First things first—go see my top twenty-five albums for 2011 here, then come back and comment on this post to tell me how wrong I am about my choices.

Now that the essential business is out of the way, allow me to go broad. I have a love/hate relationship with year-end lists. I love reading them. I love making them. I love debating them. But I hate the increasingly impossible logistics involved in them. I hate that I’m expected to have figured out my list by December 10th. I hate floundering when I see a trusted source recommend an album I haven’t yet heard on December 15th. I hate knowing that I didn’t spend enough time with an album everyone else loves. I hate the fact that so much stock is put into a sampling (top 25) of a sampling (top 30 or 40 candidates) of a sampling (all of the albums I heard this year) of an ocean (all of the albums released this year). I hate skirting the issue between “best,” “favorite,” “top,” and whatever other markers of greatness are used. But I love making my yearly list too much to stop.

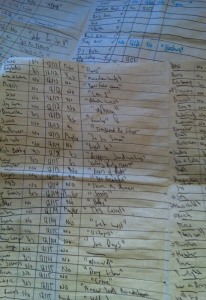

This year I approached it differently. Instead of taking stock of my favorites on December 1st and creating my list, I took stock of as much as I possibly could. Virtually every 2011 release I had in iTunes. (This choice excluded a huge chunk of material I'm simply too lazy to port into iTunes.) Notable or intriguing albums that appeared on other year-end lists. During December I listened to 150 albums from start to finish, proving that there’s no obsessive-compulsive task I won’t stupidly tackle. True to form, I mostly listened to these albums in alphabetical order. I made ridiculous charts, shown above, to track which records I listened to when, whether they were candidates for the final list, and my favorite track. All normal stuff.

I have done insane, ridiculous projects before, but this one might take the cake. Considering that I barely did any listening during a four-day vacation early in the month, I plowed through an average of six albums a day. Whatever I was doing—driving, working, washing dishes, reading, wrapping presents, painting—had an arbitrary soundtrack. (The strangest pairing? Painting the nursery to Tyler, the Creator’s Goblin.) I even found time to revisit favorite albums to let them sink in.

The biggest conclusion? It helped, adding three albums to my list, but it wasn’t enough. I could listen to another 100 worthy records and still have that sinking feeling of missing out on great music. I wasn’t dismayed by this conclusion, however, since it confirmed my suspicion that there’s no perfect list, even/especially my own. There are hundreds of excellent albums released every year and variables like taste, exposure, and audience dictate how various publications/writers sift those albums into their own lists. There’s plenty of cross-over between my list and Pitchfork’s, for example, but significant departures as well. If nothing else, I now feel capable of determining which albums would be appropriate for particular publications' lists. It's like I'm an actual music critic!

My initial intent was to write fifty-word blurbs for each of the 150 albums (I somehow completed 120+ of these), but midway into the project I realized that my comments on individual albums were less interesting than the connections between releases. I may complete/post those blurbs a few weeks from now, but the talking points below are of greater importance. I’ve also included a supplemental list of honorable mentions. After all, there’s no use in listening to 150 albums in a month if it doesn’t produce heaps of self-indulgent writing!

Catching Up Is Hard to Do

There’s an unrecognizable moment when the arrival of old favorite’s newest release switches from “I’ll listen to this album immediately and half-heartedly enjoy it” to “I’ll download this album and never put it on.” My iTunes is littered with previously unplayed records from past notables—Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, Centro-matic, Glossary, Twilight Singers, etc.; releases that fans of those artists recommended wholeheartedly, recommendations I then ignored. When I finally heard these albums, I had three divergent responses. In the case of Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, I recognized that Wolfroy Goes to Town was very good at what it does—stripped-down folk—but my appetite for that style went away years ago and has not returned. In the case of Twilight Singers, I struggled to ascertain why Greg Dulli’s songs no longer appeal to me. Ten years ago I couldn’t have imagined that a new Dulli album would fester on my hard drive for months. Is Dynamite Steps the latest in a string of fandom-testing releases (Amber Headlights, She Loves Me, Powder Burns, The Gutter Twins), has the appeal of Dulli's sex-driven noir worn off, or have I changed more than Dulli has? Perhaps that’s the problem. I'll be a father next year and the thought of bringing my future daughter into a world with Greg Dulli in it gives me the creeps. Finally, in the case of Centro-matic (and to a lesser extent Glossary), I slipped back into my old fondness with ease. A superlative rock song like “All the Takers” certainly helps matters.

