|

I realized two things as I spun the advance leak of Mogwai’s live album, Special Moves, over and over: first, that I’d have to bite the bullet and order the deluxe 3LP+CD+DVD set; second, and more importantly, that for all of my frustrations with the band not consistently reaching its transcendent high-water marks, Mogwai is still one of my favorite groups. Sure, I’d kill for an album of peaks like “Mogwai Fear Satan,” “2 Rights Make 1 Wrong,” and “Helicon One”—or pay $60 for the limited edition of a live record containing those songs—but virtually every release in their catalog is worthy of attention.

Mogwai bristles at being designated “post-rock,” holding dear to the idea that they’re just a rock band like the Stooges or Black Sabbath, but few bands have dictated the course of post-rock as much as they have. Perhaps this angst over the genre is due to motifs they originated becoming clichés in lesser hands and then critically re-applied back to their newer work—a point which isn’t entirely off-base—but whereas other prominent post-rock bands have splintered, run out of creative energy, or dropped off my radar completely, Mogwai has persevered. Even if they disdain the genre, it doesn’t deter from their ability to write wonderful songs within it.

Unlike my Sonic Youth Discographied feature, I will cover the vast majority of Mogwai’s various singles and EPs, since they don’t have fifteen full-lengths to cover. This post starts with Ten Rapid and 4 Satin, their first two proper releases.

Ten Rapid: Collected Recordings 1996-1997 – Jetset, 1997

Highlights: “Helicon One,” “Helicon Two,” “Summer”

Low Points: “I Am Not Batman,” “End” is padding

Overall: Few of my favorite bands boast this flattering of an infancy.* Hum’s Fillet Show is a false start; good luck hearing any of those songs in their sporadic reunion sets. My Bloody Valentine’s early material explored gothic tendencies, not guitar bliss. Juno’s earliest demos were wisely kept under wraps, since those solo-heavy recordings would have lumped them in with countless Seattle grunge bands. Early Shudder to Think is faster, sure, but lacks any subtlety. So why is Ten Rapid worth hearing when those albums are for pure die-hards only?

The most simple answer is that their initial blueprint remained true. Each successive full-length adds more compositional depth, but the guiding principles of the band were sound at the beginning. Going back to a minimal song like “Helicon Two” or “A Place for Parks” isn’t an alienating experience like unearthing Fillet Show—they still feel like Mogwai songs. There are brief interludes of vocal slowcore, but they make sense within the surroundings, even if that approach was largely abandoned. They also had the presence of mind to turn these scattered seven-inches into a viable album, leaving behind the weakest of the lot.

Ten Rapid’s sequencing is one of its strengths, abandoning the chronological release dates of its eight previously released songs (closing track “End” is “Helicon Two” played backwards—Murder by Death did the same trick on Like the Exorcist but with More Breakdancing, back when they were called Little Joe Gould and were more influenced by Mogwai than Johnny Cash) in favor of a regular album flow. “Summer” begins with hazy foreshadowing of the song’s soaring guitars, crashing crescendos, melodic chimes, and hyperactive drumming. “New Paths to Helicon (Part Two)” strips things down to a gentle drumbeat and a wandering guitar line, with the occasional gurgle of bass beneath. “Angels vs. Aliens” twists the pummeling textures of “Summer” into a tense rhythmic knot. The ambient “I Am Not Batman” and lovely “Tuner” present Mogwai as a slowcore band more akin to Codeine and Low than Slint. (The best comparison for “Tuner” might be Pavement’s “Strings of Nashville.”) “Ithica 27 ϕ 9” finds the natural transition between the lulls of “Helicon Two” and the rage of “Summer” in its quiet-loud-quiet structure. “A Place for Parks” is a mellow jam leading into the collection’s triumphant high-point, “New Paths to Helicon (Part One).” The instrument switching is key, since Stuart Braithwaite plays the loping, melodic bass line and Damon Aitchison contributes the blurry swaths of guitar noise. What strikes me about “Helicon One” (and why it’s still a regular in Mogwai set lists) is its simplicity—everything contributes to that gradual curve upward, nothing sticks out. As such, it’s remarkably easy to get lost in the mist.

The only previously released Mogwai song not to make the cut for Ten Rapid was the b-side to the “Tuner” single, “Lower.” Its angst-driven rock and jarring transitions have false start written all over them, so you weren’t missing much.

Perhaps my fondness for Ten Rapid was contingent upon getting into Mogwai close to the ground floor. There’s less distance between the early material here and Young Team than say, 2006’s Mr. Beast. If you’re used to the polish of the later works, perhaps the lo-fi charms of “Tuner” and “Helicon Two” won’t affect you, but it amazes me how well Ten Rapid has held up to thirteen years of post-rock development and scrutiny.

* I recognize how many exceptions there are to this statement, especially from the last decade, but the 1980s and 1990s seem more populated with ragged beginnings and false starts than brilliant opening statements. Also, I'd rather continue to be interested in a group's development than gradually lose interest as they lose inspiration (See: Interpol).

4 Satin EP – Jetset, 1997

Highlights: “Superheroes of BMX,” the first five minutes of “Stereodee”

Low Points: “Stereodee” sure goes on for a while

Overall: The 4 Satin EP is a confounding bit of Mogwai lore. Early pressings from Jetset Records, like the one I own, had an unintended song (“Guardians of Space”) and an alternate, lesser take on “Stereodee.” If your CD has four tracks, it’s the misprint. It’s no surprise this release was later collected along with No Education = No Future (Fuck the Curfew) (which has its own curious history) and Mogwai EP as EP + 6. While I highly recommend tracking that compilation down to prevent any potential frustration, I’ll discuss the EPs separately.

If you have the proper version of 4 Satin, a sampled conversation and drum machine intro lead off the understated “Superheroes of BMX,” one of my favorite Mogwai songs. Two sighing keyboard chords alternate as guitar arpeggios and live drums filter into the mix. The melancholy turns tense as squalls of feedback arc over the wavering lead guitar, but the song never loses its grounding emotion. It’s a loose, rambling song, lacking the precision of their later work, but that combination of anxious noise and insistent melancholy covers up any flaws.

“Now You’re Taken” marks the group’s first collaboration with Arab Strap singer Aidan Moffat. It drifts more gingerly than most Arab Strap songs, but the general feel is the same—Moffat’s deeply accented voice ruminating over a relationship gone sour. (If you need a starting place for Arab Strap, I recommend Philophobia.) The closing lines “And I should tell you that I adore you / But I’m sure that I’d just bore you” nail the mood of this particular song. It’s not as memorable or melodic as Moffat’s other Mogwai guest appearance on Young Team’s “R U Still in 2 It,” but it’s a nice warm-up.

