12. Shearwater – Rook LP – Matador, 2008 – $4.50 (Norwood, MA Newbury Comics, 1/24)

I took a chance on this Shearwater record for a few reasons: first, it’s on Matador; second, it was cheap; third, they’ve toured with bands I enjoy (Wye Oak and The Acorn); and fourth, I figured my wife might like it. Had I waited a few months, I would’ve added Shearwater frontman Jonathan Meiburg’s appearance on this exceptional Wye Oak cover of the Kinks’ “Strangers” for the Onion AV Club. In spite of all of these promising justifications, I should’ve heard Shearwater first.

I’ll be blunt: Meiburg’s mannered delivery rubs me the wrong way. It’s suited to early 1970s prog-rock like King Crimson, in which case his precise falsetto and reedy bellow would feel right at home. A more contemporary name that comes to mind is Talk Talk’s Mark Hollis, whose controlled phrasing and melodic flourishes occasionally present the same irritation, if not the same eventual dismissal. I’ll admit it: I like J. Robbins’ everyman voice and virtually every voice that resembles it. That’s my default.

It’s not that Rook is bad album. The occasional bursts of crashing guitar on “On the Death of the Waters” and “Century Eyes” recall a manicured version of Neil Young. “Rooks,” “Leviathan, Bound,” and “The Hunter’s Star” incorporate horns, chimes, strings, and piano with a deft hand. But my qualms with Meiburg’s vocal mannerisms extend to the music. There’s an underpinning of theatricality to these songs that occasionally erupts, like the invigorated delivery of “We'll sleep until the world of man is paralyzed” on “Rooks.” The ornithology-inspired lyrics provide a unique perspective, but there’s no chance my brain will allow me to appreciate them.

If you enjoy mannered deliveries and lingering theatricality, Shearwater is worth checking out. If those phrases make you retract a bit from the monitor, heed my warning. Even though I love Shudder to Think’s Pony Express Record and learned to love Talk Talk, some challenges are too great.

13. Let’s Active – Afoot LP – IRS, 1983 – $1.50 (Norwood, MA Newbury Comics, 1/24)

Let’s Active are one of those “I’ve heard of them, but I’ve never heard a note of their music” groups that I’ll check out if the price is right. (See also: Dumptruck.) And for $1.50, the price was right. I mostly know them as contemporaries of R.E.M. in the 1980s college rock / jangle-pop scene, since singer/guitarist Mitch Easter produced early R.E.M. albums like the Chronic Town EP, Murmur, and Reckoning and they shared the IRS imprint. (Mitch Easter later produced Pavement’s Brighten the Corners and Helium’s No Guitars EP and The Magic City.) He certainly produces good music, but does he write it?

That verdict hasn’t come in, but I certainly got the genre tags right. The first side of Afoot sticks firmly with jangly college rock, with the winning “Every Word Means No” demonstrating the best combination of clean guitars, crisp drumming, and chipper, melodic vocals. Let’s Active spreads out a bit on side B with less success. The female vocals and new wave textures of “Room with a View” cite Blondie. The enthusiastic “In Between” could almost be mistaken for a Go-Go’s song. “Leader of Men” has a twitchy new wave bass line and an out-of-character squealing guitar solo. I suspect these new wave elements gradually filtered out of their sound on future recordings, since the jangle-pop/college rock side was more in vogue in their crowd. Afoot will hit the spot if you’re fond of jangle-pop from the 1980s or 1990s, but I suspect you’d be better off grabbing “Every Word Means No” and the better material from their later releases.

|

|

Along with the next few entries, these two self-titled LPs come courtesy of a 50% off used vinyl sale at the Norwood, MA Newbury Comics, the only location to carry it. They certainly had a lot of overpriced '80s wax to clear out, but fortunately there were some keepers in the lot.

10. Cluster & Eno – Cluster & Eno LP – 4 Men with Beards, 2007 [1977] – $6 (Newbury Comics in Norwood, 1/24)

I knew when I picked up Old Land, the compilation made from Cluster & Eno’s two LPs, that I would end up buying at least one of the original albums. I did not anticipate it happening so soon, but the price being right on the reissue pressing of the first of Cluster & Eno’s collaborations expedited the process.

