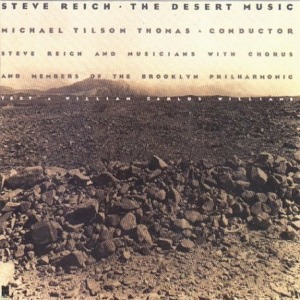

Steve Reich – The Desert Music LP – Elektra, 1985 – $6.50 (Mystery Train, 5/16

I find myself sticking with a few of Steve Reich’s pieces more than others, specifically Music for 18 Musicians, Octet / Music for a Large Ensemble / Violin Phase, and Six Marimbas, but it wasn’t until I picked up The Desert Music that I understood why. Those pieces were all composed in the 1970s and are formative explorations into minimalism. There isn’t a prevailing theme to Music for 18 Musicians, it simply goes. Those compositions set up the rules, the boundaries, and the elements for Reich’s later releases.

His major compositions in the 1980s—Tehillim, The Desert Music, and Different Trains specifically, for the simple reason that I own and have heard them—apply topical themes to these elemental templates. Tehillim evokes Reich’s Jewish heritage; The Desert Music follows William Carlos Williams’ poetry into the very idea of deserts; and Different Trains juxtaposes Reich’s frequent train trips in 1939–41 with those of European Jewish children headed off to Nazi death camps during the Holocaust. It’s heady, important stuff, especially Different Trains, and I commend Reich for taking this direction. He could have easily been content to explore the form’s more distant corners with different instrumentation (like Pat Metheny’s guitar performance of Electric Counterpoint that follows Different Trains on the LP) or plied his trade on film soundtracks, but bringing an emotional, personal, and historical resonance to his compositions is far more rewarding. More recently his 2006 release Daniel Variations focused on Daniel Pearl, the Jewish-American journalist beheaded by a Pakistani militant group in 2002.

The disconnect between Reich’s elemental 1970s compositions and his thematically charged 1980s compositions comes down to ease of listening. When I reviewed Octet / Music for a Large Ensemble / Violin Phase last year, I called it “remarkably flexible music,” noting how I frequently listened to it while working, driving, or reading, not just in active-listening scenarios. Whether Different Trains works in these passive contexts is up for debate, but it’s difficult to ignore the thematic arc of that release. The Kronos Quartet’s stuttering strings are just as disconcerting as the conversation snippets. Tehillim faces a different hurdle: I don’t share Reich’s Jewish upbringing. While that didn’t stop me from enjoying Mogwai’s “My Father My King,” I suspect that Tehillim is a far richer experience with the proper background.

On the surface, The Desert Music isn’t much of an exception. Selections from William Carlos Williams’ poetry, specifically “The Orchestra” (reading) and “Theocritus: Idyl I—A Version from the Greek” from his own The Desert Music and “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower” (reading), provide the text for the choir. Reich cites a particular section of “The Orchestra” as being thematically critical: “Say to them: / Man has survived hitherto because he was too ignorant / to know how to realize his wishes. Now that he can realize / them, he must either change them or perish.” Williams wrote this poem in the wake of the nuclear bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, so desert applies both to the New Mexico testing grounds for the weapons and the lifeless aftermath from the fallout. Reich also cites two other deserts—the Sinai, where the Jews entered after their exodus from Egypt, and the Mojave desert in California, which Reich had visited on several occasions. Much like Different Trains and Tehillim, The Desert Music brings together strands of history, culture, and personal experience.

Yet Reich makes another key point in the liner notes: “All pieces with texts [have] to work first simply as pieces of music that one listens to with eyes closed, without understanding a word. Otherwise, they’re not musically successful, they’re dead ‘settings.’” More so than Tehillim or Different Trains, The Desert Music fulfills this requirement. This point is no slight against those other pieces, rather an important recognition that their texts are harder to ignore, especially the spoken extracts of Different Trains. I would further argue that Different Trains’ narrative accounts need to be hard to ignore. The poetic tracts of The Desert Music, on the other hand, aren’t the principle layer of the compositions. They add to the initial listening experience, which covers the promise of the American West, the foreboding darkness of Hiroshima, and the struggles of the Sinai. Returning to the cited WCW passage, the idea of realizing wishes and then having to change them applies in all three contexts in different ways, but with similar potential outcomes. The Desert Music is thematically charged, yes, but in a way that continues to open up avenues of conversation.

The jury is still out on whether The Desert Music join Reich’s 1970s compositions in my heavy listening pile. The emphasis on the chorus, whether singing the Williams poetry or wordless melodies, is a major difference from the pulsing usage of human voice in Music for 18 Musicians, and goes against my usual preferences, although I do enjoy it here. Going back to the idea of elemental Reich vs. thematic Reich, The Desert Music seems too full, too symphonic to properly compare with the elemental minimalism of Music for 18 Musicians. With the application of a theme, even a flexible, conversationally oriented theme, the overall scope expands. Whether that scope fits as many listening scenarios as my favorite Reich pieces is doubtful, but I don’t feel close to being done with The Desert Music.

Note: the 2001 CD pressing of Tehillim / The Desert Music by Cantaloupe Music features a different performance of each piece.

|