I’ve thought about this issue plenty before now, but there’s an obvious reason why I haven’t written about it: I don’t write about albums that I haven’t listened to. I’ve been tempted to make an entry into The Ten for favorite artists/bands who’ve inexplicably fallen off my radar—Do Make Say Think after You, You’re a History in Rust and Dirty Three after She Has No Strings Apollo to name a few—because it gets at the heart of the “Is it you or is it me?” It’s much easier when a band drops precipitously in quality (I’m looking at you, Minus the Bear), but much harder when there’s nothing obviously bad about their new output. Perhaps at some point, you've just had enough.

Subjectivity/Objectivity and Best New Music Achievements

The biggest thing I struggle with when listening to and writing about music is my preference for the subjective over the objective. There’s a sense of relief when a great album appears that I can relate to—hello, Wye Oak’s Civilian—but I’ll be the first to admit that records that don’t apply to my social situation or even strive against relatability often fall outside of my listening pile. Hearing music on a purely objective level isn’t impossible for me, but it’s not something I often choose to do.

No time better than the present to change that habit, since this undertaking required heavy doses of objective listening. The subjective listener in me would quickly changed records when something like Das Racist’s Relax came on, but if I’m going to listen, I might as well make the best out of it. This tact mandates an objective approach: can I understand why this record garnered critical acclaim, even if it doesn’t suite my tastes?

For the most part, the answer was yes. I can understand how Girls’ Father, Son, Holy Ghost’s referential streak mines decades of pop music (although the tired boogie-rock riff of “Die” nearly gave me an aneurysm). I can see how PJ Harvey’s Let England Shake is an important album for that nation in this era, even if it feels like assigned reading to me. I get how Cut Hands’ Afro Noise I reconstitutes African rhythms as percussive noise treatments without sounding like an imperialist incursion. (If the whole album sounded like superior versions of Brian Eno’s ’80s records, e.g., “Rain Washes Over Chaff,” it would have made my list.) I can see how Destroyer’s Kaputt thoroughly modernizes late-period Roxy Music and saxophone-heavy yacht-rock, even if I view the latter point as a war crime.

Here’s one notable exception: I enjoy past M83 releases, but Hurry Up We’re Dreaming confirms my suspicions that they’d be better as a singles band. Citing Smashing Pumpkins’ Mellon Collie & the Infinite Sadness as a dominant touchstone but not correcting its hubristic indulgence is a huge misstep. The issue here is that Hurry Up needs to be heard subjectively, since Anthony Gonzalez’s fixation on youth kills even an objective view of his own influences. I suspect that sixteen-year-old girls aren’t complaining about excessive filler.

If Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming mandates a particular subjectivity, does the inverse exist? Is it fruitless to even try to hear some albums subjectively? Do certain albums require objectivity? It’s hard to apply that designation across the board, but on a personal level, I’ve started calling albums that only appeal to me on an objective level “achievements.” Ironically, I came up with this idea while listening to St. Vincent’s Strange Mercy, an album that initially appealed to me because of Annie Clark’s bonkers guitar tones, not her role-playing-centric songwriting. There’s still the icy chill of art-rock to Strange Mercy, but “Surgeon” and “Year of the Tiger” prompted me to keep with St. Vincent and now I’d exclude it from the backhanded compliment of “achievement.”

Token Selections

Pitchfork’s recent dismantling of Childish Gambino’s & started with a hilariously accurate line: “If you buy only one hip-hop album this year, I'm guessing it'll be Camp.” (The review may have been directed at Community super-fan Todd VanDerWerff of the AV Club.) It’s not applicable to me in the specific case of Donald Glover’s attempts to mimic Kanye West—which I nevertheless suffered through as part of the 150—but it does touch upon the general sense of tokenism I feel when only one hip-hop album, Kendrick Lamar’s Section.80, makes my list.

Listening to 2011 releases en masse made me appreciate such variety, however selective it may seem. When I looked to add recommend titles to my list, many of them were hip-hop albums. Even I get exhausted of gauzy dream-pop, nu-gaze rituals, and dude-rock abrasions. (You got me—I never tire of dude-rock.) Most deviations from my standard sub-genres were appreciated, especially the joke-rap of The Lonely Island, even if I knew it had no shot at the actual list.

This thread ties into that overall sense of flustered inadequacy: you can only spend quality time with so many albums per year, which means some genres/artists/styles are ignored. There’s also a dog-chasing-its-tail element at work; since I listen to less hip-hop, I’m less comfortable writing about hip-hop, so I’m less likely to listen to it in order to write about it. (Exhale.)