The thirteen-and-a-half minutes of “Stereodee” close out 4 Satin with a very long, very loud bang. The first three minutes are the melodic build-up, a compelling combination of jangly chords and churning acceleration, but then the wall of white noise hits and sticks around until the twelfth minute, when an inexplicable dance beat emerges. If you’ve seen Mogwai—or any number of comparable post-rock or noise-rock groups—picture the song at the end of their set that closes with guitars-against-amp feedback as the members gradually leave the stage. That’s “Stereodee.” It’s a lot more viscerally exciting when your fingers are jammed against your ear drums in the rock club, trying futilely to maintain your hearing for the next day. At home you can just turn it off after five or six minutes, which is what I usually end up doing.

Finally, the fuck-ups. “Guardians of Space” is a grinding rocker with a repetitive riff and garbled vocals in the background. Think of it as a dry run for Young Team’s far superior “Katrien.” The alternate take on “Stereodee” doesn’t do the song justice. It’s three minutes shorter than the proper version, lacks the proper build-up to the white noise apocalypse, and overdoses on the flanger pedal for the intro guitar riff. I can’t fathom how angry Mogwai must’ve been when they found out both of these songs were in stores.

Provided you find the right version (or just bite the bullet and get EP +6), 4 Satin’s a rather rewarding side street in the Mogwai catalog. Two of these songs will reappear later in alternate versions (“Superheroes of BMX” on Government Commissions, “Stereodee” as “Quiet Stereo Dee” on Travels with Constants), but I prefer the versions here. All three songs are worth hearing, but “Superheroes of BMX” is the keeper.

|

46. Ween – The Mollusk LP – Plain, 2010 [1997] – $15.20 (Newbury St. Newbury Comics, 4/17)

Mark Prindle’s review of Ween’s Chocolate and Cheese summarizes quite well my uncertain feelings on the group: “All of a sudden, it's no longer evident whether the Weeners are kidding or not.” And yet Prindle, having reviewed all of Ween’s discography and given high marks to most of their LPs, should be someone who gets Ween without qualification, following up that comment with “And, of course, they weren't - Ween are honestly attempting to emulate different forms of music that they happen to enjoy.” As someone who’s dabbled with Ween but never gone full-bore into their catalog, I can agree to a certain extent with both of Prindle’s statements. It’s frequently unclear whether Ween’s more serious songs are simply mimicking the seriousness of the source material they ape or if these songs are genuinely cathartic for the group (or both!), but I’ve never doubted their ability to accurately recreate the sound of a given genre, group, or era. Where I can’t agree with Prindle is in the concrete statement that they weren’t kidding. Sometimes they are, sometimes they aren’t, sometimes the joke’s in the music, sometimes the joke’s in the lyrics, sometimes the joke is in both.

My personal hesitation on fully embracing Ween on their shifting, uncertain terms is how clearly they push against my usual listening habits. Sure, I grew up with the Dead Milkmen, whose often childish sense of humor was rooted in less refined attempts at genre-hopping (the James Brown-skewering “RC’s Mom” from Beelzebubba and the Dick Dale homage “Surfin’ Cow” from Bucky Fellini being two of their more memorable genre excursions). Most groups I like nowadays are quite serious. My favorite album, Juno’s A Future Lived in Past Tense, takes itself dead seriously, even with the “I’m sorry you’re having trouble… goodbye” note at the end of the LP. Stars of the Lid’s And Their Refinement of the Decline has a few humorous song titles and its austere compositions contain occasional moments of levity, but such moments never dominate. Groups like Frightened Rabbit and The Narrator include self-effacing humor in their lyrics, but that humor comes from a personal place. I am overwhelmingly drawn to emotional, cathartic music. If it’s funny, great, if it’s not, that’s fine, too. These groups take both their music and the process of making it quite seriously. In contrast, Ween takes the process of making their music quite seriously, but the music itself fights tooth-and-nail against this seriousness. It’s a confounding listening experience, I tell you.

I understand why people often herald The Mollusk as Ween’s finest outing, the group themselves included. Unlike many Ween albums—Chocolate and Cheese, White Pepper, La Cucaracha—the group’s typically scattershot stylistic approach is reined in to a certain extent on The Mollusk. It’s not as single-minded as its 1996 predecessor, Twelve Golden Country Greats, but the prevailing whiffs of late 1960s folk and 1970s prog-rock focus the songwriting. That doesn’t mean they write fourteen of the same song—good luck mistaking the children’s musical opener “I’m Dancing in the Show Tonight” with the fluttering prog of “The Mollusk,” the electro-punk of “I’ll Be Your Jonny on the Spot” with the circular melodies of the folky “Mutilated Lips,” the Irish sea shanty “The Blarney Stone” with the New Romantic leanings of “It’s Gonna Be Alright”—and that’s just (most of) the first side. The second side emphasizes 1970s prog more, especially the faux-epic “Buckingham Green,” which launches into a remarkably self-important and then adds timpani and strings. These stylistic threads tie the songs together so that the genre-hopping makes sense.

If I’ve learned anything from thinking deeply about Ween, it’s that you really shouldn’t think deeply about Ween. It’s a simple process of learning to enjoy the apparently serious songs and the apparently joking songs alike, since the more Ween I hear, the more I realize there’s no clear distinction between the two sides. I may still be a few Ween shows and spins of albums like The Pod and Pure Guava away from ever spouting the company line of “Ween is the greatest band alive,” but I can certainly listen to it for what it is: very serious joking.

|

The Pupils – The Pupils LP – Dischord, 2002 – $3.20 (Newbury St. Newbury Comics, 4/17)

As an extension of Daniel Higgs and Asa Osborne’s main group, Dischord mainstays Lungfish, the Pupils are to a large extent argument-proof. Opinions may vary on the quality or importance of the Lungfish’s minimal, repetitive punk-rock and mystic incantations, but the chances that any of those opinions will affect the group’s gradual evolution are nil. You’re either on board or you’re not. You are far more likely to change than they are. I speak from experience on that last point, having looked upon a few stray Lungfish songs as a curious offshoot of DC punk rock back in high school, only to have The Unanimous Hour finally click a few years ago. It’s not that they don’t change—there’s a noticeable arc to their career, starting out with the aggressive punk of Necklace of Heads and Talking Songs for Walking, progressing to the honed precision of Indivisible, and finally to the garage minimalism of Feral Hymns—but this evolution never feels haphazard or forced. If anything, I’d call it erosion, not evolution, since tendencies are stripped away, the flesh made bare over the course of time.

