|

There was no shortage of excellent music released in 2020, a fortunate development given the (cough) lack of other options for my entertainment budget. I have written about my top 25 records of the year over here and provided sample songs from Bandcamp (and YouTube when necessary). No, seriously, click the link and then head back here. Here’s a large image directing you to it. You could, nay, should click on that.

There’s an emphasis on physical media in the layout of that list, which involved photographing the labels of each album and moving my desk so that I could take a proper picture of the 25 covers on my shelf. I understand that not everyone has the same fondness for buying buried under piles of vinyl records that I do, but all of those albums are available to purchase digitally as well. No one needs a lecture about the importance of supporting artists, particularly now, so I will spare you the pontification.

I could have easily gone past 25 selections, but the display limitations of my five-by-five Kallax shelf kept the number reasonable. Hopefully you know some of them and check out a few others. If you are interested in further listening, great, here are ten-ish honorable mentions that I wholeheartedly endorse.

Beauty Pill / Please Advise: Starting off the year with an overdue pressing of their Sorry You’re Here soundtrack, Beauty Pill raised the bar with the Please Advise EP, adding two fantastic new songs (“Pardon Our Dust” and “The Damndest Thing”), a revelatory cover of The Pretenders’ “Tattooed Love Boys,” a reworking of “Prison Song” from their overlooked 2004 LP The Unsustainable Lifestyle, and a remix varying format to their ever-impressive catalog. Standalone single “Instant Night” should not be missed.

The Casket Lottery / Short Songs for End Times: The Kansas City band continues to skirt the line between emo and post-hardcore. Rolling over half their line-up revitalized the songwriting, and a dedication to putting the guitars first didn’t hurt Nathan Ellis’s big vocal melodies. I’ll take dynamic tracks like “Sisyphus Blues” and “Unalone” over virtually anything else from the last decade of the seventeenth wave of emo.

Coriky / Coriky: Ian MacKaye, Joe Lally, and Amy Farina could have easily kept their latest collaboration to themselves, savoring the joy of their musical chemistry during closed-off practice sessions in the basement. Thankfully they did not, and Coriky relays that honed spontaneity with songs that speak to the moment but avoid being limited by it.

Guided by Voices / Surrender Your Poppy Field & Mirrored Aztec & Styles We Paid For: Robert Pollard’s revitalized band delivers another three albums in 2020, all worthy additions to his towering discography. Each has immediate highlights, stockpiles of riffs and lyrical turns of phrase that the band miraculously hadn’t used yet, and at most one song that starts off as an irritant and eventually grows into a favorite.

Erik Hall / Music for 18 Musicians: Seventeen performers short, Erik Hall records Steve Reich’s classic composition on his own, giving it a very particular signature. Is it more personal? More approachable? Slightly softer? All three? Whatever the case, it’s a welcome addition to the other performances of Music for 18 Musicians in my collection, and demonstrates how such a specific, interlocking piece of work can nevertheless be quite flexible.

Rafael Anton Irisarri / Perepeteia: I dove into Irisarri’s catalog past this year, and while I very much enjoyed the brain-wiping alien landscapes of Perepeteia, I found myself returning to 2019’s Solastagia, 2015’s A Fragile Geography, and 2010’s The North Bend more often. Cursed by his own success!

Savak / Rotting Teeth in the Horse’s Mouth: Savak simply won’t stop releasing excellent music, supplementing their consistently rewarding fourth LP since 2016 with a just-as-necessary seven-inch and a lathe-cut eight-inch. It’s a simple relationship: they put records up to order, I buy them.

Shell of a Shell / Away Team: Pile guitarist Chappy Hull fronts the Nashville quartet Shell of a Shell, whose brand of guitar rock flirts with anthemic melodies on “Knock” and “Away Team,” but cannot deny their deep-rooted desire to bring chaotic strains of noise to the mix. Closing track “Seems Like” embraces the cacophony as it spirals out.

Silver Scrolls / Music for Walks: Dave Brylawski and Brian Quast of Polvo—would you like me to tell you about Polvo—team up as Silver Scrolls, which picks up where Brylawski’s superb songs on Siberia left off. There’s an easygoing charm to the measured gait of Music for Walks, but complexity bubbles under its surface.

Windy & Carl / Allegiance & Conviction: The welcome return of Dearborn’s ambient dream-pop duo, Allegiance & Conviction puts slightly more emphasis on Windy Weber’s vocals as she spins a loose spy narrative over Carl Hultgren’s ever-drifting guitars. Pour one out for the closing of their beloved Stormy Records.

|

Roughly twenty-five years ago I taped a song off the radio, rewound endlessly to replay it, and then made it my mission to buy a copy of the CD during a high-school trip to Boston. I begrudgingly paid the outrageous sum of $17.99 for a copy of Hum’s You’d Prefer an Astronaut at the Tower Records in Harvard Square—it was out of stock at the nearby Newbury Comics—and, not yet owning a portable CD player, waited anxiously to get home so I could hear the rest of the album.

Over the next days, months, and years, I more than made up for that excruciating delay. I dubbed the CD to one side of a blank cassette and ground its fidelity to mush as I transported myself out of myriad high-school bus rides. The appeal of the introductory single “Stars” was twofold: its massive riffs were bracingly huge, bolstered by a steady undercurrent of compelling textures and melodic leads, but Matt Talbott’s vocals and lyrics eschewed the posturing attitude commonly associated with “heavy” music. The head-fake intro (memorably skewered by Butt-Head: “It sucked but at least it was short”) was quiet and thoughtful, and those qualities remained once the song fully kicked in. The rest of You’d Prefer an Astronaut spiraled out from this combination of overflowing guitars and ponderous, evocative lyrics. Its romantic notions were filtered through stargazing or space-bound narratives, and the album’s lingering threat is becoming untethered, both in literal and relational senses. Hum proved equally adept at meditative mid-tempos (the enveloping drone of “Little Dipper,” the psychedelic imagery and polychromatic tones of “Suicide Machine”), surging rockers (the dark intensity of “The Pod,” the soaring arcs of “I’d Like Your Hair Long”), and ambling odes (“Songs of Farewell and Departure”). You’d Prefer an Astronaut offered familiarity and escape.

You’d Prefer an Astronaut felt like a self-contained world, but after going online and finding their web page (http://www.prairienet.org/~hum/, flaunting a sub-directory and a tilde), I worked my way to Urbana, Illinois' Parasol Mail Order, which offered their earlier records, their t-shirts, related bands, and aesthetically similar bands. I learned how the band went through numerous personnel changes before recording its 1991 debut, Fillet Show, whose groaning pun of a title is an accurate indicator of its contents’ (cough) rather considerable room for growth. After guitarist Balthazar de Lay left to front his own band, Mother (later renamed Menthol), Hum finalized its lineup by adding the youthful Tim Lash on guitar and comparative veteran Jeff Dimpsey on bass (he’d previously played guitar in Champaign-Urbana mainstays the Poster Children and Hum’s brother band, Honcho Overload, alongside bassist Matt Talbott). Thanks to these new additions, 1993’s Electra 2000 was a significant step forward, worthy of being dubbed to the opposite side of my You’d Prefer an Astronaut cassette. Electra is a dynamic, bruising album, driven by the chugging riffs of highlights “Iron Clad Lou,” “Sundress,” and “Winder.” It’s jarring to work backwards to Talbott’s throat-shredding desperation, that approach having been whittled down to a single scream on You’d Prefer an Astronaut’s “The Pod,” and even on its best tracks, Electra 2000’s tonal palette is monochromatic. However raw and comparatively unpolished it may be, Electra 2000 still holds up, especially “Diffuse,” a compilation track added to the 1997 Martians Go Home! CD pressing.

The other breadcrumbs I followed proved that Hum did not exist in a vacuum, that You’d Prefer an Astronaut did not materialize out of thin air. Matt Talbott’s list of his favorite records on Hum’s page (from memory, a cross-selection of turn-of-the-decade indie/alternative guitar rock: Dinosaur Jr.’s Bug, The Flaming Lips’ In a Priest Driven Ambulance, My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, and half a dozen others I’m less certain of, like Mercury Rev, Swervedriver, and Bitch Magnet) traced one side of their development, and the sonic similarities and shared members of various notable bands from Champaign-Urbana and other significant Midwest college towns tracked another. A communal affinity for thick guitar sounds could be found on Poster Children’s Daisychain Reaction (their lone album featuring Jeff Dimpsey and arguably their heaviest), Honcho Overload’s Pour Another Drink, Zoom’s self-titled debut (Matt Talbott is referenced by name on the jittery “Ephedrine Breakfast” from the band’s second LP, Helium Octipede), and Love Cup’s Greefus Groinks and Sheet (an album still discussed in hushed reverence by people who were there, and also me, who was not). Hum’s evolution from Fillet Show to Electra 2000 makes more sense when contextualized within a regional Midwestern sound. And if You’d Prefer an Astronaut used a major-label recording budget to realize a sound previously out of reach to the group, it’s noteworthy to Talbott’s list of favorites that Flaming Lips producer Keith Cleversley was at the helm.