There is a silver lining. Not only was I energized by listening to Kendrick Lamar, Shabazz Palaces, DJ Quik, and A$AP Rocky, meaning that I’ll likely spend more time with Passion of the Weiss’s highlighted titles in 2012, but there’s precedent of my shifting genre preferences. Back in 2005, my fondness for post-rock was apparent, but it hadn’t crossed over to ambient yet. Tim Hecker appeared in 2006. Stars of the Lid, Eluvium, and Nadja appeared in 2007. This year, five artists (Christina Vantzou, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Grouper, Tim Hecker, and list-topper Julianna Barwick) qualify as ambient. Tastes change; a “token inclusion” genre from 2006 now dominates my listening.

Wife-Core

When coming up with the master list of albums to hear, I made a few exceptions for albums already in iTunes—I’d previously reviewed …And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead and National Skyline’s latest releases and could safely bar them from consideration—but titles added for my wife weren’t given exemptions. There’s enough cross-over in our taste (Wye Oak, The Antlers, and Low would also make her hypothetical list) that I’m rarely forced to endure indie-folk water-torture. I also act as a filter for what she would enjoy—in the case of new spins, Ohbijou’s Metal Meets—so the surprises are few and far between.

Her favorite album of the year, Bon Iver’s Bon Iver, is hardly a surprise. It’s topped big year-end lists. It’s sold 300K+ copies. I saw a performance of “Calgary” (with Colin Stetson!) on The Colbert Report. But had I actually listened to it before? No. While I’m unlikely to join the Paste Magazine white-power movement on Bon Iver, I’ll admit that aside from the Richard Marxist “Beth/Rest,” it’s worthy of obsession… for those who practice yoga weekly. Which my wife does!

Three other wife-core notables proved more difficult spins. Fleet Foxes’ Helplessness Blues is a remarkable replication of the lush harmonies and thoughtful arrangements of ’60s and ’70s folk, but subjectively, it could not appeal to me less. Iron & Wine’s Kiss Each Other Clean is a further abandoning of Sam Beam’s old whisper-folk days, even catching the Great Saxophone Plague of 2011, but hearing him play ’70s funk-rock is not on my to-do list. Death Cab for Cutie’s Codes and Keys technically appealed to both of us, seeing as its twenty-something chick-rock was purportedly influenced by Brian Eno’s Another Green World, but it lacks the big hooks its core audience salivates over and the level of songwriting detail that appealed to me about their early work. The irony of these three albums came when I told my wife I wasn’t a big fan of them—turns out neither was she, having barely listened to any of them.

Stumbling Block

There’s a single characteristic that can prevent me from enjoying an otherwise commendable release: vocal style. I have a gag reflex to certain styles that I’ve worked hard to correct—I came around on Björk just in time for her string of concept-heavy, songwriting-light releases—but sometimes there’s not much I can do beyond writing a formal apology.

Dear Marissa Nadler, I know I would love your newest self-titled album if I could get past your vocal mannerisms. When you dial them down on “Baby I Will Leave You in the Morning,” I’m on board, but elsewhere I can only shrug at my own hurdles. Someday I’ll get over it, I swear!

Dear Adam Granduciel of The War on Drugs, I am terribly sorry that your penchant for Bob Dylan’s elongated enunciation, e.g., “leeeee-nan” for “leaning,” has prevented me from fully appreciating your band’s newest release, Slave Ambient. Between the Dylan-esque delivery and Tom Petty tempos, you’re inadvertently channeling the six songs my sister played over and over when she was in high school. Nice guitar work, though! P.S., please do not cover Warren Zevon’s “Werewolves of London.” It would kill me.

Dear Hayden Thorpe of Wild Beasts, a friend continues to plug Smother and I want nothing more than to agree with him on it, but your highfaluting delivery is denying that opportunity. That delivery’s appropriate for your Talk Talkian music, too, so I’ll admit to being in the wrong. Perhaps this situation was fated by your parents, who could have named you Ralph or Chuck.

Honorable Mentions

Astute readers will notice that I bumped my usual 20 selections up to 25 this year, but I could have easily gone higher. The following ten albums were the last cuts. I've included a favorite track from each, but spared you the wrath of more blurbs.

Battles’ Gloss Drop: “Africastle”

Brief Candles’ Fractured Days: “Small Streets”

DJ Quik’s The Book of David: “Killer Dope”

Dominik Eulberg’s Diorama: “Wenn Es Perlen Regnet”

Ford + Lopatin’s Channel Pressure: “Too Much Midi”

Iceage’s New Brigade: “White Rune”

Idaho’s You Were a Dick: “Flames”

Junius’s Reports from the Threshold of Death: “Transcend the Ghost”

Stephen Malkmus & the Jicks’ Mirror Traffic: “Stick Figures in Love”

A Winged Victory for the Sullen’s A Winged Victory for the Sullen: “A Symphonie Pathetique”

There you have it! I conquered 2011!

|