Another terminology correction: earlier I called The Pupils an extension of Lungfish, not a side project, and this specification is critical. At no point during The Pupils did I get the sense that Higgs and Osborne were out to try something overtly new with this name. It’s Lungfish without a rhythm section. While many listeners would be upset at this specification, hoping for a different take on Lungfish’s signature combination of minimalism and mysticism, it makes perfect sense to me. There are certainly gentler moments than usually appear on Lungfish LPs, specifically “It’s Good to Have Met You” and “I Will Remain Human for Another Day,” but these are just as wonderfully confounding as any Lungfish song. The former has an atypically romantic notion in “It’s good to have loved you my sweetheart / It’s good to hope that we should never have to part,” but it fits into a cycle of bonds recalling Lungfish’s “Hallucinatorium.” "I Will Remain Human" reaffirms the oddity of Higgs’ lyrics with “We’re hand in hand at the horizon / We gird our loins for teleharmonizing” even as it circles back on the seemingly loving territory of “It’s Good to Have Met You.” There’s plenty of other quirks to be found, like “Witness the Sidewalk Weeping Pools of Martian Brine,” which is just long enough to recite the title, but The Pupils never feels shoddy or tossed-off.

Perhaps I’m giving Higgs/Osborne/Pupils/Lungfish too much leeway because of their idiosyncratic nature, but it’s honestly refreshing to hear an album and not have my critical impulses emphasize what I would’ve had them do differently. (I leave such impulses to Daniel Higgs’ solo work, where my critical impulses say “Stop playing the mouth harp already.”) The Pupils does exactly what I expected and yet it’s not limited to my expectations, a typically Lungfish mind-bender.

|

R.E.M. – Green LP – Warner, 1988 – $5

Green feels like it should be a double dip, considering how many times “Pop Song 89,” “Stand,” and “Orange Crush,” but I never got the CD growing up and I’ve somehow avoided pulling Green out of an LP dollar bin to this point. I blame the insistent “Stand”: a cheery pop song that might be more enjoyable if I hadn’t heard it a thousand times on MTV and the radio growing up. (I had to stop myself from going on a lengthy tangent on how long it’s been since I’ve listened to FM radio for music.) “Stand” isn’t nearly as irritating as “Shiny Happy People,” but the song’s key change and escalation of its circular lyrics are best avoided.

Perhaps I’d put too much stock in the singles being stylistic barometers for Green, but the album features little of the perkiness of “Stand” or the R.E.M.-as-U2 seriousness of “Orange Crush,” and reasonable doses of the polished hooks of “Pop Song 89.” In short, it sounds more like an IRS-era R.E.M. album than I expected, just more open, less closed-off. “Turn You Inside-Out” comes the closest to the machine-gun strafing of “Orange Crush” with its hard rock overtones and reversed reverb on the snare hits (a decidedly ’80s production trick I could live without). “Get Up” follows up lead track “Pop Song 89” with a similar dose of energetic rock. The most evocative songs on the album do a tricky double move—sounding larger than their IRS predecessors and yet still intimate among their immediate surroundings. “You Are the Everything” is an emotional, minimal folk song that expands their bounds without reaching “Everybody Hurts” universality. “I Remember California” is a downer of a rocker, lacking the angst of “Orange Crush” or the pep of “Stand,” but it still feels big. The untitled closer features an instrument swap between Peter Buck and Bill Berry (according to Matthew Perpetua’s write-up on Pop Songs), which might explain why the song feels so delightfully off-the-cuff.

Green isn’t particularly cohesive, especially on the second, “Metal” side, which veers between arena rock, intimate folk, and college rock too wildly. I would certainly enjoy “Hairshirt” more if the cringe-worthy titular word weren’t part of it. “Turn You Inside-Out” is Monster forced. I’d love to tie these flaws together into a thesis on how R.E.M. crumbled under the pressure of their major-label debut, but increase in scope isn’t the biggest issue. Green simply has some weak material weighing it down, which could’ve happened on any label.

26. R.E.M. – S. Central Rain (I’m Sorry) EP – IRS, 1984 – $5

Considering that I haven’t given the proper attention to a number of the proper R.E.M. albums—a few of the good ones, too, not just the post-Berry albums—buying a 12” EP for Reckoning favorite “So. Central Rain (I’m Sorry)” is a bit of a curious move, even by my standards. (Don’t expect this to turn into a R.E.M. Discographied feature: Matthew Perpetua already wrote about every R.E.M. song and I have no interest in hearing Reveal or Around the Sun.) Much like a few New Order and Joy Division singles I’ve picked up, I simply liked the cover art.

”So. Central Rain (I’m Sorry)” is a superb song, featuring Michael Stipe’s elliptical storytelling in the verses and the spare, emotional “I’m sorry” chorus. His wordless vocals on the outro are downright harrowing—not something I’d expect from the lead single on an album, but wonderfully evocative in their own way. The b-sides are amusing enough, if non-essential. “Voice of Harold” is an alternate take of Reckoning’s “7 Chinese Brothers” with alternate lyrics. Those lyrics? The liner notes to a gospel album laying around the studio. It gets genuinely funny when Michael Stipe assumes a dramatic, almost Elvis-esque affectation, but it’s not likely to get funnier with more listens. A pleasant cover of the Velvet Underground’s “Pale Blue Eyes” finishes off the flip. I wish I could compare it to the original, but I’ve never gotten into VU. Someday I’ll sit down with their albums and truly absorb them, but for now, it’s just another note on my musical to-do list.

|

Pavement – Watery, Domestic EP – Matador, 1992 – $7 (Newbury Comics in Harvard Square, 4/6)

Back in March, Pavement reissued their five full-lengths along with the Watery, Domestic EP at introductory prices to (presumably) capitalize on their upcoming reunion tour. Given that you could initially get all six LPs direct from Matador for the post-Ticketmaster price of one seat for their Boston show in September—a whopping $50—it’s hard to knock the vinyl pricing. The reunion tour, sure, that’s going to fund Nastonovich’s horse-racing gambling habits, Spiral Stairs’ next five solo albums, and Malkmus’s courtside seats for the Portland Trailblazers, but the recent proliferation of $20 to $25 reissues from Neutral Milk Hotel, the Smiths, and New Order makes a $10 LP a welcome change of pace. Terror Twilight aside, they’re all must-have albums.