What impressed me so much about Old Land was that the compilation held together as an album, with the synth-heavy side A deriving exclusively from 1978’s After the Heart and the comparatively somber side B primarily pulling from this 1977 collaboration. As expected, Cluster & Eno sticks with the somber ambience of those songs. Of the five songs new to me, three explore an ambient combination of subtle background synths and twinkling foreground piano. “Ho Renomo” and the short, nearly classical “Mit Samaen” are quite lovely. With its pulsing drum beat, “Selange” is the bridge to the remaining two new-to-me songs, “Die Bunge” and “One,” which branch out into new terrain. “Die Bunge” finds a cantering electronic pulse, like a futuristic cow-poke striding slowly into the horizon, and “One” predicts Eno’s later foray into world music on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts with droning sitar and African percussion. These new songs are all worthy additions, but I’ve gone back to the closing track, “Für Luise,” most frequently. It features an alien cooing sound that’s at once friendly and eerie.

In hindsight, it feels like Eno took the lead on the first collaboration, and then Cluster’s electronic tendencies came to the forefront on After the Heat. If you’re interested in the Cluster side of things (or one of Brian Eno’s best vocal songs, “The Belldog,” which I seem to twitter about every week), start with After the Heat. If you’d prefer to stick with Brian Eno’s ambient explorations, Cluster & Eno is one of his better efforts in that field.

11. Burial – Burial 2LP – Hyperdub, 2006 – $6.50 (Newbury Comics in Norwood, 1/24)

When I went through best-of-the-decade album lists, Burial’s Untrue was one of the most frequent albums to appear that I hadn’t yet heard and had some desire to check out. (If you want to read that as a slight against Animal Collective, please, go ahead.) To be entirely honest, I’d missed the entire UK garage / dubstep / grime scene. My first, admittedly filtered taste was Burial’s collaboration with Four Tet on 2009’s “Moth” / “Wolf Cub” EP, but finding this marked-down copy of Burial’s first, self-titled album seemed like a good invitation to dip my toes in the pool.

It doesn’t take long to survey Burial’s instrumental palette: anxious rhythms, subwoofer-rumbling bass pulses, chopped-up vocal samples, unnerving synth noises, crackling surface noise, and the occasional affecting keyboard melody make up the bulk of these tracks. The lone exception is “Spaceape,” featuring Spaceape, which incorporates the British MC’s moody monologues. That song is the biggest indicator of my initial point of comparison—which I fully expect to embarrass people better-versed in electronic music than I am—which was Tricky’s early trip-hop albums, specifically the ghostly remnants of a track like “Overcome” from Maxinquaye. To be entirely frank, the specific reference point doesn’t matter as much as the idea that Burial is the ghostly remnants of it.

The highlights of the album demonstrate just how effective this dark, chilling mood can be. “Distant Lights” could be the sound of a club from a block away. Its chopped-up R&B vocals trim the fat, leaving only the choicest cuts. “Forgive,” based on a sample of Brian Eno’s glorious “An Ending (Ascent)” from Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, could very well be the inversion of Eno’s own space exploration, choosing instead to peer up at the moon through gray smog. “Pirates” has flashes of energy, like car alarms triggering in the distance. I’m stuck on this idea of spatial distance playing a huge part in Burial’s songs, since each track feels like it’s been carved away from a larger original work, pulled away from an wider view. My mind keeps going to what’s absent.

It’s unlikely that this site will turn into This Month in Dubstep/Grime anytime soon, but as an uninformed glance into one of electronic music’s more prominent developments, Burial is a solid offering. I’ll certainly check out Untrue down the line.

|

9. Fuck Buttons – Tarot Sport 2LP – All Tomorrow’s Parties, 2009 – $18 (Newbury Street Newbury Comics, 1/22)

When I heard Fuck Buttons’ widely acclaimed debut LP, Street Horrrsing, I was more excited by what it hinted at, not what it was. The insistent synth bass and tinkling effects of “Sweet Love for Planet Earth” and the trance-inducing build-up of “Bright Tomorrow” foreshadowed more polished efforts. Remixes of “Sweet Love” and “Colours Move” by Andrew Weatherall and Mogwai respectively demonstrated how excellent Fuck Buttons’ material could be when removed from the rhythmic clutter and haphazard yelling of Street Horrrsing. Presumably Fuck Buttons themselves felt inspired by these remixes, since they tasked Weatherall with producing the follow-up album, Tarot Sport.

Pardon me if you were disappointed by the lack of abrasive noise on Tarot Sport—I know some people were—but there aren’t many cases when I feel like a group delivers exactly what I was hoping for with a follow-up LP. It’s an absolute thrill. (Other examples: Bottomless Pit’s Congress EP and Tungsten74’s Binaurally Yours.) I knew Tarot Sport wouldn’t be entirely free of the noise fetish from Street Horrrsing, and “Rough Steez” and “Phantom Limb” provide a more controlled take on that style, so I’m willing to bring them along for the ride to break up the string of epic jams.

