I first noticed that Continuum had chosen an author for a 33 1/3 book on a Wire album when I was checking out who else on Last.FM was obsessively listening to early Colin Newman solo records. Lo and behold, one of my fellow devotees had been slotted to write the book about Pink Flag. This moment occurred shortly after I’d narrowed down the records that I could conceivably write 33 1/3 books about—barring all of my preferred options that would never be accepted (Juno, Shiner, Hum, Castor, Jawbox, Silkworm, Shudder to Think)—to Wire and Slint albums, with the possible addition of Girls Against Boys’ Venus Luxure #1 Baby, so reading his announcement was bittersweet, just like it’ll be when someone is chosen to write about Spiderland.

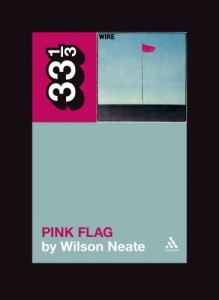

I can understand why Continuum chose Pink Flag, since it probably has the largest cross-over appeal of the three early Wire records, even though I would have opted for either the post-punk perfection of Chairs Missing or the unrelenting progress of 154. Whereas those two albums are firmly in the post-punk camp, Pink Flag occupies a liminal space between punk and post-punk, a concept that Wilson Neate investigates during the first half of the book. While no one explicitly stated this viewpoint in the book, I’m sure there are punk-rockers out there who love Pink Flag but have no time for either Chairs Missing or the willfully difficult 154. Those punk rockers and their post-punk peers will be well served by Neate’s book.

Neate’s Pink Flag is divided in two rough halves: the first five chapters are devoted to biographical, historical, and contextual coverage and the massive sixth chapter provides commentary on each song. Considering that Kevin Eden’s Everybody Loves a History speeds through much of this period in order to give equal space to the group’s post-Wire output and post-reformation material, Neate’s thorough exploration of Wire’s early years is quite welcome. Eden’s book glosses over George Gill’s tenure in the group, but Neate emphasizes how Gill’s clichéd rock ‘n’ roll approach gave the other four members something to model their minimalist approach against. The Clash provided a similar model, which led to some cold interactions between the groups. Wire? Cold? Never!

Doing the song-by-song approach works for some 33 1/3 books (Double Nickels on the Dime in particular) and it could have easily been the bulk of this book, given that Pink Flag has 21 tracks and the chapter spans 60 pages. Neate notes how several correspondents had difficulty extracting favorites from this string of songs, viewing it more as one complete document, which I can understand to some extent. Certain songs—“Reuters,” “Ex-Lion Tamer,” “Pink Flag,” “Mannequin,” “12XU”—stick out to me, but there’s a string of others, especially on side B, that flow together. Reading about them as separate songs shortly after I’d listened to the record was quite interesting, but I still had a hard time remembering a few of the songs’ melodies.

The post-script is relatively limited, jumping from just after Pink Flag to Elastica’s appropriation of “Three Girl Rhumba,” to that song’s use in a British H&M ad, and finally to Bruce Gilbert’s self-removal in 2004. It’s a transition focused on the financial side of the band, in which Colin Newman redid the writing credits for Pink Flag to give himself more royalties (he’d written the majority of the guitar parts, but Bruce Gilbert played most of them on the recording). Neate makes the point that the rock side won out over the art side, which is quite clear to anyone who’s read Object 47, Wire’s first post-Gilbert LP. Bits of Wire’s post-Pink Flag history are sprinkled throughout the book, but don’t expect any emphasis on “Outdoor Miner” or “The 15th.”

My biggest critiques are editorial in nature. At 150 pages, Pink Flag is on the long side of 33 1/3 books, surpassed in my stack by only the tomes on Bee Thousand and Exile on Main Street. The length would be fine if not for thematic repetition in the first half of the book, in which various points (Wire’s minimalism in particular) are reinforced several times over by multiple quotations. Graham Coxon provides an undue amount of these quotations, which baffles me in the presence of Albini, MacKaye, Prescott, Rollins, Watt, etc. Ultimately, Pink Flag the book would have benefitted from some of Pink Flag the album’s signature economy.

Despite these minor caveats, Neate does an excellent job bringing a Wire album to the 33 1/3 canon, finding a similar level of success to Bob Gendron’s Gentlemen. I doubt that most fans have tracked down Everybody Loves a History, but Pink Flag is a more succinct, more focused option for those who do not care to read about the genesis of The Ideal Copy. I’m holding out hope that Wire is granted one or two more entries in the 33 1/3 series, since Chairs Missing and 154 deserve equal treatment, but barring a major shift in Continuum’s approach, that’s not going to happen, so go pick up Pink Flag.

|