My issue with these reissues is how they fit into an ongoing string of Pavement reissues from Matador. Their first four full-lengths have each received the 2CD set treatment and by all accounts these sets are near perfect. As someone who tracked down all of the group’s EPs and singles, it’s almost criminal that the new generation of Pavement fans can spend $15 and get all of the relevant b-sides, plus any extra demos, live recordings, or alternate takes from that album’s time period. Even with my current vinyl-only attitudes, getting the Nicene Creedence edition of Brighten the Corners on 2CD for $15 instead of the 4LP set for $65 was a no-brainer. (Editor's note: But $25 turned out to be feasible for it!) The ultimate question is how many times I can go to the well for a band I admittedly love. Take Watery, Domestic. I bought the original CDEP. The songs were included on the Slanted & Enchanted 2CD set. (You could argue—quite accurately—that I didn’t buy the Slanted 2CD for the songs I already owned, rather for the additional material, but I still bought it.) This vinyl repress makes the third time that I’ve paid for these songs in some capacity. “Texas Never Whispers” is on number four, having been included in the What’s Up Matador compilation, an essential part of my indie rock education. Pavement is making Morrissey and the Smiths twitch with envy.

So why did I pick up Watery, Domestic yet again? Beyond my desire to no longer be excited upon finding Ambergris’s self-titled LP, I can’t help but maintain my affections for what might be the best statement in Pavement’s catalog. Bridging the gap between the buzzing lo-fi hooks of Slanted and the mid-fi maturity of Crooked Rain, Watery, Domestic’s remarkable ease makes its four superb songs sound almost tossed-off. What strikes me about three of these four songs—“Lions (Linden)” mostly sticks with high school football—is how slippery they are. They glide along, throwing out perfect lines like “So much style that it’s wasting” without ever sounding glib. “Shoot the Singer (One Sick Verse)” is a melancholic, emotional song that still belies any attempt for a concrete reading. “Well I’ve seen saints, but remember / That I forgot to flag ’em down” and “Slow it down! Song is sacred!” each hold such resonance, but tying them to the rest of the song simply isn’t an easy task. There’s a logical counter-argument here that Malkmus lacked coherence for his elliptical poetry, but that’s what made these songs so appealing. It’s also what I miss so much in his songwriting nowadays. The gap between Watery, Domestic and “Harness Your Hopes” and “Carrot Rope” wasn’t as noticeable at the time, but Malkmus switched from sounding like he wasn’t trying at all to sounding like he was trying very, very hard. I’ll take the nonchalance for the third time, please.

|

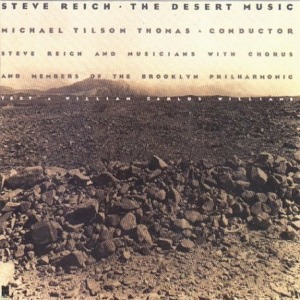

Steve Reich – The Desert Music LP – Elektra, 1985 – $6.50 (Mystery Train, 5/16

I find myself sticking with a few of Steve Reich’s pieces more than others, specifically Music for 18 Musicians, Octet / Music for a Large Ensemble / Violin Phase, and Six Marimbas, but it wasn’t until I picked up The Desert Music that I understood why. Those pieces were all composed in the 1970s and are formative explorations into minimalism. There isn’t a prevailing theme to Music for 18 Musicians, it simply goes. Those compositions set up the rules, the boundaries, and the elements for Reich’s later releases.

His major compositions in the 1980s—Tehillim, The Desert Music, and Different Trains specifically, for the simple reason that I own and have heard them—apply topical themes to these elemental templates. Tehillim evokes Reich’s Jewish heritage; The Desert Music follows William Carlos Williams’ poetry into the very idea of deserts; and Different Trains juxtaposes Reich’s frequent train trips in 1939–41 with those of European Jewish children headed off to Nazi death camps during the Holocaust. It’s heady, important stuff, especially Different Trains, and I commend Reich for taking this direction. He could have easily been content to explore the form’s more distant corners with different instrumentation (like Pat Metheny’s guitar performance of Electric Counterpoint that follows Different Trains on the LP) or plied his trade on film soundtracks, but bringing an emotional, personal, and historical resonance to his compositions is far more rewarding. More recently his 2006 release Daniel Variations focused on Daniel Pearl, the Jewish-American journalist beheaded by a Pakistani militant group in 2002.

The disconnect between Reich’s elemental 1970s compositions and his thematically charged 1980s compositions comes down to ease of listening. When I reviewed Octet / Music for a Large Ensemble / Violin Phase last year, I called it “remarkably flexible music,” noting how I frequently listened to it while working, driving, or reading, not just in active-listening scenarios. Whether Different Trains works in these passive contexts is up for debate, but it’s difficult to ignore the thematic arc of that release. The Kronos Quartet’s stuttering strings are just as disconcerting as the conversation snippets. Tehillim faces a different hurdle: I don’t share Reich’s Jewish upbringing. While that didn’t stop me from enjoying Mogwai’s “My Father My King,” I suspect that Tehillim is a far richer experience with the proper background.

On the surface, The Desert Music isn’t much of an exception. Selections from William Carlos Williams’ poetry, specifically “The Orchestra” (reading) and “Theocritus: Idyl I—A Version from the Greek” from his own The Desert Music and “Asphodel, That Greeny Flower” (reading), provide the text for the choir. Reich cites a particular section of “The Orchestra” as being thematically critical: “Say to them: / Man has survived hitherto because he was too ignorant / to know how to realize his wishes. Now that he can realize / them, he must either change them or perish.” Williams wrote this poem in the wake of the nuclear bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, so desert applies both to the New Mexico testing grounds for the weapons and the lifeless aftermath from the fallout. Reich also cites two other deserts—the Sinai, where the Jews entered after their exodus from Egypt, and the Mojave desert in California, which Reich had visited on several occasions. Much like Different Trains and Tehillim, The Desert Music brings together strands of history, culture, and personal experience.

Yet Reich makes another key point in the liner notes: “All pieces with texts [have] to work first simply as pieces of music that one listens to with eyes closed, without understanding a word. Otherwise, they’re not musically successful, they’re dead ‘settings.’” More so than Tehillim or Different Trains, The Desert Music fulfills this requirement. This point is no slight against those other pieces, rather an important recognition that their texts are harder to ignore, especially the spoken extracts of Different Trains. I would further argue that Different Trains’ narrative accounts need to be hard to ignore. The poetic tracts of The Desert Music, on the other hand, aren’t the principle layer of the compositions. They add to the initial listening experience, which covers the promise of the American West, the foreboding darkness of Hiroshima, and the struggles of the Sinai. Returning to the cited WCW passage, the idea of realizing wishes and then having to change them applies in all three contexts in different ways, but with similar potential outcomes. The Desert Music is thematically charged, yes, but in a way that continues to open up avenues of conversation.

