Is it possible to undersell Brian Eno? Between his involvement in the creation and/or production of a towering stack of classic albums and his semi-accurate statements that he invented ambient music, * his legacy speaks volumes for itself. But therein lies the most wonderful aspect of Brian Eno fandom: there’s always more to find. Between his rock-oriented solo albums, ambient albums, world music–informed albums, and a steady stream of collaborations of all three varieties, not to mention those essential producer credits, Eno’s relentless creativity provides seemingly unlimited avenues to explore, especially if you enjoy differentiating between minimal ambient landscapes.

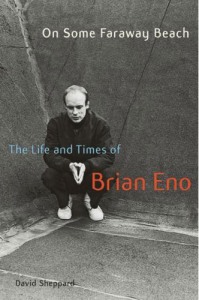

This broad swath of material is often bound together through the mythology of Eno, embodied by those Oblique Strategies cards he created in 1975 with Peter Schmidt. Yet sifting through the mythology (often self-created, since Eno’s a master of subtle self-promotion) to reveal the history is quite rewarding. I caught a glimpse of him at work in Hugo Wilcken’s excellent 33 1/3 volume on David Bowie’s Low, but that’s just one brief segment of Eno’s career. Fortunately David Sheppard’s well-researched On Some Faraway Beach fills in most conceivable gaps in this knowledge, documenting Eno’s upbringing, his aesthetic shaping in art school, his tenure in Roxy Music, his ventures into heavily collaborative solo recording, his high-profile production duties, and his more recent forays into visual art and political commentary. Have I mentioned the women? It documents them quite well.

Much like the Zane Grey biography I proofread for the University of Illinois Press (a remarkably entertaining read even if you care nothing about the pulp Western author), On Some Faraway Beach’s biggest revelation is its subject’s sexual appetites. I’d assumed that Bryan Ferry’s debonair profile received most of the female attention in Roxy Music, but Eno’s flamboyant style and more extroverted demeanor earned him the lion’s share of female attention. It even contributed to the strife between the two that eventually led to Eno leaving/being forced out of the group. The details of Eno’s lust—his supposed appearances in a few pornographic films prior to his musical fame, his vigor and stamina keeping his unfortunate tour roommate up all night, the Polaroid photos which catalogued his conquests, the autobiographical origins of “The Fat Lady of Limbourg”—can be difficult to reconcile with the calm beauty of Music for Airports, but it certainly makes sense with the more graphic allusions of his first two albums. Eno’s romantic life has some less sordid details as well, including writing the lovely “I’ll Come Running” for his then-girlfriend Ritva Saarikko (a Finnish photographer who took the cover portrait for Before and After Science) and the ongoing personal and professional success of marrying his manager, Anthea, in 1988. Perhaps the most revealing anecdote is a quick story about Eno’s flirtations with women on New York City streets in the late ’70s, approaching random strangers with semi-systematic approaches.

That idea of strategic chance dominates the discussion of Eno’s own music and production duties. Beginning as an avowed non-musician musician, Eno picked up second-hand tape recorders en masse to see how each one varied in sound. By the time he joined Roxy Music, he was quite adept at plumbing the depths of his synthesizer for new sounds, if still naïve of musical theory. Much of his solo work relies on three conditions: bringing in talented collaborators, challenging them to leave their usual approaches behind, and forcing himself to think on the spot. This emphasis on process resulted in both the pruned beauty of Another Green World and the elongated, frustrating genesis of Before and After Science; the improvisational collaboration with Robert Fripp on No Pussyfooting (which cost practically nothing to record and yet sold as astonishing 100,000 copies) and the detailed collages of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts with David Byrne; the ease of working with Daniel Lanois and brother Roger Eno on Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks and the contentious work with John Cale on Wrong Way Up. What On Some Faraway Beach stresses is the variety of these situations: sometimes Eno turns on a loop machine and records an ambient classic with infuriating ease, other times he tinkers endlessly on the final product.

