance—specifically, the Touch and Go 25th Anniversary Block Party, All Tomorrow’s Parties’ Don’t Look Back, ATP vs. Pitchfork, and a 2009 European tour; generally speaking, anywhere I was not living at the time. Their 3X bass expansion unit could still boot up when called upon, but as a fully functioning machine, GVSB had gone into standby. I’d have to subsist on their consistently excellent discography, particularly their trio of superlative LPs on Touch and Go, and cross my fingers that one of these appearances would be in my time zone.

Three surprises greeted me in 2013: first, Girls Against Boys announced a brief East Coast tour, including a stop at Great Scott in Allston; second, a pairing forged at the Absolutely Free Festival in Belgium made its way to the American bills as well, with The Jesus Lizard’s David Yow accompanying GVSB for part of their set; third, The Ghost List EP was announced for a fall release on Epitonic. Of the three, new material was the stunner. (David Yow keeping it in his pants was a close second.) It’s one thing to issue an EP after a decade of heavy touring, but with only sporadic events on their calendar, Girls Against Boys weren’t the likeliest candidates to present new songs.

Not that I’m arguing with this development. Similar to Superchunk’s post-hiatus records, Girls Against Boys slip comfortably back into their trademark sound on The Ghost List. Its five tracks occupy terrain between the well-oiled machinery of House of GVSB and the up-front melodies of You Can’t Fight…, constructing a veritable bridge over the questionable production values of Freak*on*ica. Despite being assembled from a mix of half-finished song sketches and newly authored tracks, The Ghost List doesn’t prompt a round of when-was-this-song-written like My Bloody Valentine’s M B V.

With only five songs spanning eighteen minutes, The Ghost List wisely avoids filler. Opener “It's a Diamond Life” struts with distorted keyboards and emphatic Eli Janney background vocals while Scott McCloud glares at both one-percenters (“It's a crystal system”) and those overeager to join them (“I don't know what I want / But I want it a lot”). “Fade Out” accelerates from trot to gallop on its chorus, flying by in a scant 2:20. The subtly meta-critical “60 > 15” ("I've heard your volume kills / I’ve seen your psychic thrills") confirms GVSB's rhythm section's continued ownership over mid-tempo pummeling. Despite GVSB’s ongoing emphasis on rhythm, “Let's Get Killed” offers one of their clearest melodies to date, on par with the highlights of You Can't Fight... and “One Dose of Truth” from the Series 7 soundtrack. Finally, “Kick” recalls the genuine malice lurking on Girls Against Boys' mid-period classics. Its orchestral stabs are a successful new addition to their repertoire, even though the EP’s emphasis on trademark-renewal didn’t mandate a step forward.