The jury is still out on whether The Desert Music join Reich’s 1970s compositions in my heavy listening pile. The emphasis on the chorus, whether singing the Williams poetry or wordless melodies, is a major difference from the pulsing usage of human voice in Music for 18 Musicians, and goes against my usual preferences, although I do enjoy it here. Going back to the idea of elemental Reich vs. thematic Reich, The Desert Music seems too full, too symphonic to properly compare with the elemental minimalism of Music for 18 Musicians. With the application of a theme, even a flexible, conversationally oriented theme, the overall scope expands. Whether that scope fits as many listening scenarios as my favorite Reich pieces is doubtful, but I don’t feel close to being done with The Desert Music.

Note: the 2001 CD pressing of Tehillim / The Desert Music by Cantaloupe Music features a different performance of each piece.

|

|

I find myself caring less and less about specific labels nowadays, betraying the days when label catalogs were a primary source of recommendations. So many of the labels I closely followed in the 1990s—Touch & Go, Matador, DeSoto, Dischord, OhioGold, Mud—have closed up shop, slowed their release schedules to a crawl, or changed focus. Medications recently commented on how difficult of a time they were having booking a tour in support of their new Dischord LP Completely Removed (a wonderful album—buy it now). Amid specifics like trying to get opening slots without being tour-long openers, the lack of a booking agent, Dischord’s non-interventionist nature, and the baffling disconnect between Faraquet fans and Medications fans comes the starkest reality: even a prominent, respected label like Dischord carries less weight nowadays. I remember when groups like Durian and Bald Rapunzel fell through the cracks because they couldn’t get on Dischord. Now that frame of reference is almost negligible. (Exceptions apply, of course—it seems like label recognition now applies more to no-fi punk, noise, and psych-rock than straight indie rock.) In its place is an increased emphasis on first-hand marketing techniques like Facebook, MySpace, YouTube and the hopes that the music itself will become the recommendation, since file-sharing removed the difficulty of tracking down most albums.

The Mylene Sheath is a bit of a throwback to those old days. The only reason I bought this Giants LP was because they pressed it. As I mentioned for the review of Constants’ The Foundation, The Machine, The Ascension, they go balls-out on their packaging. Neither They, the Undeserving nor The Four Trees is as elaborate as the Constants set or Junius’s The Martyrdom of a Catastrophist (which I’ve ogled in Newbury Comics a few times), but each release scratches a similar collector’s itch: Giants get a limited pressing of white vinyl; Caspian gets a full-color gatefold and nice half-white, half-pilsner vinyl. I’m not a Mylene Sheath completist by any means, but beyond the consistently impressive packaging, I know to expect post-rock or something that appeals to people who like post-rock. That description may be too limited to squeeze in the dramatic Cure-like lurching of Junius (any good label has exceptions to their stylistic accords), but I’d wager that I’m not far off. After all, the Mylene Sheath isn’t a geographically limited label like Dischord or Mud. True to form, both Giants and Caspian are post-rock groups. I’ll even venture to say that they’re both a certain kind of post-rock band, so bear with me as I establish what exactly that means.

I tend to think of post-rock in two interconnected ways: tiers and phases. There are three tiers: the top is the ideals, the second is the trendsetters, and the third is the followers. There’s the strict definition of doing making music against rock conventions, exemplified by bands like Talk Talk and Bark Psychosis in the ideals tier. These groups are difficult to emulate since there’s no defined aesthetic or songwriting blueprint to appropriate. The second tier is comprised of groups like Slint, Tortoise, Mogwai, and Godspeed You Black Emperor that help define the various branches of the genre of post-rock—Slint’s the source of the math-rock trappings and dynamic arcs, Tortoise is the source of the jazzy inflections, structural tinkering, and lack of angst, Mogwai’s the source of melodically geared instrumentals, and Godspeed’s the source of the collage-based twenty-minute epics with strings. (Boy, do post-rock groups love adding strings and other alternate instrumentation.) Argue for Sigur Rós, Do Make Say Think, or Explosions in the Sky, but those four bands would be on my Mount Rushmore of modern post-rock. Third, there are the groups that exist immediately within this genre without expanding its boundaries. They’ll argue about it—see the Mercury Program’s steadfast insistence that they’re separate from this discussion—but you know a post-rock band when you hear one. There’s a wide range of quality within this third tier—plenty of derivative bands are also thoroughly enjoyable—but it’s by far the largest. Truly original ideas are hard to come by.

Next, from a chronological perspective, there have been four major phases of post-rock: the Slint phase, the Tortoise phase, the Godspeed phase, and the Explosions in the Sky phase. (Sorry Mogwai, you came at the tail end of the Slint phase, but at least your collective face was still carved into theoretical rock. I also emphasize major, since there have been plenty of secondary phases.) The Slint phase was the least distinct, since groups were also influenced by the second-generation post-hardcore leanings of Rodan and Drive Like Jehu (which thereby lends itself to the dudes-only math-rock), but the emphasis on time-signature changes, dynamic shifts, and harmonic chimes goes back primarily to Slint. This phase lasted until the mid 1990s, although Mogwai kept it alive later in the decade with “Like Herod.” The Tortoise phase was the least prevalent, since you need some actual chops to appropriate jazz moves. (It’s also the least interesting—even a presumably likeable band like Pele was bland as hell on record.) This phase didn’t last particularly long—I’d say 1998 to 2001 or so—since it was so goddamn boring. (Tortoise excluded until It's All Around You.) The Godspeed phase removed some of those barriers—if you played viola in your high school orchestra, you were in—and opened up the compositions’ length and removed the emphasis on structural integrity. Its height was from 2000 (with the release of Lift Your Skinny Fists) to 2004, when their influence began to wane (although Yndi Halda's 2007 "EP" Enjoy Eternal Bliss certainly owes GYBE royalties). Finally, the Explosions in the Sky phase is the most distinct. “But EITS sound an awful lot like Slint and Mogwai,” you say. That’s entire true, but because of EITS’s high profile from soundtrack appearances and touring, they’re the go-to reference point for so many recent post-rock bands, not Slint or Mogwai.