When I say exactly what I was hoping for, I’m selling Fuck Buttons short, since I did not anticipate just how great “The Lisbon Maru,” “Olympians,” and “Flight of the Feathered Serpent” (in particular—the whole album is superb) would be. The forthcoming comparison may also sell them short, since Mogwai is one of the group’s noted influences, but these songs reminded me more of hearing “Mogwai Fear Satan” for the first time than anything else released since 1997. Compositionally they pull off the same trick—anchoring epic songs with basic melodies, then sending them flying into space—but do so with different instrumental palettes. Plenty of post-rock bands cribbed the wrong notes from “Mogwai Fear Satan,” incorporating flutes into their crescendo rollercoasters, but that’s just a lazy facsimile (likely driven by the fact someone in the group played flute in high school) focused on the details, not what made the original great. In the vaguest, most infuriating terms possible, “Mogwai Fear Satan” sent me somewhere else. It’s that feeling Fuck Buttons captures, not the road signs or the exit ramp to the eventual destination.

Each song captures it with a different tack. “The Lisbon Maru” offsets the propulsion of its electronic pulses and martial drumming with a hint of resignation before letting that feeling disappear amidst a cloud of distorted keyboards. “Olympians” hints at the slow-motion triumph of Vangelis’ theme to Chariots of Fire, even though its BPM is club-ready. “Flight of the Feathered Serpent” drops out midway through its escalating climb to demonstrate the potency of its background counter melody—the one you might have missed lurking under the pounding beats. These are specific moments of transcendence—a word I don’t use lightly—bound to the overall arcs of their songs.

Where do Fuck Buttons go from here? Who knows. I don’t have a specific destination in mind. Mogwai’s career presents the most logical option: gradually trading transcendent wonder for increased instrumental prowess and compositional confidence, thereby creating solid albums with fewer moments of awe-inspiring brilliance. Plenty of options are worse than longevity and stature. All I hope for right now are more moments like “Flight of the Feathered Serpent”—figuratively, not literally, of course.

|

8. Ritual Tension – Expelled LP – Fundamental, 1989 – $1 (Davis Square Goodwill, 1/19)

Talk about a shot in the dark. Ritual Tension’s third LP stood out from the usual array of Streisand, Denver, and Diamond LPs in the dusty bins of the Davis Square Goodwill basement. I expected punk/hardcore from the band name, album title, and cover art, but a quick check of the Trouser Press guide indicated that they were contemporaries of groups like Sonic Youth, Swans, and Live Skull in the NYC noise-rock scene of the mid-1980s. Goodbye, one dollar. I don’t think I’d endured enough early Sonic Youth at this point to truly fear what Ritual Tension might offer, but fortunately, Ritual Tension isn’t as enamored with the art side of the scene.

Ivan Nahem’s crazed vocals bring my biggest reference point for Ritual Tension: David Yow of the Jesus Lizard. Nahem isn’t as gleefully unhinged as Yow—who is?—but he comes close at times, howling over discordant, misshapen guitar riffs. Closing track “Watching a Diver” highlights these vocals by dropping out the aggressive backdrop for the first half of the song, likely recalling the uneasiness of Swans (a group I’ve never spent time with—please ridicule me in the comments section). Ritual Tension owes some debt to the wonky riffs of Sonic Youth’s Confusion Is Sex, but my inclination of hardcore punk wasn’t entirely off, either. It’s a record that makes some sense coming out of NYC in 1989, but would make far more sense coming out of Chicago in 1996.

|

|

These two LPs came from New Paltz, NY’s Rhino Records, a store I hadn’t visited in several years. It brought back fond memories of loading up on cheap CDs in high school.

6. Colin Newman – Commercial Suicide LP – Enigma, 1986 – $12 (1/17 Rhino Records)

The title of Colin Newman’s fourth solo album implies a detour from the nervy, antagonist post-punk of A – Z and Not To to less hospitable terrain, but the stylistic shift to electronically equipped chamber pop isn’t nearly as severe as what Wire fans came to expect with Graham Lewis and Bruce Gilbert’s art-damaged Dome albums. Yet I still agree with Colin Newman’s warning; Commercial Suicide marks a drastic left turn in compositional orientation. There’s plenty of weird, alienating textures on A – Z and Not To, but they’re essentially guitar rock records. Commercial Suicide is decidedly not.