Hum may have existed within a community of like-minds, but my high school provided no such comforts. No one in my social circle had any interest in going deeper into the alternative / indie waters, so band mailing lists and IRC channels were godsends. The members of Hum did not frequent the band’s semi-official listserv (leaving such future-signaling fan/band interactions to the Poster Children) or #hum (back when hashtags were associated with IRC channels), but I found plenty of great people in similar situations. Like a half-dozen others, I did my service by running a Hum fan site, collecting lyrics, photos, and links to supplement Hum’s skeletal web presence.

Hum’s next album, Downward Is Heavenward, didn’t come out until early 1998. Their perfectionist tendencies took precedence over striking while the iron was hot, and Downward was reportedly recorded twice: first with YPAA producer Keith Cleversley, then with Mark Rubel in Champaign. My previews came from the early demo of “Ms. Lazarus” on the CD5 for “The Pod” (a warm, unfussy run-through of an endlessly endearing track) and a third- or fourth-generation cassette of a live show featuring an embryonic version of “Comin’ Home” (not specifically this one, but here's another 1995 performance of it) which sounded far rawer in its infancy (and/or compromised fidelity) and offered an entirely different chorus (“I’ll treat you like a sound,” which I heard for years as “I’ll treat you like a son”). As the release date approached, fan sites got to post 30-second samples of songs—either in the streamable muck of the briefly in-vogue RealAudio format or the comparative clarity of the nascent, bandwidth-punishing mp3 format—and I obsessed over too-short tastes of “Dreamboat” and “Green to Me.” I ordered the vinyl from Parasol because it was coming out at least a week before the CD hit stores, and patiently waited for it to arrive.

Hearing Downward Is Heavenward for the first time was vastly different from my initial spin of You’d Prefer an Astronaut; I had expectations, I’d heard plenty of other excellent bands and records in the intervening years, and my listen was tempered by the group-think of an internet community. I loved it, but my appreciation wasn’t unqualified. The production sheen felt too glossy in comparison to the mid-fi warmth of You’d Prefer an Astronaut. Not every song clicked immediately (looking at you, “The Scientists”). My hopes for a blistering “Comin’ Home” and an enveloping, intimate “Ms. Lazarus”—what I’d already heard, essentially—were dashed. Those hints of resistance, of grasping onto how much my decaying cassette dub of You’d Prefer an Astronaut meant to my bus rides, were on me, not the band. Eventually I got over it with the help of an eardrum-punishing performance at Irving Plaza in New York City (during my moronic phase of being Too Cool for Earplugs), and I could appreciate Downward Is Heavenward for being different from You’d Prefer an Astronaut. The depth of “Isle of the Cheetah” was like a time-lapse video of organic life taking hold of an abandoned structure. “Ms. Lazarus” needed the extra oomph to fully surge in its final section. “Afternoon with the Axolotls” (though lacking its superlative live intro) was thoughtful and explorative. The double-punch of romance and riffs provided by “Dreamboat” and “The Inuit Promise” made me long for the chance to meet new people I might actually connect with. The deftly recorded reverb of “Apollo” made its ache that much more powerful.

Downward Is Heavenward didn’t come close to replicating the commercial success of You’d Prefer an Astronaut. The sci-fi video for lead single “Comin’ Home” was rejected by MTV’s 12 Angry Viewers, one of the network’s shows designed to combat the (accurate) criticism that it aired a diminishing selection of music videos, and second single “Green to Me” gained no traction. The tides were against them: “alternative rock” skewed more and more “pop” (big singles that year included Semisonic’s “Closing Time,” Barenaked Ladies’ “One Week,” and The Offspring’s “Pretty Fly [For a White Guy]”); nu-metal was on the rise with the multiple-platinum success of Korn’s Follow the Leader; and Total Request Live pushed the most popular videos to even greater ubiquity. Meanwhile, Hum’s van was wrecked during a June tour through Canada, forcing the cancellation of most of the remaining dates. The band sounded exhausted in interviews, fully aware of the writing on the wall.

Hum never released an official statement about breaking up or going on hiatus, but after only playing one show in 1999 and two in 2000, they entered cryo-sleep following an opening slot for The Flaming Lips’ New Year’s Eve show at the Metro in Chicago. The members went their separate ways: Matt Talbott formed Centaur with Castor bassist Derek Niedringhaus and drummer Jim Kelly; Tim Lash started Glifted with Love Cup’s T.J. Harrison; Jeff Dimpsey revived the whispered-about Champaign group National Skyline with Castor’s Jeff Garber; and Bryan St. Pere moved to Indiana for a pharmaceutical job. Centaur and Glifted bifurcated Hum’s DNA for their respective 2002 albums. Centaur’s In Streams took a mournful approach to Hum’s foundations, repeating its big riffs over Matt Talbott’s reserved vocals. (I saw Centaur a number of times, but their curtailed opening set for Shiner in St. Louis is seared into my brain, specifically Talbott sighing “Our band is in this [malfunctioning] pedal” while nursing a comically huge bottle of beer.) Glifted’s Under and In emptied a warehouse of head-spinning metallic shoegaze riffs, with the surprising addition of falsetto vocal hooks on some songs. But each band possessed what the other lacked: Centaur needed Tim Lash’s inventive guitar parts to break the repetition, while Glifted needed Matt Talbott’s emotional resonance and structural support to channel great parts into great songs. Dimpsey’s National Skyline was the best of these projects, particularly their 2000 self-titled EP and 2001’s This = Everything, which simultaneously looked back to U2’s The Unforgettable Fire and ahead to the icy, electronic-bolstered post-emo of groups like Antarctica. But Dimpsey never toured with National Skyline, and that group, too, went on hiatus during Garber’s move to Los Angeles to join Failure’s Ken Andrews in Year of the Rabbit (and later form The Joy Circuit). A second wave of projects appeared in the late ’00s, with Tim Lash forming Balisong and Alpha Mile (no studio recordings, but live footage exists for the latter) and Jeff Dimpsey teaming with Absinthe Blind’s Adam Fein for Gazelle, releasing Sunblown in 2008.

Even in ostensible hiatus, Hum still emerged every few years. Furnace Fest called their asking-price bluff in 2003, and their headlining set was preceded by a local warm-up in Champaign. Sporadic regional dates occurred in 2005 and 2008–2009 (I saw their New Year’s Day show in Chicago), picking up in 2011 around the time of the FunFunFun Festival. Two unreleased songs—“Inklings” and “Cloud City”—frequented their sets at these shows, and I attempted to will a seven-inch with studio recordings into existence. A co-headlining tour with Failure in 2015 marked the most significant action since the release of Downward Is Heavenward. Bryan St. Pere opted out of this tour, aptly replaced by Shiner’s Jason Gerkin, and a year later, the band confirmed that they were working on new material. The still-unreleased “Voyager 1” started appearing in 2016. When I saw them (with St. Pere back in the band) in St. Louis in early 2018 (sharing a bill with a reunited Castor!), they unveiled a few new-new songs: “Folding,” “The Summoning,” and an instrumental version of “In the Den,” none of which felt fully formed yet.

The idea of Hum releasing new material was always within the realm of possibility, but turning that promise into actuality was a harder proposition to grasp. Given that Matt Talbott owns and operates his own studio (Earth Analog in Tolono, IL, formerly known as Great Western Record Recorders), the logistics for recording were mostly handled. But the band’s timetable-tipping perfectionism made any hypothetical release date seem impossibly optimistic. Said trait dates back to both of their RCA albums, but resurfaced more recently with regards to vinyl reissues. Talbott was understandably miffed at ShopRadioCast having snaked the reissue rights for You’d Prefer an Astronaut in 2013 and not involving the band in the (assuredly CD-sourced, decidedly shitty) pressing. So the 2LP reissue of Downward is Heavenward opted against a cash-grab rush-job and for an extraordinarily patient, results-oriented process. After years of rejected test pressings and other delays, it finally came out in 2018 on Talbott’s own Earth Analog Records (the second pressing on blue vinyl appears to still be available), and was worth every penny. Whereas the original pressing crammed too much music onto a single LP, the reissue gave the songs room to breathe, and the new mastering job added depth and clarity. Adding “Puppets,” “Aphids,” and “Boy with Stick” as bonus tracks on the fourth side was greatly appreciated. The end result was worth the wait, but it didn’t exactly give hope that the new Hum album would appear anytime soon, even with rumblings that “it’s done except for a few vocals.” An added wrinkle came with the news that Talbott was working on a solo album to complement his living room tours (remember touring?), an album that might somehow come out before the Hum record. Early versions of “Sinister Webs” and the sprawling drone “Way Up Here” popped up on Bandcamp, giving the project the proof of life.