Eno’s production career shares this range of process-dictated success, with the key variables being the artists’ willingness to experiment and the level of additional help Eno had in the studio. I was quite surprised to learn that Devo—having gallingly declared that their debut LP would be recorded by either Brian Eno or David Bowie (who’d agreed, only to back out due to scheduling conflicts)—were the most resistant to Eno’s oblique strategies, with Mark Mothersbaugh later regretting their know-it-all attitude. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Eno’s heavy involvement in Talking Heads’ Remain in Light might be the most artistically fruitful and hands-on record on his credit sheet, going so far as Eno’s request that the album be credited to “Talking Heads and Brian Eno” (after all, he wrote the vocal melody for the chorus of “Once in a Lifetime”!), but Tina Weymouth and Chris Frantz hardly shared David Byrne’s brotherhood with Eno. Weymouth even went as far as reinserting her deleted bass performances after Eno left the board. Eno’s involvement with Bowie’s Berlin Trilogy finds a healthy middle ground between these poles. With Tony Visconti helming the sessions for Low, “Heroes,” and Lodger, Eno was free to come in for a few days, challenge the status quo of the recording sessions, and leave once things had been adequately toppled. By Lodger this arrangement had lost some of its spontaneity, but Bowie lauded Eno’s involvement and eventually collaborated with him again on 1995’s Outside.

On Some Faraway Beach loses steam once it hits the mid-80s, specifically with the discussion of his involvement on U2’s albums. While those albums—particularly The Unforgettable Fire, The Joshua Tree, and Achtung Baby—provide enough interesting anecdotes (like Eno getting so sick of the endlessly fussed-over “Where the Streets Have No Name” that he nearly trashed the master tape or the fact that the infinite sustain guitar the Edge played on “With or Without You” was one of just three in the world) to keep me moving along, the depth of the treatment doesn’t match the earlier eras. Condensing the 20+ years from The Unforgettable Fire to the completion of the book in 2008 to a mere 70 pages results in too many projects getting tossed into veritable laundry lists. To wit: Eno’s involvement in Slowdive’s Souvlaki receives a mere half-sentence of discussion. Whether it or countless other projects from the ’90s and ’00s deserve equal attention to, say, Remain in Light is debatable (one I pick up in a review of Music for Films III), but it’s impossible not to feel the rush of wind when Sheppard puts the pedal to the floor.

Given Eno’s remarkably prolific nature, the lack of a discography appendix is disappointing, specifically because On Some Faraway Beach: The Life and Times of Brian Eno piqued my interest in so many of his albums—both familiar and unfamiliar. This discography provides a good start, but Sheppard’s informed opinions into these albums provide a wonderful road map, as long as you’re willing to do some serious flipping back and forth with the index and add a bunch of entries to your musical shopping list.

Don’t dawdle on these shortcomings. On Some Faraway Beach hits all the right big notes—it contextualizes Eno within the various phases of his career, it reveals the strategic choices behind some of his best work, it illuminates the corners of his very long, very storied career–and most importantly, it provides countless “Did you know?” anecdotes for your next Eno-themed dinner party. (The most curious fact? Both Brian Ferry and Elton John auditioned for King Crimson’s vacant vocalist slot in 1971.) Almost assuredly you have some form of an “in” for Eno’s catalog, and unless it’s one of his later albums or production jobs, On Some Faraway Beach is bound to increase your appreciation of it. Trust me—I spent a solid two weeks listening to Another Green World over and over again, marveling at one of my favorites with renewed interest.

* Here’s my take on whether Eno invented ambient music: No and yes. No, he was not the first or the only person to come up with the idea of passive listening. Erik Satie coined the term “furniture music,” contemporary composers like John Cage, La Monte Young, Steve Reich, and Terry Riley became practitioners of particular forms of it. But if we’re talking about the roots of modern ambient music—the minimal landscapes of Stars of the Lid, Labradford, Eluvium, etc.—or “chillout” electronic music, yes, Eno is the primary forefather of those movements (if by no means the sole influence). Coining the term “ambient music” certainly helps his case.

|