More specifically, Commercial Suicide isn’t a Wire record. Both A – Z and Not To featured Wire drummer Robert Gotobed and a few songs originally intended for their follow-up to 154. (Compare the Wire version of “Safe” from Turns and Strokes to Newman’s own version from Not To; the difference between the thrashing snarl of the former and the wearied restraint of the latter is huge.) Those two albums picked up where Newman’s songs on 154 left off. Once Wire reformed in 1985, Colin Newman’s solo output branched off, making Commercial Suicide the first Newman solo album to truly feel distanced from Wire.

(A brief covering-my-bases note: this discussion excludes Provisionally Entitled the Singing Fish, Newman’s Brian Eno-inspired album of short instrumentals. It’s a pleasant diversion for those people who just can’t get enough of Music for Films, but every time I put it on, I wish Newman would sing over the tracks like he with “Fish One” on the CN1 EP, rechristening it “No Doubt.”)

This distance is explored on the opener, “Their Terrain,” (MP3) a fanfare for Wire’s concurrent return that forgoes guitars and percussion for both real and synthesized symphonic swells. It’s the most memorable track here by a fair margin, demonstrating how well Newman’s melodic instincts (“Outdoor Miner,” “The 15th,” “& Jury”) translate to chamber pop. Other keepers include “But I…,” highlighted by an atypically open chorus of “I have waited for so long / I,” and “I Can Hear Your… (Heartbeat),” which features background vocals from Newman’s now wife Malka Spiegel (who still collaborates with her husband in Githead). These highlights stand out clearly, since too many songs flounder in a propulsion-less slog from the album’s distaste for percussion.

Yet Commercial Suicide’s critical flaw is its reliance on 1980s synthesizers masquerading as orchestral flourishes. I tend to skirt the issue of “dated” recordings, since almost every record is tied to its historical context by its production values and/or compositional signposts, but it’s impossible to hear Commercial Suicide without thinking two things: 1. This record came out in the mid 1980s 2. This record would sound so much better if the ’80s synths were actual instruments. Strings are certainly present here, but not exclusively. Imagine Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock with obvious synth tones—would it hold the same critical reverence? I doubt it. Commercial Suicide needs to sound grand, not canned.

Newman’s next solo album, It Seems, bridges the gap between these eras to some extent, relying on sequencers for less chamber-oriented pop. (It’s just as dated, if not more so.) It’s not, however, as brave or compelling of a switch as Commercial Suicide was. For all of this album’s flaws, it’s impossible for me to hear the marvelous “Their Terrain” or “But I…” and not appreciate the chances Newman takes in switching from post-punk to chamber-pop or marvel at the success he has with such a different form. Sure, I still wonder what it would sound like with the Laughing Stock treatment, but Commercial Suicide provides detailed notes for that mental re-recording.

7. Seam – “Days of Thunder” + 2 7” – Homestead, 1991 – $4 (1/17 Rhino Records)

It still blows my mind that Mac McCaughlin of Superchunk / Portastatic / Merge Records fame was Seam’s drummer when they started out. The band went through numerous line-up changes during its eight-year run, but starting out in North Carolina with Mac on drums is the biggest head-scratcher. “Days of Thunder” is their debut single, featuring the same line-up from 1992’s Headsparks (bassist Lexi Mitchell joining Seam mainstay Sooyoung Park) and sharing one song, “Grain.” The a-side does the lugubrious Seam template quite well—mumbled vocals, slowed-down tempos, buzzing guitars, bass hum, and those gloriously reticent melodies. “Grain” picks up the tempo, adding more jangle to the guitars, although it’s not as upbeat as the album version.

The cover of the Big Boys’ “Which Way to Go” fills out side B nicely with female vocals carrying a lilting rendition of the tune. It’s borderline twee, dropping Mac’s drums out for an occasional shake of a tambourine, but Seam was particularly good at stretching the logical boundaries of its melodic indie rock sound. I certainly expect this song was a head-scratcher for any Bitch Magnet fans hoping that Seam picked up where Ben Hur left off.

I’ve uploaded the “Days of Thunder” single along with seven other out-of-print songs from Seam singles here. The understated cover of David Bowie’s “Heroes” is quite nice.

|

5. Loose Fur – Loose Fur LP – Drag City, 2003 – $10 (RRRecords, 1/7)

Wilco isn’t mentioned much around these parts, mostly in passing like here, here, here, and here. Is it a grudge? A blood feud? Sadly not. Much like Radiohead, there’s a notable disconnect between my modest interest in the group and their overwhelming critical backing. I enjoy both OK Computer and Summerteeth, but neither album ranks among my absolute favorites. I find their respective turn-of-the-century postmodern epics, Kid A and Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, to be intriguing and periodically rewarding, but not revelatory. In the face of 10.0s from Pitchfork, moderate appreciation is wildly contrarian.