And then that mythic new Hum album just… appeared. Inlet was surprise-released on June 23, 2020 on Bandcamp and presumably also lesser digital outlets, and the Earth Analog–pressed vinyl was available for preorder through Polyvinyl (a wise choice after the early blink-and-you-missed-it drops of the Downward Is Heavenward reissue brought both Talbott and eager fans much consternation). It was a blinding ray of sunlight amidst the endless drudgery of quarantine life, a bona fide event to make up for the fact that calendars had been wiped clear for months. Texts were sent and received as I carved time out of my child-watching schedule to actually listen to the album. Around that time the chatter switched from “whoa there’s a new Hum album” to “whoa the new Hum album is great.”

And it is great.

Inlet’s surprise drop reversed my expectations-burdened introduction to Downward Is Heavenward. Even with the knowledge that Inlet would arrive at some point, the twenty-two years of distance from Downward and all of the offshoot projects—satisfying, underwhelming, and forgotten alike—wiped the slate clean for both this fan and the band. I wasn’t paralyzed by comparing subjective quality, while Hum weren’t boxed in for their next moves. I’ve seen a few people assert that Inlet could have easily come out a year or two after Downward and I respectfully disagree; the ways in which Hum’s sound and perspective have shifted depend on that timeframe. The songs are longer, with stretches of meditative repetition drawn from stoner/doom metal. Matt Talbott’s lyrics largely trade the brightness of Downward highlights like “Dreamboat” for a lived poetic perspective on his fleeting place within nature, within humanity, within the galaxy, like Mount Eerie’s Phil Elverum writing bittersweet sci-fi memoirs. Inlet isn’t disconnected or displaced from the continuity of Electra 2000, You’d Prefer an Astronaut, and Downward Is Heavenward—there are riff-churning, melodically buoyant tracks here, don’t worry—but like Polvo’s return albums In Prism and Siberia, Inlet exhibits a band that did not stop evolving, even if the signposts of studio recordings did not appear to document that journey.

The eight tracks on Inlet sift into three different modes: mid-tempo melodic rockers, ultra-heavy evocations of stoner metal, and ponderous, introspective odes. The first category is the most populous, offering “Waves,” “In the Den,” “Step into You,” and “Cloud City.” (“Inklings” is curiously absent from Inlet, perhaps viewed as remnant of Downward instead of a step forward.) As much as I’ll argue that Inlet doesn’t exclusively traffic in the nostalgic thrall of a classic sound captured in amber, there’s no denying the dopamine rush of that guitar sound when the post-Loveless arcs of “Waves” hit. Those layers of immaculately crafted guitars offer an immediate, resuscitative balm, continuing to reveal new overdubs on the tenth, fifteenth, twentieth spin. “Waves” looks back upon past, unspoken struggles (“They don’t know of my solitary days”) as Talbott gazes off into an uncertain future, but there’s a comforting serenity to this distanced perspective as the song churns and crests, closing with “To see beyond the boiling sun / To the other side / And the wonders didn’t end.” The lack of an emphatic, hooky chorus in “Waves” (an element Hum deprioritizes for much of Inlet) is quickly rectified by “In the Den,” which offers the album’s most catchiest refrain. It’s hard not to appreciate “I am still alive and what's coming true / Is the signal to my return, oh! / Find me here on the ground and in need of you” as a meta-level statement on Hum’s reappearance, and the liveliness of that “Oh!” cannot be understated. If Inlet came out on a major label, there would assuredly be a single edit for “In the Den,” which rides its soaring riff almost seven minutes before fading out, but Hum’s propensity for savoring its work doesn't tip against the listener’s favor. “Step into You” is Inlet’s shortest song at just over four minutes and its most conventionally structured, switching between a satisfyingly chunky verse riff, a slowed-down chorus progression, and a silvery guitar solo. In contrast, “Cloud City” lets its sci-fi tinged verses (“Crowds would gather on the traces of the outer rings”) give way to the tremendous gravitational pull of the guitar workout black-hole where a chorus might have once lived, fueled by Bryan St. Pere’s best, most pummeling work on Inlet.

While those four songs offer a comfort-food buffet for starving Hum fans, “Desert Rambler” and “The Summoning” expand the menu’s offerings. The stylistic stamp of stoner/doom metal on Inlet is not without precedence: Matt Talbott’s bar Loose Cobra in Tolono, IL, has hosted Oktstoner Festival, and it’s a natural progression from the skeletal riff-and-repeat approach of Centaur’s songs. I recall being at Parasol after Centaur had played a show in Chicago with Pelican (having just released their untitled debut EP) and drummer Jim Kelly sang the band’s praises. It wasn’t a one-way relationship—the leads of the title track to City of Echoes demonstrate how much Pelican drew from Hum—and it’s on these songs that Hum reflects back upon some of the bands they influenced and remain within their orbit, whether that’s the continent-shifting churn of early Pelican, the metal-tinged instrumental rock of Ring, Cicada offshoot Dibiase (who’ve released an EP and an LP on Talbott’s Earth Analog Records), or the heavy slow-core group Cloakroom (who chose Talbott to produce their 2015 LP Further Out and got him to sing lead vocals for their b-side “Dream Warden”). “Desert Rambler” spans nine minutes, alternating between a mammoth verse riff that Talbott nearly has to bellow over and dreamy, barren bridges and choruses. Even before chiming notes swoop over the top of the machinery, there’s a impressive build-up of undercurrent textures (to the mystifying chagrin of the otherwise satiated Stephen Malkmus, a comment which at last connected my high-school fondness of both Hum and Pavement). “The Summoning” is somehow heavier and slower (who do they think they are, Pinebender?), but even with the foreboding crush of its main riff and the serrated edge of the harmonic accents, Talbott’s sheepish nature (“Let this be the last assumption that you were never wrong / I am ever wrong”) and detached perspective (“Just a twist and I'm gone / Through the ether and on to home”) offer a variation on the juxtaposition between form and content that initially drew me to Hum’s music. Given how Hum’s aesthetic leap on Electra 2000 was driven by predecessors and peers, adding the influence of their protégés on “Desert Rambler” and “The Summoning” while still scanning as Hum songs feels fitting.

Inlet’s final two songs are my clear favorites on the record, applying the analgesic guitar tones of the up-tempo tracks to the sprawling terrain of the Mesozoic stompers, and uncovering new lyrical depth in the process. “Folding” and “Shapeshifter” each stretch to eight minutes, hinging upon a very relatable combination of overwhelmed by what might come next and comforted by the lasting resonance of his loving relationship. “Folding” weaves a melodic lead around Talbott’s ponderous verses—“Do you feel tremors here? / Do you feel the same like you used to?”—then lets Jeff Dimpsey’s undulating bass line take hold before asserting “I could never be two / I’ve got it in for you” in the shimmering coda. The last two minutes of “Folding” quietly pulse as delay-drenched scrapes curl overhead, a ruminative enclave before Inlet’s closing track. “Shapeshifter” allows its evocative guitar line to play out in full before Talbott’s vocals come in, and there’s no better encapsulation of his lyrical appeal than its opening verse:

I remember the skies and the sand

I remember your face and your lovely hand

Words poured out on a dusty land

And gravity comes to us all

I feel the engines stall

Feel us start to fall

The chorus of “Shapeshifter” elongates its syllables into an immersive wash, floating over a slow-moving sunset. The bittersweet bridge—“While you let the water in / I dreamt again that I couldn’t swim”—builds into a C-Clamp-esque plateau of sustained guitar, and then switches to the cleaner chords of the song’s back half. The titular shapeshifting occurs as Talbott envisions himself as a butterfly, a fawn, and a bird, a fanciful sequence motivated by “Finding myself past the half-life of me” and pondering other forms of existence. This passage ties together the recurring themes of Inlet, and the record ends with the warmth of “Suddenly me just here back on the land / Reaching for you and finding your hand.” These two songs are part of a lineage with “Suicide Machine” and “Ms. Lazarus,” but the imagery has been refined, the emphasis on mortality no longer feels hypothetical, and there’s no drama within the relationship, only calming reassurance.