What Explosions in the Sky did was simplify the template: two guitars, bass, and drums equals emotional instrumental rock. They made it look easy. You can’t understate the importance of that point. Kids can pick up the usual instruments, not worry about picking a singer, and play with a single goal in mind—creating an emotional arc. Because that’s the end goal, audiences are quick to respond. Win-win. It’s hard not to get wrapped up in post-rock shows since they’re so dramatic, especially hard when you haven’t tired of the trick. Explosions in the Sky’s true gift to post-rock was figuring out how to reach people who hadn’t tired of the trick. Soundtrack appearances in Friday Night Lights (both the film and the superior TV series) certainly did that. Touring endlessly helped. This logic is not a knock against EITS as a group—they put out two memorable LPs, Those Who Tell the Truth Shall Die… and The Earth Is Not a Cold Dead Place, they’re a great live band—but their influence has watered down the genre.

All of this leads me to these two LPs I picked up. Both groups are in the third tier and in the Explosions in the Sky phase. The specifics may differ—Giants write shorter, more compact songs; Caspian utilizes heavier riffs and ambient lulls—but it’s hard not to think of Explosions in the Sky as the primary reference point, albeit not the sole influence. If you’re dedicated to the genre, this specific branch of the genre, then you should certainly check Caspian, at least. Labels like the Mylene Sheath allow me to dabble in the guitar-rock side of post-rock with consistent results. Yes, I’ve exhausted myself with the likes of Red Sparowes and God Is an Astronaut, choosing (like many others) to focus on the drone/ambient side with Stars of the Lid, Eluvium, and Tim Hecker or the electronic side with Fuck Buttons, Errors, and Port-Royal (which is facing its own level of exhaustion), but sometimes the simple pleasures are the most rewarding.

28. Caspian – The Four Trees 2LP – The Mylene Sheath, 2007 – $5 (Déjà vu Records, 3/5)

The main two reasons why I hadn’t previously picked up any of Caspian’s LPs is that they’re a much more exciting live band and I’ve routinely come away from their recorded material wanting more. I’ve seen them a handful of times around Boston, but the one I remember most clearly was a performance at P.A.’s Lounge in Somerville. Much like the Explosions in the Sky show I caught at Café Paradiso in Urbana, this Caspian performance benefited greatly from the small size of the venue. I felt like I was right on top of their enormous sound. When they turned on their flashing strobe lights during the crashing, start-stop riffs of The Four Trees’s “Brombie,” it was downright disorienting. Putting epic songs in a small room is a recipe for success. They’re good in a more cavernous space like the Middle East Downstairs, but the effect is diminished. Is it any surprise that recording this material further lessens the effect? How many albums can replicate that experience?

That isn’t to say The Four Trees doesn’t capture some level of this rush. Epics like “Moksha,” “Crawlspace,” “Brombie,” and “Asa” eat up huge chunks of the runtime with their dramatic arcs, punishing riffs, and bursts of triumph. “White Space” recalls Hum’s heaviness and Tim Lash’s racing leads. The combination of thunderous drums, slide guitar leads, and acoustic guitar treatments gives “Book Nine” both texture and power. Those six tracks over forty-one minutes should be the envy of most modern post-rock bands. They have moments of beauty, bursts of ferocity, lulls for recharging, and a deft sense of timing.

However, it’s an hour-long album, and The Four Trees would have benefitted from some pruning, pardon the pun. I could do without a few of the mellow soundscapes, like “The Dropsonde,” “Our Breathe in Winter,” and “The Dove,” especially since the last two are inexplicably sequenced next to each other. “Reprise” is essentially a hidden track with another blasting crescendo waiting at the ending, perhaps indicting the acoustic outro of “Asa” as insufficient for an album closer. Given that The Four Trees is Caspian’s debut LP after the compact You Are the Composer EP, perhaps pulling out all of the stops was the logical next move, but they’re simply more interesting as a bruising post-rock band than a gentle ambient outfit. Hopefully their third album (sophomore release Tertia smoothed out the edges for too much blurred strumming) plays more to their strengths, giving me more moments like “Brombie” in their excellent live sets.

29. Giants – They, the Undeserving LP – The Mylene Sheath, 2008 [2007] – $5 (Déjà vu Records, 3/5)

Similar to Caspian’s The Four Trees, Giants’ They, the Undeserving is the group’s first full-length following a debut EP (specifically a 2006 self-titled, four-song demo). Unlike Caspian, Giants didn’t bite off more than they could chew. Undeserving avoids the editing problems of The Four Trees. These six songs span thirty-five minutes, locking together as one long piece with three barely perceptible movements (“Birth,” “Plague,” and “Rest,” calling to mind the tripartite nature of Constants’ The Foundation, The Machine, The Ascension). Once I put this record on the turntable, I know I’m going to listen to the whole thing.

The problem comes after the record’s over. Sure, the ten-minute-long closing track “Withered Life: Communal Rhythm” is impressive, developing its melodic themes from its introductory military-roll drumming to its intersection of swooping and floating guitar leads and finally to the album’s last crescendo. Past that song, however, there’s a lot of pleasant Explosions in the Sky post-rock that fails to make a lasting impression. “Steps in Static Progression” has a staccato guitar part more typical to the post-emo of the Jealous Sound than contemporary post-rock, so at least it’s doing something different. Too many of these songs don’t take chances, don’t step out from their apparent inspirations.

Giants have a follow-up LP, 2008’s Old Stories, which was recently pressed on vinyl by Cavity Records. Part of me is interested in hearing whether Giants spent as much time on the details of their songwriting for that one as they did on the outline for They, the Undeserving, but I’m in no rush. I’d rather be teased with greatness than appeased with competence.

|

Medications – Completely Removed LP – Dischord, 2010 – $11 (4/10 Dischord Mail Order)

The DC scene seems averse to giving out such honors, but Devin Ocampo needs a lifetime achievement award. Having first come on my radar as the drummer for Smart Went Crazy’s excellent Con Art, Ocampo soon resurfaced as the singer and guitarist for the math-rock trio Faraquet. People usually reference their lone full-length, The View from This Tower, and with good reason (it is awesome), but it was the “The Whole Thing Over” b/w “Call It Sane” single that impressed me the most. Math-rock is notoriously afraid of hooks, but Ocampo coupled the nimble guitar figures in “Call It Sane” with some brain-burrowing melodies. (It’s included on their Anthology 1997-1998 LP. Go get it.) His post-Faraquet output has been similarly impressive. Ocampo and Faraquet drummer Chad Molter formed Medications, granting Molter his own switch from the kit to (primarily) bass duties. Medications' self-titled debut EP and 2005 LP Your Favorite People, All in One Place pull Faraquet’s style in new, often opposing directions, both with more open hooks and knottier rhythms. Ocampo returned to drumming duties for Mary Timony’s excellent Ex Hex and The Shapes We Make LPs, the latter including Molter on bass. Ocampo’s involvement was exactly what Timony’s solo career needed—Ex Hex was her most memorable album since Helium’s The Magic City, grounding her songs with muscular, decidedly DC rhythms. Along with Molter, he’s now a full member of Beauty Pill, having contributed to their 2005 full-length The Unsustainable Lifestyle. Have I mentioned his production skills? I certainly will when I track down the Imperial China full-length, Phosphenes. Just give the guy a trophy already.