Since then, my take on the bands’ respective releases has diverged. Viewing Amnesiac and The Ghost Is Born as extensions of their predecessors to varying degrees, both bands have gone back to basics with Hail to the Thief / In Rainbows and Sky Blue Sky / Wilco the Album, stripping away some of the postmodern artifice that fans and critics alike drooled over. This switch hasn’t done much to make me care more about Radiohead—attachment has always been the foremost issue with them, going back to my high school malaise with The Bends—but it’s helped with Wilco. Scoff if you must, but the clean, intersecting lines of Sky Blue Sky’s “Impossible Germany” appeal to me more than the structural tinkering of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot’s “I Am Trying to Break Your Heart.” Does that make Sky Blue Sky a better record than any of the three which preceded it? No, but there’s less baggage for me to worry about.

All of this Wilco discussion is crucial for how I approach Loose Fur, an album full of such baggage. Whereas most listeners would be stoked about how the combination of the Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy and Glenn Kotche and producer / musician / muse Jim O’Rourke inspired the postmodern turn on their beloved Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, I’m wary. If anything, I’m more intrigued by how Loose Fur ties to O’Rourke’s superb Insignificance, which also features Tweedy and Kotche. Here’s the convoluted timeline for the three albums:

Summer 2000: Loose Fur is recorded.

Late 2000 to Early 2001: Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is recorded. Jim O’Rourke is brought on to mix the album.

Summer 2001, presumably: Insignificance is recorded.

September 2001: Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is leaked to the public.

November 2001: Insignificance is released.

April 2002: Yankee Hotel Foxtrot is released.

January 2003: Loose Fur is released.

In retrospect, this roll-out makes sense, since O’Rourke’s solo album didn’t weigh on the potential impact of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot, but Loose Fur had the potential to lessen the impact of Glenn Kotche’s percussive tricks on YHF. It does, however, position Loose Fur as a bit of an afterthought in this process, which is unfair to an otherwise interesting record.

The first side of Loose Fur does its own gradual roll-out. Opener “Laminated Cat” is a weirded-out version of Wilco’s “Not for the Season,” a mellow Tweedy vocal melody that snowballs into a mammoth boogie riff for its extended outro. O’Rourke follows up with “Elegant Transaction,” a ’70s folk-pop ballad that could’ve fit on Insignificance with its delicate acoustic guitar melodies and O’Rourke’s usual acidic lyrics (“A connection all the same / Like urine loves cold slate”). “So Long” is the first song that distinctly Loose Fur. O’Rourke’s lyrics certainly fit in with his usual modus operandi—“If I said I love you, I was talking to myself”—but the scraggly guitar and clanging percussion is a noticeable step away from the steadfast listenability of Insignificance. Over its nine minutes, “So Long” eventually casts aside the stray threads for a traditional “La-da-da-da” outro with piano, acoustic guitar, standard drumming, and hints of that wonky guitar. Its best moments occur during the transition between these phases, when the traditionally beautiful acoustic guitar pushes through the skronk of the electric guitar.

Side B continues this give-and-take between Tweedy and O’Rourke’s day jobs and Loose Fur’s emergence, but lacks the same level of payoff. “You Were Wrong” is a lackadaisical Tweedy song that could be easily slotted in as a Wilco b-side if not for a touch of dissonance. “Impression Totale” is an inconsequential instrumental that segues from a folky introduction to a noisy guitar build-up. “Chinese Apple” is a Tweedy-sung track that hints at the spaciousness of Yankee Hotel Foxtrot midway through, but mostly sticks with its pretty folk melodies. It’s the highlight of his songs here, giving more leeway for O’Rourke’s affinities for ’70s AM pop.