Listening to Inlet enacts a strange push-and-pull of going back and moving forward. I’m transported back to my high school days, to when my fondness for this band was at its most consuming, but I’m not trapped back in 1997, just recalling the past as the past. My enjoyment of Inlet isn’t dependent upon that timeframe: the album doesn’t resonate with me now solely because it would have resonated with me then. It resonates with me more now than it would have in high school. That’s a rare achievement for reunited bands (joining successes like Polvo and Slowdive), which involves passing up the easy move of wearing their glory days like an old t-shirt, regardless of whether it still fits. Sometimes that shirt does still fit, giving fans a swell of nostalgia for a rose-colored era and the band a rush of renewed adulation, but those swells and rushes subside as the present regains its focus. Inlet’s lyrics never inhabit the past. They look back, sure—the chorus of “Step into You” begins “Remember how / Your voice was an echo to me”—but Matt Talbott doesn’t write like he’s returned to his twenties or thirties. The same song rejects the temptation of writing from the past, closing its first two memory-chasing verses with “And everything here isn’t true” and signing off with “I am over it / I’m a dried-up, wind-blown cocoon.” Talbott is at peace with where he is now, and that’s where Inlet’s songs reside.

I’ll never experience Inlet with the same singular focus as I did You’d Prefer an Astronaut with the dubbed cassette and the daily bus rides and the feeling of entering an unfamiliar-yet-familiar world and staying there, but Inlet offers a different path to residing within the album on its own terms. While Hum’s fan base cheerfully revisits the past to help process Inlet (ahem), the band declines that journey. They delivered the album and backed off. There’s been a notable absence of promotional interviews for Inlet, with Bryan St. Pere’s pleasant, if not especially revelatory 2018 appearance on Joe Wong’s The Trap Set podcast remaining the most helpful link I can pass along. (Fingers crossed for a Matt Talbott appearance on Allen Epley’s Third Gear Scratch podcast, comparing notes over how Hum approached Inlet and Shiner approached their own reunion record, Schadenfreude.) There are no lyrics included with Inlet and only the barest credits on the album’s gatefold sleeve, let alone explanatory liner notes. No song-by-song walkthroughs exist to provide insight, no Reddit AMA to answer fan questions. No promotional videos. No livestreamed performances. No advance singles with exclusive debuts. Given how uncomfortable the members of Hum appeared with the machinations of major-label life—that awkward interview with noted fan Howard Stern, Matt Talbott and Tim Lash’s inexplicable chicken and bunny suits on 120 Minutes, their clear disinterest in fashionable turns like the Smashing Pumpkins’ goth-glam makeover for Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness—and how their only priorities seemed to be recording (and possibly re-recording) albums and crushing audiences with massive volume levels, it’s not a surprise that the band abandoned the promotional circus. Inlet is entirely on Hum’s terms: recorded at Talbott’s studio by Talbott, Lash, and Earth Analog house engineer James Treichler, mixed by Lash, released on Talbott’s label. No guest musicians, no outside producer. What’s absent is significant. It’s a bold gambit, dependent upon the size and voracity of the band’s audience. They delivered the album, this album. That’s enough.

I won’t provide a final verdict on Inlet or a qualitative ranking of Hum’s albums; I spent over twenty years with You’d Prefer an Astronaut and Downward Is Heavenward, so calling Inlet after five months seems cruelly premature. It’s an ongoing process, one that will continue after tour dates safely reappear and my eardrums have been bludgeoned by full-volume renditions of these still-new songs. I am, however, willing to declare my lingering astonishment over Inlet. I should not have been this surprised—there were good reasons why they held the title of my favorite band for a long time—and yet Hum was not content to merely remind me of those reasons. Much of their critical legacy is bound to a specific guitar sound, one that could be distilled, purified, and injected into a Deftones album, and Inlet both demonstrates how breathtaking the genuine article of that guitar sound can still be and reinforces the singularity of their songwriting, which continued to evolve in absentia. No matter how many bands have emulated Hum, only one band can write songs like “Folding” or “Shapeshifter.”

|

Three years between albums is not an eternity, but I was beginning to wonder if Ventura would deliver a follow-up to their mammoth 2010 LP We Recruit. Being an ocean away from the Swiss trio’s tour dates, I was left to dwell on their last proper release, a heartily recommended seven-inch released later in 2010 with David Yow on The Jesus Lizard on vocals. When a considerable part of your aesthetic is founded upon ’90s Touch and Go guitar rock (i.e., aggressive, tight, and bullshit-free), teaming with Yow is a potentially dangerous form of wish-fulfillment. I was ignoring the flipside of that coin: Yow was equally fortunate in the team-up, jumping from the Jesus Lizard’s reunion tour into a European vacation with a younger group with something left to prove. The lingering question remained, however: did they already prove it through this dalliance with a noise rock hall of famer?

Apparently not. Ultima Necat is not the product of a band resting on its laurels—it’s a significant step forward from the already impressive We Recruit. Few bands achieve the tonal consistency displayed here: its gravitational pull locks you into a seriously heavy and downright serious forty-two minutes. In true Touch and Go spirit, nothing gets in the way of the songwriting. The production is bruising but clean, delivering its monstrous heft without collapsing underneath it.

Extend that ethic to the lyrical approach, too. We Recruit had moments of gallows humor, but Ultima Necat never cheats its focus. Case in point: I initially anticipated that the album’s epic centerpiece, the nearly twelve-minute “Amputee,” would undercut its wailing refrain “I feel like an amputee / I want my legs back” with a smirk like We Recruit’s “Twenty-Four Thousand People” did, but Phillipe Henchoz instead goes deeper, repeating “I’d like to dance again” and “If that dance could be with you,” his voice breaking down as the riffs lock in. There’s a fearless honesty to it, like Brian McMahan’s wounded vocals on Spiderland: if someone laughs at the vulnerability displayed, they’re the idiot (who will get caught in the crossfire of the seven minutes of escalating riff warfare that follows).

Ultima Necat draws from other pairings of heaviness and vulnerability. The chord progressions of “Little Wolf” echo Hum’s Electra 2000, but its outro dives down to Mastodon’s hull-crushing depths. Henchoz revisits Come’s chord battles with the twangs of “Body Language.” “Intruder” starts out like a malicious version of Codeine, but abandons John Engle’s starker arrangements in favor of layers of back-masked guitars. “Very Elephant Man” head-fakes at the math-rock of Don Caballero’s For Respect before ascending into the territory of Sunny Day Real Estate’s LP2 (h/t Shallow Rewards). Closer “Exquisite and Subtle” floats Herchoz’s vocals and blurred, shoegaze-inflected guitar far above the rhythm section. It’s heavy, yes, but the tractor beam of the preceding eight tracks has been lifted, letting you drift out of orbit.

Even with near-twelve minutes consumed by “Amputee,” Ultima Necat still clocks with a perfect forty-two-minute runtime. Such economy proves essential; the album’s unblinking focus could have turned suffocating with the addition of a few more songs. Instead, I ride out the muscular plateau of “Exquisite and Subtle” and gladly start back at the top with the aptly titled “About to Despair.” Consider Ultima Necat written in pen in the upper echelons of my 2013 year-end list.

Ultima Necat is available digitally though Bandcamp, Amazon, and iTunes. However, it’s well worth importing a physical copy of the vinyl from Africantape or an American distributor for the gatefold sleeve alone.

|

I half-joked on Twitter last weekend that there should be a 22-year moratorium before writing about My Bloody Valentine’s M B V, exaggerating the vast difference between the wait to receive and the wait to critique. Naturally, it didn’t take long for the major outlets to disregard my edict. Some reviews rolled in Sunday morning—“I’ve listened to it three times and I was super high the first two but here goes”—before I even got a chance to hear the album. (Moral: Always bring your laptop on trips in case My Bloody Valentine follows through on their long-standing threat to finally release a new record.) Most took three or four days, like Pitchfork’s 9.1 Best New Music tag. Anything longer than that felt remarkably patient, like Chris Ott’s piece in Maura Magazine (subscription for iPhone/iPad only). By Friday, I was willing to break the edict myself for one simple reason: I wanted to write about M B V, even if finality of opinion is impossible now (or ever).

The central point that rang out to me, over and over, as I listened to M B V on repeat this week, was that it’s undeniably My Bloody Valentine. A significant percentage of my record collection owes intellectual royalties to Loveless—so many titles that extract a part of its appeal, cross-breed it with a newer movement, slavishly copy its technical approaches—but M B V reminded me more of what those bands lacked, not what they offered over this long-overdue return. That Kevin Shields’ guitar work can remain both inventive and familiar is a testament to the master, given how many others have explored his terrain. That Shields and Bilinda Butcher’s hushed vocal smears remain singularly intoxicating is an equal surprise, since that style was ripped off almost as often with far less notice. M B V initially stood out as a lazy title, but its shorthand is appropriate; at last, the other side of the “MBV meets” equation is empty.