Three things stand out to me about Ocampo’s career: 1. He’s versatile; 2. He’s a team player; 3. He’s consistently great. When drummer/guitarists are mentioned, it’s usually Dave Grohl and Damon Che (of Don Caballero / Thee Speaking Canaries), but Ocampo’s success on both fronts is just as impressive, even if it’s grossly overlooked. Unlike Che (I’ll give Grohl some leeway for stepping in for Killing Joke’s 2003 self-titled LP), who dominates any project he’s involved in, Ocampo’s non-frontman contributions make those bands, those records better without turning them into the Devin Ocampo show. That isn’t to say Ocampo’s the only reason why Smart Went Crazy improved so much between Now We’re Even and Con Art, or why Mary Timony got her mojo back with Ex Hex, but some credit must be given. After all, Ocampo hasn’t been part of a disappointing album. When the advanced press on Completely Removed promised something notably different from Your Favorite People, I wasn’t even slightly concerned. I was excited.

This advertised difference is apparent in the line-up. Drummer Andrew Becker departs, replaced in part by “swingman” Mark Cisneros, but the bigger development is emergence of Chad Molter as a co-frontman. Ocampo and Molter trade off vocals on most tracks on Completely Removed, in practically every permutation (“Rising to Sleep” involves a trade-off on the syllable level). Unlike other multi-singer bands, there’s no sense of needing to balance the two egos, since Ocampo and Molter have been friends and collaborators long enough not to worry about such things. Instead, democracy dominates. Molter’s softer voice contrasts well with Ocampo’s ability to hold a note with unwavering intensity. I now recognize a key issue with the lifetime achievement award I just doled out to Devin Ocampo. I can’t help but feel guilty in not including Chad Molter when they’re bound so firmly at the hip. Molter’s the unsung hero of this group and this album—these songs come off as musical conversations between the two (with the occasional witty retort from Cisneros) and quoting only one side of the conversations seems silly.

Becker’s absence is felt more in the instrumental balance of the songs. Gone are the tense rhythm-driven workouts like “Twine Time” and “Opinions” from Your Favorite People. Such time signature changes and fretboard tangles have mellowed, gaining notable ease on the airy “Brasil ’07,” which trades complex chord changes for vibes and horns. As much as I love the intensity of “Surprise!” and “Pills” from Your Favorite People, that album isn’t the easiest to sit through from start to finish. In contrast, Completely Removed is a natural driving-around album for summer. The dominant elements of the songs are usually melodic guitar leads or vocal hooks, not intricate, forceful rhythms or finger-twisting guitar riffs. It’s not that those elements are completely gone—“Home Is Where We Are” reminds me of an updated take on the beloved “Call It Sane,” “Long Day” intertwines arpeggios with aplomb, and “Kilometers and Smiles” brings out some gnarly ’70s funk leads—but they fit within the songs.

This switch results in Completely Removed being deemed more “pop,” which is both true and limiting. Yes, the album is lighter, hookier, and more approachable than either of Medications' previous releases—all welcome changes. I doubt I’ll find a more repeatable stretch of songs than the opening quartet of “For WMF,” “Long Day,” “Seasons,” and “We Could Be Others” this year. Yet my most basic idea of pop music—as something geared to appeal to a broad audience—doesn’t quite fit here. Medications’ songs are more polished and catchier, but they’re still remarkably cerebral. Take the title track, for example. Ocampo sings, “I’m removed / If not hidden from view… completely removed” and “I wish that I was open / and I wish that I did care,” lines that seem to explore his/their acknowledged distance from the crowd. “We Could be Others” calls back to these lines with its chorus of “We could be open / We could be sober / We can be others I know,” but ends it with “It’s too late / It’s too long.” That’s the tension of Completely Removed: making steps toward the middle, being comfortable with your new position, yet still recognizing that you don’t quite belong. That’s not the sole topic of these songs—“Brasil ’07” is quite the love song for Ocampo’s wife—but I can’t hear “as my human crimes wear thin on you” in “Long Day” without pondering the need to specify “human.”

Being too cerebral for true pop standing shouldn’t be viewed as a negative. Too often I struggle to explain why exactly I go off the beaten path to find new music, especially when I’m talking with people who are content to stick to the pop songs they know and love. But Completely Removed is the perfect example of the rewards of this pursuit. Its combination of hooks and smarts won’t lose its luster once the initial rush has gone away, since the lyrics and arrangements are so richly layered. This is why I follow musicians like Devin Ocampo and Chad Molter, why I’m continually impressed by the ways they evolve as musicians and adapt to fit new surroundings. It’s also why I wouldn’t mind seeing at least one of these guys get an enormous trophy for their efforts.

|

|

Programming note: I've been stuck on a few albums that, quite frankly, I don't have much to say about, so for the foreseeable future, I'll be going out of purchased order. It is safe to say I am the only one who cares about breaking my internal rules. It is also safe to say that updates will be coming much, much faster now.

17. Sonic Youth – Goo 4LP – Goofin', 2005 [1990] – $28 (Newbury St. Newbury Comics, 2/2)

If you haven’t seen my write-up on Goo as part of my Sonic Youth Discographied feature, I direct you there first. This post will focus on everything else you get in this four LP box set: twenty additional tracks, full-color sleeves, over-enthusiastic liner notes, late-onset street cred.