It doesn’t surprise me that Pitchfork’s take on Loose Fur is essentially opposite to mine, in how they preferred the Tweedy material on side B to the O’Rourke-heavy A side. They also prefer Yankee Hotel Foxtrot to Insignificance, so the former album is their reference point, whereas the latter is mine. Casting aside the reference points for a minute, let’s take stock: there are two great O’Rourke songs, two solid Tweedy songs, and a couple of forgettable songs. I’ll live with that. Could Loose Fur have used an editor’s touch? Sure. Almost all of these songs run past five-and-a-half minutes, giving them a definite three-guys-jamming feel. It often feels more like a collection of cast-aside solo material than a merger of the minds. I’ll certainly check out their 2006 follow-up, Born Again in the USA, to see if those elements have been fixed, but if I happen to encounter a few more Insignificance outtakes, that’ll be fine, too.

|

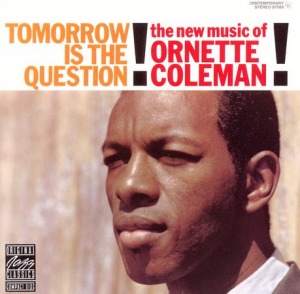

3. Ornette Coleman – Tomorrow Is the Question! LP – Contemporary, 1959 – $15 (RRRecords, 1/7)

I decided at the beginning of this year that the biggest remaining hurdle for my appreciation of jazz (don’t worry, I cringed typing that phrase just as much as you cringed reading it) is the nature of my listening. Instead of dabbling with a wide variety of performers and styles, I’ve opted to focus my efforts on a few key musicians I already know I like. Why I hadn’t done this earlier is beyond me—I can’t imagine thinking “I like 1990s DC rock, so I’m going to buy one album from each band and not worry about following up secondary material from favorites like Jawbox or Shudder to Think.” Such a process ignores understanding how an artist or band changes from album to album.

Ornette Coleman’s third album, The Shape of Jazz to Come, is one of the jazz albums that truly clicked for me on first listen, so it made sense to follow him down the rabbit hole. Tomorrow Is the Question! is Coleman’s second LP, trimming down his debut Something Else!!!! in both members and exclamation points. Gone is contractually obligated pianist Walter Norris, a notable departure of the chord foundation for Coleman’s trade-offs with Don Cherry’s cornet. The rhythm section temporarily dropped drummer Billy Higgins for Shelly Manne (who later appeared on Tom Waits’ Small Change and Foreign Affairs) and featured Percy Heath on bass for side A and Red Mitchell for side B.

These line-up changes underscore what I expected from Tomorrow Is the Question!: it’s a much more traditional album than The Shape of Jazz to Come. Traditional doesn’t necessarily mean bad—there are some lovely compositions on side A and the bright, optimistic mood is infectious—but it’s not as exciting as Coleman’s later works. Coleman and Cherry frequently hint at the free-jazz structures of Shape with their racing interactions, most notably on album highlight “Endless,” but the rhythm section, especially on side A, constricts this freedom. The liner notes mention Manne’s excitement to play without the usual boundaries, but he might have needed a few more albums to fully adapt to this style. There’s no other way to put it: the lack of Higgins and future Coleman standby Charlie Haden on bass is noticeable. I want songs to change course more often, to threaten to come completely apart.

Surely this line works its way into every review of the album given its title, but the most interesting aspects of Tomorrow Is the Question! are those that point to Ornette Coleman’s future recordings. It makes perfect sense that Coleman would progress somewhat gradually—if only two warm-up albums even qualify as gradual—into the free-jazz of The Shape of Jazz to Come. Perhaps the most astonishing fact is that Tomorrow and Shape were recorded two months apart in 1959 and released that same year. How many rock groups release multiple albums in the same year (Robert Pollard, sure) and display marked change from one to the next? (There goes Pollard’s furious hand-waving.) I’m certainly interested in seeing whether Coleman kept evolving at such a frantic pace.

4. Ornette Coleman – Science Fiction LP – Columbia, 1972 – $9 (RRRecords, 1/7)

I paired Tomorrow Is the Question! with Ornette Coleman’s 1972 LP Science Fiction in part to marvel at the expected juxtaposition. Unlike Tomorrow, which I correctly assumed would be a more traditional precursor to The Shape of Jazz to Come, I had no specific ideas of what Science Fiction would offer. Between the hazy, spooky cover art and the decidedly out-there album title, Science Fiction could’ve blasted Coleman off to Sun Ra’s lost planet of space-jazz, taken root in Miles Davis’ jazz-fusion, or found its home with Herbie Hancock’s jazz-funk. I wouldn’t have been surprised by any of these outcomes, yet none of them is remotely accurate.

A look at the personnel would’ve grounded my expectations. Yes, two songs feature vocals from Indian-born singer Asha Puthuli and one features spoken word from poet David Henderson, but regular Coleman contributors like Don Cherry, bassist Charlie Haden, and drummers Ed Blackwell and Billy Higgins appear on every track. Science Fiction is never too far from the free-jazz I’m used to hearing from Coleman, but it’s how specific songs and performers stand apart from this foundation that’s intoxicatingly great.