Yet MBV needs to be (re)defined. Debbie Googe’s interview with Drowned in Sound can be read as liner notes for M B V, confirming that she didn’t play on the album, that the drums have been “added and then taken off at least once” (with Jimi Shields getting the first crack before Colm O’Ciosoig redid them), that Bilinda Butcher came in to do vocals but nothing else. All of these facts seem like eye-openers until I confirmed that virtually every one is a repeat of Loveless’s recording. Googe didn’t play on that record, Butcher didn’t play guitar on that record, O’Ciosoig’s drums were a mix of loops and live performance. (He did author the soundscape “Touched.”) Loveless took nineteen studios, whereas M B V took twenty-two years, but at their essence, they’re both Kevin Shields solo albums.

My main issues with M B V stem from this point—the drums are often seem like an afterthought, the bass is frequently challenging to locate. There’s a buried percussive pulse and a vague bass throb to the womb-like opener “She Found Now,” but if you finish hearing the song with anything other than the vocal coos or the careful swoops of the guitar in your memory banks, you must be Debbie Googe or Colm O’Ciosoig preparing for the next round of tour dates. The mid-tempo shuffle of “Only Tomorrow,” “Who Sees You,” and “If I Am” could pass for an under-rehearsed live band, but keyboard lullaby “Is This and Yes” only picks up a neighbor’s kick drum sound-check. “New You” is the sprightliest pop song on M B V and its up-front bass line is a major reason why. Much of the percussive attention on the album steers to the last three songs, which eschew the pretense of live drumming in favor of pounding (“In Another Way”) or swirling (“Wonder 2”) drum loops. This approach recalls Shields’ remix work in the late ’90s, which jumped on jungle and drum ‘n’ bass trends (see remixes of Mogwai’s “Mogwai Fear Satan” and Yo La Tengo’s “Autumn Sweater” for starters). The stuttering, headache-inducing “Nothing Is” marks the only point when one of Loveless’s descendents overshadows the legitimate follow-up for me; I’d rather hear the metallic repetition of Glifted’s Under and In (the side project of Hum guitarist Tim Lash).

It’s tempting to imagine M B V with a more prominent, more considered rhythmic foundation, but that impulse just redirects into the decades-old Loveless fan-fiction competition. If you want My Bloody Valentine with a sturdier, more forceful rhythm section, there are bands for that itch. If you want My Bloody Valentine with contemporary drum programming, there are bands for that itch. If you want My Bloody Valentine with no drums at all, there are bands for that itch. You can spend years—literally, I have spent years—tracking down those alternate permutations of MBV’s sound, and the most confounding aspect of M B V’s existence (reminder: a new My Bloody Valentine album actually exists) is reconciling decades of genetic experiments with the re-emergence of the real thing. Sometimes those experiments were successful, even to the point where other reviewers think My Bloody Valentine didn’t have to follow-up Loveless because the Lilys or Sugar or whoever else actually did.

I can understand if that roadblock cuts off some people from appreciating M B V, but repeating my central point, I’m overcome with relief that what I’m hearing is undeniably My Bloody Valentine. Even if “She Found Now” is a dream, it’s one I’ll feverishly try to document upon waking, but always fail to capture. “Who Sees You” lopes without urgency, but it’s to allow Shields’ woozy guitar lines proper room to sway. Yes, the lyrics of “If I Am” are nearly impossible to pinpoint, but that point doesn’t stop me from humming the vocal melody hours after hearing it. “In Another Way” may be propelled by a cyborg drummer, but its combination of aggressive riffs and floating melodies could outlast the throttling loops by hours without wearing thin. All of these moments reassert what My Bloody Valentine offers then and now, an inscrutable pairing of the vague and the specific, the tangible and the intangible.

Let me be perfectly clear, even if My Bloody Valentine themselves discourage the practice. M B V is neither Loveless’s equal nor superior. You don’t have to squint hard to see its flaws (and implying that they’re even present on Loveless can be seen as sacrilege). Unlike Loveless, it’s plausible that a few of My Bloody Valentine’s challengers surpassed M B V. But what they did not do was make M B V irrelevant or ineffectual. It still surprises, and not just through its mere existence. It still demands more listens from me, and not just because of its historical importance. It’s an album loaded with qualifying statements (“for a reunited band,” “for such a long layoff,” “for being from a different era”) that somehow sheds these statements. By the close of “Wonder 2,” I’ve stopped comparing M B V to my rolodex of descendants and focus only on the record at hand. That’s the achievement here, and it is by no means a minor one.

…

One final consideration: What if M B V opens the floodgates? Terrence Malick took twenty years to follow Days of Heaven with The Thin Red Line and has since been slowly accelerating his rate of output, with a shockingly large slate of projects on the horizon. That’s my desired result: Kevin Shields, ceaseless tinkerer, becomes Kevin Shields, creator of finished products. M B V’s existence in 2013 shocked me, but the release of two more My Bloody Valentine albums in the calendar year would not.

|

Champaign, Illinois’s Hum has reigned as one of my favorite bands for more than half my lifetime, but when I listen to their records, it’s easy to understand such devotion. Heavy but not plodding, spacey but always grounded, intelligent but still approachable, Hum’s trio of Electra 2000, You’d Prefer an Astronaut, and Downward Is Heavenward made the world of ’90s alternative rock a considerably more interesting place. While they’ve been essentially inactive since 1999, you can count on a reunion show every few years to satiate their legion of die-hard fans.

The only surprise about the release of Songs of Farewell and Departure: A Tribute to Hum is that it took this long to happen, given the number of Orange amplifiers the group helped sell. Pop Up Records issued The Nurse Who Loved Me: A Tribute to Failure back in 2008, and the cross-over in fan bases and influence is significant. Perhaps the lack of a big name like Paramore, who covered “Stuck on You” for the Failure tribute, delayed the release of its Hum-honoring counterpart, but Songs of Farewell and Departure did net a few groups (Junius, Constants, Actors & Actresses) that I’ve long suspected of pulling influence from Hum and a completely unexpected guest appearance from Jawbox / Burning Airlines frontman J. Robbins.

The big name that presumably escaped Pop Up’s grasp is the Deftones. Vocalist Chino Moreno has expressed his fondness for You’d Prefer an Astronaut and it’s easy to hear echoes of Hum’s heavy-yet-spacious guitar tones in countless Deftones songs. (I remember wondering if White Pony bonus track “The Boy’s Republic” was an overt nod to Hum b-side “Boy with Stick.”) The Deftones may be absent from Songs of Farewell and Departure, but their presence is still felt in the metallic approach taken by some of the groups. In a recent run-through of eighteen covers of the Smiths’ “Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want,” which included one from the Deftones, New Artillery collaborator/BFF Jon Mount said, “The Deftones are a litmus test for people who liked Hum for all of the wrong reasons.” While I disagreed with the sentiment to a certain extent, there’s a nugget of truth there. Hum’s endearingly nerdy tendencies—Matt Talbott’s scientifically inspired lyrics and thin singing voice (that cracked awkwardly throughout Electra 2000)—are not the source of their prevailing influence. Instead, those heavy-yet-spacious guitar tones are often picked up by groups already heavier and/or more aggressive than Hum in the first place, like the Deftones.

To help me sift through the sixteen covers on Songs of Farewell and Departure, I’ve recruited a peer from the Hum Mailing List days, Dusty Altena, who you may know from his blog, Tumblr, or Twitter.

SS: How many of these bands had you heard prior to this compilation?

DA: The only band I’ve heard of is Junius and J. Robbins (full disclosure: I am apparently not familiar enough with Jawbox to know Robbins by name). I love Failure too, but I had no idea who Kellii Scott was [the drummer on Fantastic Planet]. Sorry Kellii!

Is there a band you wish had made an appearance?

SS: It honestly would have been nice to hear the Deftones take on one of these songs. I suspect that Jesu's Justin Broadrick doesn't pull much influence from Hum records, but the thought of hearing a slow-motion rendition of "Isle of the Cheetah" from him is exciting. In a general sense, I wouldn't have minded hearing a post-rock band like Caspian take on one of these songs. The Life and Times could have done a good version of a song as well—they’d appeared on the Jawbox tribute record, so they’re a reasonable possibility. Bob Nanna of Braid / Hey Mercedes did a string of covers for his blog, so unless he hates Hum, I’m betting you could convince him to essay “Dreamboat.”

DA: I am an unapologetic Deftones fan, so I love your Deftones suggestion. I’d also love to hear some contemporaries like Jeremy Enigk, or maybe even Man…or Astroman. A Jesu post-rock cover is a great idea as well. I can’t think of any folk or semi-folk singers who’ve professed a fondness for Hum, but can you imagine a Jose Gonzalez-like cover? I would love to hear that.

SS: Let's get down to the bands that did appear on Songs of Farewell and Departure.

1. Arctic Sleep's “The Scientists”

SS: This is an entirely competent, if not hugely inspired beginning to the compilation. It's a very, very faithful take on the original, barring a few minor embellishments: heavier bridge, bigger drum sound, acoustic outro. It would have been great if they did something different with the song, though.