First, the unreleased tracks. “Lee #2,” shockingly enough, is a Lee Ranaldo song, specifically a lackadaisical one with a melodic chorus and half-baked verses. It’s more reminiscent of his songs from Washing Machine and A Thousand Leaves than “Mote.” “That’s All I Know (Right Now)” is a cover of the Neon Boys, a pre-Television band featuring Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine playing proto-punk. Sounds like proto-punk! “The Bedroom” is an energetic, if somewhat sloppy live instrumental. Thurston makes a joke about what you do when your mom’s a skinhead at the beginning. I won’t ruin the punchline. “Dr. Benway’s House” is a go-nowhere instrumental. Finally, “Tuff Boys” is some vintage Sonic Youth messin’ around. Imagine if they got tired of feedback like Dave Knudson of Minus the Bear got tired of finger-tapping all the time. The first two songs are worth hearing, the next three could have been left in the vaults.

Next, the demos. Sonic Youth had never done proper demos before Goo, which doesn’t surprise me a whole lot; they seemed far more likely to tinker with songs in practice or live than in the studio. (This presumably changed when they built their own studio.) The liner notes mention how Goo’s demos had floated around before the final production was completed, so some fans prefer the rough cuts to the polished versions. I understand that preference—if I had a time machine, I’d go to 1996 and get Hum to record “Comin’ Home” when they first wrote it and it had jagged edges—but these demos make me appreciate the major-label polish and editing of the real deal. The guitars sound muddy, the bass is too prominent, the drums lack clarity—they’re demos, alright. Plus, as you can tell from runtimes like 6:37 for “Dirty Boots” and 7:49 for “Corky (Cinderella’s Big Score),” they’re Sonic Youth demos, with extra messin’ around. Little thing amuse me: how much better the bridge is on the final version of “Tunic,” how Thurston messes up the vocal melody for “Dirty Boots,” how Kim Gordon’s more restrained delivery on the demo of “My Friend Goo” is almost palatable. Bigger changes are less interesting, like the nearly nine minutes of “Blowjob (Mildred Pierce),” which tacks on six minutes of aimless riffing to the already tiresome proper version, or the addition of an instrumental version of “Lee #2.” It’s a different way to hear Goo, but I hesitate to call much of it better.

After those bonus tracks and demos, what more could you want? More bonus tracks? Sure! The cover of the Beach Boys’ “I Know There’s an Answer” from Pet Sounds recalls Frank Black’s cover of “Hang onto Your Ego” from Frank Black, since it’s the alternate take of “I Know There’s an Answer.” The verses and melodies are the same, the chorus changes, and Sonic Youth opts for wobbly feedback over Frank Black’s new wave sheen. Naturally, the liner notes explain how “We wanted to do the original lyrics to it… We wanted to do it as ‘Hang onto Your Ego.’ But someone discouraged us from doing that.” Conspiracy theories, go! “Can Song” is an alternate take of “The Bedroom.” “Isaac” is another forgettable instrumental. Finally, there’s a “Goo Interview Flexi,” in which Thurston Moore does his best to sound like a beat poet / late night DJ in describing the inspirations for his songs, Kim Gordon sounds both cutesy and spacey. Did I learn much from that interview? Of course not.

The liner notes are quite thorough: a 12x12” full-color booklet with a lengthy contextual essay from critic/friend Byron Coley and a short perspective from Geffen A&R guy Mark Kates, who helped bring the band onboard. The former has considerably more credibility as a former writer for Forced Exposure and a friend of the band, but I prefer the latter’s more to-the-point recap of the era, since Coley gushes feverishly when describing the songs. On “Tunic”: “[Kim and J. Mascis’s] harmonies have a feel not unlike that of Corinthean leather.” On “Dr. Benway’s House”: “It sounds like hot Nova wind blowing across the Moroccan desert, pushing around a whole lot of jeeps and camels.” (Counterpoint from Lee: “It’s basically a 16-track tape loop.”) On “Can Song”: “Whatever you call it, those guitars build a big damn half-pipe stretching way up into the sky.” Maybe Coley’s always this enthusiastic, but it’s strange when the band members are, for the most part, far better at viewing the album in hindsight.

As for the late-onset street cred, this box set of Goo will take up nearly an inch of real estate on your vinyl shelf. Couple it with the similar box sets for Daydream Nation and Dirty and Sonic Youth has dramatically increased the value of the neighborhood. There’s a distinct possibility that these records will make recommendations to their neighbors, like “It would be pretty cool if you turned into a long out-of-print proto-punk single” or consolations like “Don’t worry, you’re bound to have a Carpenters-esque hipster revival one of these days.” Plus you get a whole lot of material for just a few bucks more than the single-LP reissues of their earlier records would cost you.

|

I Need That Record! The Death (or Possible Survival) of the Independent Record Store is filmmaker Brendan Toller’s love letter to those indie record stores and investigation of what brought about their downfall. Given the amount of time and money I spend in record stores, this documentary would seem to be right up my alley, but there’s a curious disconnect in the film’s intended audience. If you’ve followed music for the last 15 years, it will come across as a tedious mix of preaching to the choir and beating a dead horse. If you haven’t followed music for the last 15 years, you’re less likely to check out a documentary called I Need That Record.

Let me run through some of the major topics of discussion from the first hour of the film: major radio stations are bad, Clear Channel is bad, big box stores are bad, major-label executives are bad (and dumb), manufactured pop is bad, MTV is bad, indie record stores are good, and the old “Is Napster / file-sharing good or bad?” debate. The well-trodden “why” of indie record stores’ downfall is considerably less compelling than the reasons for their success, which usually come through interviews with musicians like Ian MacKaye, Glenn Branca, Lenny Kaye, Mike Watt, and Thurston Moore (who, like Chunklet mentioned, is obligated to appear in every documentary). Noam Chomsky even appears, giving the film a rare moment of critical insight when he expands on the film’s emphasis of the community appeal and value of the stores. I feel for the (mostly former) record store owners interviewed for the film, but only Newbury Comics’ Mike Dreese recognizes that such stores need to adapt their business models to survive. The others are exasperated and angry, but not proactive.

I’m not surprised I Need That Record has garnered enthusiastic praise. Toller’s heart is in the right place, and few music lovers will argue against the premise that independent record stores are a good thing. My final point may come across as overly harsh—perhaps like Dreese’s indictment of the tired business models of his brethren—but I Need That Record feels like a student paper. It recaps the major developments, pulls quotes from primary and secondary sources, and makes some conclusions from its findings. Sure enough, I Need That Record started out as Brendan Toller’s senior thesis at Hampshire College. By itself that’s an astonishing achievement—I certainly never interviewed Noam Chomsky for a paper—but I’d be more intrigued by a graduate-level film, one that contributes something new to the discussion instead of just recapping it.

|

|