Asha Puthuli’s soulful vocals on “What Reason Could I Give” and “All My Life” are superb. Her voice intertwines with Coleman and the other horns on each song, pulling off the trick marvelously on “All My Life.” Billy Higgins sounds like a man possessed drumming on “Civilization Day.” Charlie Haden’s jaw-dropping solos in “Street Woman” and “Law Years” find tones and textures beyond the usual fingerboard workouts, sounding almost like drones during the former song. Poet David Henderson’s contribution to the title track couples with swarming horns and a baby crying for a profoundly bizarre listening experience. “Rock the Clock” adds texture from Coleman’s violin and Dewey Redman’s musette, which I assume is what sounds like a wheezing electric organ. “The Jungle Is a Skyscraper” lets Coleman, trumpeter Bobby Bradford, and tenor saxophonist Redman take center stage with their solos. There simply isn’t a song on Science Fiction that fails to grab my attention.

Science Fiction is an album I’ll need to spend more time with in order to properly digest. My lone critique of it now is that because of the shifting line-ups, it feels scattershot from song to song. I could have easily done with an album of Asha Puthuli vocals, an album of crazed solos from Billy Higgins and Charlie Haden, or an album of tripled solos from Coleman, Dewey Redman, and Bobby Bradford. Getting all three, in addition to the usually sparkling contributions from Don Cherry and the bizarre poetry of the title track, is a blessing and a curse. Ten listens down the line, perhaps it’s more of one than the other.

|

2. Russian Circles – Geneva 2LP – Sargent House, 2009 – $24 (Newbury Comics, 1/6)

Perhaps the biggest statement here is that I bought the new Russian Circles album, not the new Pelican album. The comparison isn’t as unavoidable as it was when Russian Circles debuted with Enter in 2006 in the wake of The Fire in Our Throats Will Beckon the Thaw, but even if you Google “Russian Circles,” the info text for their own web site includes “similar to fellow Chicago residents Pelican.” That’s a strange combination of deference and realism—yes, we also play instrumental post-metal/rock, yes we’re from the same city and formed after they did, yes they’re a higher profile band. But the tides have turned with regard to their respective standings. Seemingly every conversation about Pelican begins and ends with a derisive comment about drummer Larry Herweg, which leads Pelican fans to seek other options for their post-metal fix.

(Side note: I don’t think “post-metal” fits the current output of either band, but it’s still the prevailing genre tag. I’ll give Pelican’s first two releases, the self-titled EP and Australasia, some leeway given some doom-metal tendencies, but since The Fire in Our Throats they’ve been much closer to Explosions in the Sky. Russian Circles was mostly in the post-rock camp on Enter and at this point, I’d limit their connection to metal to a pinky toe.)

The tired “Pelican’s drummer sucks” argument isn’t at the heart of why I enjoyed Australasia and The Fire in Our Throats and was so disappointed by City of Echoes and What We All Come to Need, or why I greatly prefer Russian Circles’ Geneva to those two recent Pelican albums. The issue is scope. After The Fire in Our Throats, Pelican decided that they were done with writing ten-minute-long epics and pared their compositions down to more manageable sizes. This knee-jerk, “let’s change for the sake of changing” decision removed the drama from their songs, making even four-minute tracks plod. I simply don’t know who prefers a four-minute Pelican song with a tidier structure to a mammoth beast like “March into the Sea,” which still amazes me with how many riffs and ideas it crams into its running time. Even recruiting Shiner / The Life and Times vocalist Allen Epley to sing on What We All Come to Need’s dirge-like closer, “Final Breath,” which should have been a merger made in fanboy heaven, was ultimately underwhelming. Why can’t he sing over a song I care about? The songwriting is the main issue here, not Herweg’s drumming.