DA: I think competent is a perfect description for this track, ‘The Scientists’ is my favorite song on Downward Is Heavenward; but do I really want to listen to that same song with slightly different vocals? Not really. I’ll give you competent, maybe even good; but not inspired. I will admit that I dug the heavy drums and even the acoustic outro. But I was hoping for a much more original take.

2. (Damn) This Desert Air's "The Pod"

DA: I was really into the beginning of this one; it reminded me of Short Bus-era Filter. But by the time the chorus starts, it’s back to the same trap that most tribute albums fall into: faithful, faithful covers. At this point I just want to listen to the original, because it’s the same, and also better. The outro brings back that Short Bus palm-muting, and I have to admit I would love to hear the whole song reimagined on those terms.

SS: This one reminded me of a Failure / Quicksand hybrid. There’s potential here for a much more aggressive and ominous rendition if they’d ran with that palm-muting, but it follows the plot too closely.

3. Solar Powered Sun Destroyer's "Stars"

SS: If you had told me in 1997 that I'd one day hear J. Robbins sing on a cover version of "Stars," my head would have exploded. It's not that Jawbox and Hum were mutually exclusive elements in my record collection—Shiner is the explicit midway point between the two groups—but it's not a crossover I ever expected. Beyond Robbins' vocal take (which I like), Solar Powered Sun Destroyer's version adds depth but no major wrinkles.

DA: This is obviously intended to be the highlight of the album for most listeners. “Stars” remains that one Hum song that everyone remembers (even Beavis & Butthead). I still remember the night I was laying in bed and first heard this on the radio. It honestly changed music for me. I really like the post-rock intro on this version, but I don’t love the sharp enunciation, and I am not sure how I feel about the reimagined harmonies (seriously, I can barely recognize J. Robbins). This version is pretty damn close to the original, but you can hardly blame them—this song is crazy fun to play.

4. Bearhead's "Ms. Lazarus"

DA: We finally get to the first radical departure from the original. “Ms. Lazarus” was never one of my favorite Hum songs, but it had its place. This, I don’t even know what this is. I applaud the effort to make it different, but I cannot stand this alternative emo bullshit—these are basically 2006 Panic! at the Disco vocals—and I don’t want them anywhere near my Hum memories.

SS: It took me a second to figure out which song they were covering. The vocals are a non-starter for me (especially the “Shines I only wish that it was mine!” emo-thusiasm), but there are a few good rearrangements of the original guitar parts.

5. Anakin's "I'd Like Your Hair Long"

SS: Here are the nerdy vocals! Between the band's name and the vocalist not sounding like a dude chugging Muscle Milk, Anakin is in my good graces. It's not a drastically different version, but slowing down the song's main riff and adding cooed background vocals in the chorus are good calls.

DA: I like the slowdown, but the Ben Gibbard vocals annoy me. The further I trudge through this tribute, the more I am realizing how perfect Matt Talbott was as Hum’s frontman. Still, despite the Gibbardish singing, this is one of the more listenable songs so far. I will agree with you that the background cooing was a nice touch.

DA: Since Junius is the only band featured on this tribute who I am really familiar with and "Firehead" is one of my all-time favorite Hum songs; I was more excited to hear this track than anything else on the album. It passes the originality litmus test (one of maybe four other songs on this record)…but is it actually good? I would argue yes. It sounds almost nothing like the original—Hum’s intense subtlety is harder to grab than you would think—but it captures enough of the original while adding just enough unfamiliarity to make it interesting. It is definitely my favorite on the album so far.

SS: Co-sign on the success of Junius’s version. The big guitar/synth sound on the bridges is vastly different from the tone of the original, but fits the material perfectly. Even the vocal delivery, something that bothered me on The Martyrdom of a Catastrophist, fits well.

7. Constants' "If You Are to Bloom"

SS: This is a largely predictable applicable of Constants' space-metal aesthetic to "If You Are to Bloom." I wish they'd done an extended jam on it or something.

DA: Way too faithful for me. Once again, I immediately want to open iTunes to listen to the original. This is the exact same song with slightly different (and worse) vocals—the very same reason I generally avoid outtakes and demos. I feel like this song adds nothing unless you are a die-hard Constants fan whose dying wish is to hear them play a Hum song. My only praise is that the production reminds me of Keith Cleversley (YPAA’s producer), and I always wanted to hear what Downward Is Heavenward would sound like if it was produced by him.

SS: Wasn’t there a rumored first take on Downward helmed by Cleversley? I remember hearing that rumor at some point.

DA: I don’t remember ever hearing that, but I wouldn’t be surprised. Hearing a Cleversley-produced take on Downward will always be one of my Cancer Wishes.

SS: Have you seen Cleversley's site? Apparently he gave up producing a few years ago to get into shamanism.

DA: Ha! I hadn’t heard that, but that is amazing. I guess there isn’t much less to prove after perfectly producing one of the greatest records ever.

8. City of Ships' "I Hate It Too"

DA: Another faithful cover. At this point I would kill to hear Cat Power’s take on one of these tracks. Is the problem that it’s impossible to get at the essence of Hum without sounding like…Hum? The vocals are good, and so are the guitars; but, this honestly just sounds like an unreleased demo. It’s one of the better tracks so far, but that’s just because it sounds the closest to the original. So, what’s the point?

SS: This is absolute par. How many bands do you think took Hum’s gear list as a starting point for their musical careers and saved up for Orange amps? Do you think sounding exactly like Hum on a tonal level is the end goal for these bands?

DA: Judging by all of the @replies I get whenever I mention I own both pressings of You’d Prefer An Astronaut on vinyl, I would imagine that number is huge—I can’t think of any other band that has such a ridiculous cult following. I certainly remember buying MXR Phasers and salivating over Orange amps back in the day. I think a big part of playing Hum songs is trying to get that heavy-as-hell space sound that the band perfected.

9. Actors & Actresses' "Aphids"

SS: I can't tell of Actors & Actresses' version of "Aphids" is that much better than the covers which preceded it, or if picking a song I haven't heard eight million times is an enormous help. It's an interesting instrumental mix with softly delivered vocals that amplify, rather than disregard, the original vocal melody. Worth going back to a few times.

DA: "Aphids" has always been one of my least favorite Hum songs, but oddly, this is one of my favorite covers on the album. It feels like Actors & Actresses are taking a Hum song and making it their own rather than the other way around, and I truly appreciate that. I feel like these guys have come the closest to reaching that thin (and coveted) coverer/coveree relationship thus far.

10. Digicide's "Comin' Home"

DA: And we’re back to pseudo-Hum songs. In fairness, I don’t know how you’d cover this song and maintain the Hum elements while making it your own; but come on—this is basically the exact same backing track with slightly different (more emo) vocals. I honestly think (nu-metal band) Dope could record a better cover of this song. 10 times out of 10 I would rather listen to the original than this.

SS: Pseudo-Hum is right. Aside from some double-kick drum and the nu-metal scream of “And we wouldn’t know!” it’s a too-faithful take on “Comin’ Home.” Yawn. Speaking of takes on “Comin’ Home,” do you remember the original live version that was floating around before Downward came out? I always thought the chorus was “I’ll treat you like a son,” which killed me, but the It's Gonna Be a Midget X-Mas version is “I’ll treat you like a sound,” which I also like.

DA: Yes! I loved that version of “Comin’ Home”, and I think I might even still have an .mp3 of it somewhere. I listened to it enough to be bummed when such a different version appeared on Downward. That original was so powerful! There was an early bootleg of “Dreamboat” that was just awesome, too. Speaking of misheard lyrics; I always thought the end of the chorus on “The Pod” was “Wait, wait on me, yeah”, but on [Damn] This Desert Air’s version, it’s “Way, way on the end” (and what sounds like “Way, way on the edge” the second time). That puts the mood of the song in a totally different context for me.

11. The Esoteric's "Iron Clad Lou"

SS: I knew this was coming. The monotone post-hardcore/nu-metal bellow points its finger right in my face. The rigid arrangement opens up a bit on the bridge with dueling solos, but it all sounds like an exercise. No, you do not win.

DA: I actually appreciated this one. I loved the attempt to make it their own. Do I think it worked? No. But I will take this a thousand times over the “Comin’ Homes” and “If You are to Blooms” on this tribute. I appreciate the effort. Maybe it would work better with a band like Glassjaw, or something else along those lines. The Esoterics have me interested in the possibilities, which is more than most of these covers.

SS: I like the idea of a Hum tribute band named The Comin’ Homes.

12. Tent's "Little Dipper"

DA: I don’t even know what to say about this one. "Little Dipper" is arguably my favorite Hum song ever, but is this even a cover? The only recognizable element is the lyrics (which are barely audible in the original). I give them props for the crazy originality, but I feel like this is more in the realm of appropriation than cover. It’s not awful musically, but I feel like it’s a fork in the road pointing to A) Hum or B) Clouddead. Not exactly a cohesive take one of Hum’s more transcendent songs. Even after more than one listen, the music has absolutely no similarity to the original for me. I love Failure, but I’m not giving Kellii Scott a pass on this one.

SS: It’s a cover of “Little Dipper,” a song that thrives on its waves of guitar riffs, done with no prominent guitar parts. Instead, they’re replaced by up-front drums, piano, strings, and spoken word vocals that turn the sci-fi romance of the original version into weird threats. There’s heavy breathing, for fuck’s sake. You’re right that there’s no similarity to the original on a musical level, but I’ve heard covers that take that route and still succeed (Joel R. L. Phelps & the Downer Trio’s “The Guns of Brixton” comes to mind). What bothers me most here is the abandonment of the original sentiment.

13. Stomacher's "Why I Like the Robins"

SS: If you'd told me that one of these covers would be undone by an irritating vocal affect, I would have presumed it was Junius, but Stomacher sabotages an otherwise acceptable version of "Why I Like the Robins" with its overly manicured delivery. Most of it is par for the course, but they add some nice guitar textures to the outro.

DA: I never loved this song in the first place (except the song title, which weirdly has always been one of my favorites), but once again I am annoyed by the proximity (close, but worse) to the original. I can’t say I am actually irritated by the vocal effects as much as you are, but this song is more boring than the original and adds nothing new, save for a nice effects-laden outro.

14. The Felix Culpa's "Puppets"

DA: “Puppets” is one of my favorite Hum songs, but mostly because it’s recorded with an excitement by the band that isn’t found on any other release (perhaps due to the members switching instruments on the recording). This cover basically takes all of that excitement away, which is unfortunate. It isn’t horrible to listen to, but I feel like it’s lost its essence.

SS: This was when my “I really just want to listen to the original version” impulse kicked in. It’s a faded carbon copy. “Puppets” is a great song, but I don’t know how much any group could have done with it. Once you lose the forward momentum of the original, it falls flat.

15. Funeral for a Friend's "Green to Me"

SS: These Welsh post-hardcore/emo guys try their damnedest to turn "Green to Me" into a power ballad, but pulling out the heavy guitars, adding IDM-for-beginners beats, and going super MOR on the vocals just makes the song boring, if not elevator-ready.

DA: The intro was nice for all of about 25 seconds. Once again, someone emphasizes just how bad Hum would suck without Matt Talbott as the frontman. Even Guns’N’Roses could have made a better power ballad out of this song. (Although I wouldn’t be surprised to hear this on next week’s episode of Teen Mom.) This is probably the worst song on the album, despite the band’s effort to make it original (which I am usually on board with). My god, I just want to turn it off.

16. Alpha Stasis's "Scraper"

DA: I always hated "Scraper" back in the day because it was so hardcore, but I have recently come to appreciate it a lot more. This song does an okay job of capturing that energy, but as with the rest of the album, it is too similar to the original. The Electra 2000 version is better, and it’s actually Hum, so what’s the point of listening to this? There is absolutely nothing new brought to the song. Isn’t this why you start a band in high school—to cover your favorite songs and get them to sound exactly the same? I feel like this would have been an amazing song for J. Robbins to appear on. Can you imagine Scraper sounding like "Savory"? We can wish.

SS: Now you’re making me imagine how great an Electra 2000 covers record fronted by Jawbox-era J. Robbins would be. Thanks a lot.

I’m tempted to just criticize the original, which is one of the weaker links on Electra 2000. Its two-chord trade-off plods, Talbott’s delivery is trying, and the lyrics are painfully confessional without the filter of some science-fiction narrative. The best part is the spoken word bridge: “Say hi to your folks / be nice to your lunchmeat,” etc. Aside from tossing out that bridge, Alpha Stasis mostly gives “Scraper” a modern production update, at least until the nu-metal “Yours make me cry!” scream. I got a laugh out of that one.

SS: Wrapping up, are there any songs you’d wished a band had tackled?

DA: I would have loved to hear the namesake of the album, “Songs of Farewell and Departure” (always one of my favorite Hum songs). “Winder” would have been great. I also would have loved to hear a new take on “Shovel.”

SS: “Songs of Farewell and Departure” would have been a good pick. I would have liked to hear versions of "Afternoon with the Axolotls," "Winder," and "Isle of the Cheetah." Those all seem like songs that could be taken in vastly different directions and still hold up. Do you think a band could have done something different with “Diffuse”? Would you want to hear an aggro rendition of “The Very Old Man”?

DA: That’s a good question. I originally put “Diffuse” in my list of songs I would have wished for, but I took it off when I realized it probably would have just ended up another pseudo-Hum song. I think it would have ended up being treated the same as “I Hate It Too” or “The Pod”. “The Very Old Man” would be awesome, though. It’s always been my absolute least favorite Hum song, but I would love to see what someone (think Chad VanGaalen) could do with it.

SS: The moral of Songs of Farewell and Departure (and the vast majority of tribute records, to be fair) is that more of the bands needed to try different things with the material and actually pull off the concepts, not just aim for and easily achieve pseudo-Hum status. The hypothetical covers we've come up with interest me a lot more than the majority of songs here, although Actors & Actresses, Junius, Solar Powered Sun Destroyer, and Anakin deserve credit for their contributions.

|

|

I have a love/hate relationship with mail order. I owe a key chunk of my music collection to shipments from Parasol Mail Order, Newbury Comics, and the now defunct CDNow and Music Boulevard, since they granted me access to independent rock staples that I couldn’t find at either the nearby Rhino Records or Circuit City / Media Play / other defunct big box stores in high school. Yet as I’ve grown accustomed to shopping at record stores, including Parasol in Champaign and Newbury Comics in Boston, I’ve had less reason to rely on mail order, and with the threat of Somerville mail thieves, I dread the potential of an unsuccessful delivery. Maybe once I have a house in the suburbs [editor’s note: i.e., now] it’ll be a less pressing concern and I’ll return to my mail-ordering ways, but I’d much rather go out to a store and press my luck with stock than place an order and press my luck with neighborhood kids. If you’re willing to steal a copy of Rachel’s Systems/Layers, I’d consider limited edition vinyl fair game as well.

I’d mentioned this particular limited edition vinyl before, but it’s worth mentioning the specifics again—three colored LPs in a triple gatefold sleeve with embossed artwork. Mylene Sheath deserves special praise for one-upping vinyl-oriented labels like Temporary Residence and Hydrahead. (Okay, the Eluvium box on TRL is impossible to one-up, but still.)

96. Constants – The Foundation The Machine The Ascension 3LP – Mylene Sheath, 2009 – $25

Constants’ aesthetic blueprint could’ve been drawn from various parts of my brain. Take the churning space rock of Hum and Failure, add in the weight of post-metal groups like Isis and Pelican, then pull in a secondary dose of instrumental post-rock for the drifting passages. “Passage,” an emotional, heavy, dynamic rocker from an exemplary split single with post-rockers Caspian, was the perfect advertisement for The Foundation The Machine The Ascension. It put my hopes for TFTMTA through the roof, so it’s not surprising that the album doesn’t quite hold up to its imagined heights.

Although the sonic template is compelling and many of the songs are excellent, The Foundation has two key problems: the vocals and the length. The gang vocal approach works in small doses, which is why I enjoyed them on “Passage,” but over the course of an hour-long record, they often sound muddy. Multi-tracked vocals work best when you can hear different intonations from the various takes—Cat Power is exceptional at this trick—but too often Constants’ vocals blur together, detracting from the emotional impact and making for too many similar-sounding choruses. A more-is-less issue also pops up occasionally for the layers of guitar and keyboards, which reminds me of how effective Isis is when elements bob and weave instead of pile on top of each other. Constants use this approach from time to time—the beginning of the extended outro in “Passage” is a great example—but I suspect changing from two guitarists to one during the writing and recording of this album took away from some of the counterpoint between guitar parts.

The Foundation’s epic vinyl package is certainly impressive, but it would’ve been a noticeably better album if it had been condensed to two LPs. It simply lacks the instrumental variation to support 12 songs and 59 minutes. Highlights like “Genetics Like Chess Pieces,” “Those Who Came Before Pt. 1,” “Ascension,” and “Passage” feel buried rather than highlighted. Cut out two or three songs (“Identify the Indiscernables” and “Eternal Reoccurance” are prime candidates), trim the run time down by ten or fifteen minutes, and it’s a profoundly different album.

I’m likely being too hard on Constants and The Foundation The Machine The Ascension, since it’s not that far off from being a top-ten album for the year, but that’s what happens when you release such a beast of a song as the pre-album single. If you’re into Caspian, Pelican, Isis, Hum, Failure, or The Life and Times, there’s certainly something here for you, but I suspect that Constants’ next album will be when those elements converge into a thoroughly impressive album.

|

Considering that the only bands I see nowadays—seemingly, at least—are groups that I loved in high school (Polvo, Shudder to Think) that have reformed out of some combination of nostalgia and profit, adding Hum to that list shouldn’t be a huge surprise. Hum’s been doing these semi-reunions every two to three years since they officially went on hiatus with a New Year’s Eve show 12/31/1999. They played Furnacefest in 2003 (with a warm-up show in Champaign) and Rockfest in Champaign in 2005, so the two shows at the Double Door were right on schedule. The surprise, however, is that I was scheduled to be in Chicago for these performances. I had assumed that Hum would only play shows when I was firmly planted in the east coast, whether visiting family or moving there for graduate school. I was initially afraid that I’d missed my opportunity by waffling on the $65 New Year’s Eve show until it had sold out, but the addition of more manageable New Year’s Day show for $20 made my prior hesitation easier. I was going to see Hum for the first time in almost eleven years.

The only other time I saw Hum was at Irving Plaza in New York City in February of 1998 as a seventeen-year-old junior in high school. As we drove to the Double Door, my wife asked me what I thought of that show and I laughed, because it’s impossible to look back at that show with any semblance of a critical mindset. Getting to see my favorite band at seventeen was all shock and awe. Heroic Doses and Swervedriver opened up for Hum and I remember absolutely nothing about their sets. What I remember is the push of the billowing mosh pit, the thrill of hearing those songs live, the ringing in my ears from not wearing earplugs, and seeing Bush’s Gavin Rossdale and No Doubt’s Gwen Stefani as we waited outside of the club to meet the band. Tim Lash’s guitar tone? Matt Talbott’s live vocals? Bryan St. Pere’s fills? Beats me.

While I still count them as one of my favorite groups, it’s been years since I’ve listened to Hum almost exclusively. I’ll save the details of my full-blown Hum obsession and its passing for a pending article on You’d Prefer an Astronaut, but the short version is that I still listen to their last three albums from time to time, but not on a daily basis like I did in high school. (Sorry Fillet Show.) As frustrated as I was with the eleven-year wait, it did help my recharge my potential enthusiasm and/or nostalgia for the concert.

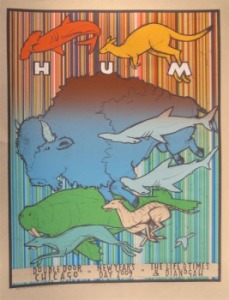

The openers for both shows were quite familiar for any Hum fan who kept track of their touring partners. Dianogah’s opening set displayed their progress since 1997’s As Seen From Above. Still channeling largely instrumental double-bass math-rock, Dianogah added some flair with female vocals on a few songs, accompanying guitar or keyboard on others, and a few aggressive songs that presumably were from their newest LP, the nigh-unpronounceable Qhnnnl. I’m tempted to pick that one up to bolster my copies of Battle Champions and the Team Dianogah 2 Swedish single, but I opted to pick up the Bird Machine posters for both evenings from poster guru and Dianogah bassist Jay Ryan.

As excited as I was for seeing Hum, I would have been just as psyched for a Shiner reunion (a group I saw eleven times in six cities, or, in other words, the anti-Hum), but catching Allen Epley’s The Life and Times again was a fine alternative. Their shoegaze-meets-math-rock aesthetic loses some detail in the live setting, but the songs from their forthcoming Tragic Boogie LP (coming out on Arena Rock Records in April) came across well. I missed hearing a few of my favorite songs from Suburban Hymns like “Mea Culpa,” “A Chorus of Crickets,” and “Muscle Cars” this time, but at least they played the excellent “The Sound of the Ground” from the Magician EP. Look for them on tour in the spring when their album comes out.

With a seemingly endless string of Rush songs between sets, I began to wonder if Hum was playing an elaborate joke on the audience. But once the smoke machine started up and the house lights dimmed down to a blue glow, Hum came out to enthusiastic applause and launched into “Isle of the Cheetah.” It didn’t take long for the first coordination hiccup to hit, but once the song’s intro passed and it hit overdrive, they were back on track. Tim Lash’s leads were spot-on in this song and throughout, and he even added some flourishes. Immediately I was struck by how metal the guitar tones sounded, especially Lash’s guitar, but that influence was always present during his tenure in the band. Everything else was as I remembered it: Talbott’s nerdy vocals bursting out with emotion on “The Pod,” Dimpsey’s solid bass lines, and Bryan St. Pere’s forceful drumming. I don’t remember Talbott being quite so funny at the Irving Plaza show, but the numerous Centaur shows I caught during college were as memorable for his stand-up bits as the actual songs.

The set represented their final three albums equally, with “Iron Clad Lou,” “Pewter,” “Shovel,” and “Winder” from Electra 2000, “The Pod,” “Stars,” “Suicide Machine,” “I’d Like Your Hair Long,” and “I Hate It Too” from YPAA, and “Isle of the Cheetah,” “Comin’ Home,” “Ms. Lazarus,” “Afternoon with the Axolotls,” and “Green to Me” from Downward Is Heavenward, plus the unreleased rocker “Inklings.” I was a bit surprised to hear the throat-scraping screams of “Pewter” and “Shovel” in concert, but the encore of “Winder” was an absolute thrill. I could gripe about “Little Dipper,” “Dreamboat,” “Pinch & Roll,” and “Diffuse” being absent from the set list, but the arc of the night worked well, with the main set ending with the extended outro jam on “I Hate It Too” (marred slightly by Bryan St. Pere losing his place for a few bars) and the encore ending with a rock-solid rendition of “I’d Like Your Hair Long.”

The best part of the evening was remembering just how great those songs are, whether it was the thunderous drum salvo that launches “Iron Clad Lou” into gear, the churning bass line of “Winder,” the guitar coloring for the mid-tempo “Suicide Machine,” the quiet intro of “I Hate It Too,” or the Cadillac-selling riff of “Stars.” Talbott’s lyrics are still wonderful, especially on the You’d Prefer an Astronaut, and it’s easy to overlook a few musical missteps along the way with that set list. Unlike some of the other reunited bands that I’ve seen, Hum never went away for long enough to forget the muscle memory of how to perform those songs or to lose the passion for playing them, so they’re essentially the same band put into cryogenic freezing.

It’s still somewhat astonishing that I finally made it to one of these shows. While I’d be thrilled if Hum released new music or at least recorded a studio version of “Inklings” and put it out as a single, the odds of either of those things happening are nil, so I’m glad that I could add something to my lingering super-fandom. I’ll just have to remember to be in Illinois in 2011.

|

|

Matt Talbott is apparently branching out from coaching high school football, since he's joined up with former Shiner members Paul Malinowski and Jason Gerkin (among others) for the next Open Hand record. He's featured on the untitled song at their MySpace page, which sounds like Downward Is Heavenward-era Hum with background vocals replacing some of the riffs. I have no idea if they're all part of the touring line-up or if this song is a one-off, but it bodes well.

Former Doris Henson/Proudentall frontman Matt Dunehoo is now in the NYC band Baby Teardrops. I skimmed a few of the songs, which didn't grab me as much as the highlights of Doris Henson's final record, Give Me All Your Money, but I'll keep an eye out for any official releases.

Bradley's Almanac has talked about Wye Oak on several occasions, so I checked out their Merge debut If Children. Perhaps it's the male/female duo that tipped me, but the record reminds me of a more rustic version of Folksongs in the Afterlife, whose Put Danger Back into Your Life is one of the most underrated records of the decade. Wye Oak has a similar appreciation for varying tempo and approach, although there are no bossa nova joints on If Children. They're playing Great Scott in Allston on May 2nd, but that is the week of too many damn shows, so I may not make it.

The Narrator has posted a song called "So the End" on their MySpace page, which surprisingly enough is about their impending demise. Like their R.E.M. cover posted at Stereogum, "So the End" furthers the folky resonance that popped up on All That to the Wall. The gang chorus of "I can't live on this witch's salary" sure bums me out. I'm still hoping to make it down to NYC for their final show.

Jon (of Stepleader/Juno documentary fame) has plugged singer/songwriter David Karsten Daniels a few times, so I finally got the hint and checked out his 2007 release Sharp Teeth and the new Fear of Flying, which comes out on April 29th on Fat Cat. I haven't fully digested either record, but "In My Child Mind You Were a Lion" from Fear of Flying is a clear highlight, displaying Daniels' expressive voice over a skeletal acoustic arrangement before ending on a wiry electric squall. Plus he can grow a pretty sweet beard, which is a pre-requisite for joining the indie folk movement. Sadly, I have proven time and again incapable of growing a burly beard, so freak-folk stardom does not await me.

|

|