Fortunately, Russian Circles stole Pelican’s scope for Geneva. (My dad loved telling me about what happened when his favorite baseball player growing up, Duke Snider, moved out to Los Angeles along with the rest of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Snider was heading out onto the field at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum when Willie Mays pointed at the 440-foot-deep right field wall and yelled, “Duke, they stole your bat!” Ebbets Field in Brooklyn only had a 297-foot-deep right field pole. Snider’s power numbers stayed there.) An even bigger slight—the majority of these songs have comparable runtimes to the tidied Pelican tracks. The reason why Russian Circles succeeds with this set-up and Pelican fails is that the former group recognizes its weaknesses and accordingly plays to its strengths. Drummer Dave Turncrantz is the best musician in Russian Circles, so everything runs through him, especially on the dynamic, foreboding opener “Fathom.” Bassist Brian Cook fills the low-end with the appropriate texture for a given song, whether it’s the rumble of a held note, a distorted lead, or the melodic anchor on the bridge of “Philos.” Guitarist Mike Sullivan isn’t as nimble as the riff-machines in Pelican, but he can carry a song like “Malko” with his razor-sharp leads. More importantly—and he deserves a ton of credit for this move—he lets contributing instruments like violin, cello, trombone, and trumpet take the lead during the beginning of “Fathom,” the entirety of the wonderfully lulling “Hexed All,” and the triumphant peaks of “Philos.” When I first heard Geneva, I dismissed it as Pelican with strings, but the ways these elements take charge, set the atmosphere, or lock in with Sullivan gives the album a much longer shelf-life. Unlike the recent Pelican output, where I’m likely to single out the most memorable element of a song—usually a guitar riff like the Hum-on-steroids “City of Echoes”—everything here serves the song and the album as a whole.

Part of me hates framing the discussion of Geneva with the ongoing comparison with Pelican, but seeing Russian Circles come out from under Pelican’s shadow and actually surpass them by a wide margin is a huge achievement. Since Enter, Russian Circles have been a group that’s very good at what it does, but Geneva changes the discussion. Now I’m considerably more excited for the next Russian Circles album than the next Pelican album. There’s no longer any question who has the scope and the songwriting in Chicago.

|

|

I kicked off the new year with an eBay purchase. In case you're wondering, I'm changing the title format of this year's iteration of The Haul to emphasis the bands mentioned.

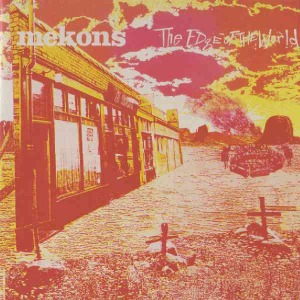

1. Mekons – The Edge of the World LP – Sin, 1986 – $9.50 (eBay)

I just can’t stop buying Mekons albums. The Edge of the World is the eighth Mekons LP I’ve picked up in the last few years, following So Good It Hurts, Mekons Rock ‘n’ Roll, I Love Mekons, Honky Tonkin’, the Crime and Punishment EP, The English Dancing Master EP, and the consistently great Fear and Whiskey. Much like similar obsessions with Cocteau Twins, Wire, and Brian Eno, the Mekons offer a large discography, solid risk/reward pay-offs, and—with the exception of this album—frequent appearances in used LP bins.

Consistency is a strange thing with the Mekons. Every one of these releases is interesting, but not necessarily consistently good. Fear and Whiskey manages to push off in different stylistic directions without suffering a misstep, but most Mekons albums have a significantly lower batting average, especially the EPs. The Edge of the World breaks this trend. It’s consistently good, but aside from “Alone and Forsaken,” less frequently great. It’s an extension of the Fear and Whiskey’s alt-country, but now they feel like the house band in that run-down English saloon.

|

|

This entry follows up part 1 on the group’s 1980s albums, part 2 on the group’s 1990s albums, and part 3 on the group’s 2000s albums. Read those if you’re interested in Sonic Youth the Rock Band.

Having built their own studio in 1996—thanks, major label cash—Sonic Youth realized their dream of being able to record whatever they want and release it on their own label, Sonic Youth Recordings (creative name, guys). They kept recording “real” Sonic Youth albums, although Washing Machine, A Thousand Leaves, and NYC Ghosts & Flowers certainly reflected this new emphasis on their experimental/avant-garde tendencies, but the SYR releases aren’t concerned with traditional rock songs. These releases bring in different collaborators, different line-ups, and different contexts for Sonic Youth’s music.

Considering the wide range of reactions to these releases—ranging from praise of their high-art leanings to dismissal of their pretentious wanking—I approach this series with trepidation. I’m sure there will be some catchy pop songs in here to keep my spirits up, at least!

This entry covers the first four SYR releases. I may or may not ever get to the next four.

SYR 1: Anagrama – SYR, 1997

Highlights: “Anagrama,” “Tremens”

Low Points: “Mieux: De Corrosion”

Overall: The first SYR EP seems like a walk in the park to what’s coming up. “Anagrama” leads off the EP with nine-and-a-half minutes of gradually developing instrumental rock. Its gentle chords provide some pleasant melodies along the way. There’s a clear structure to its noisy crescendo, although the song strays from this course in its closing minutes. It’s a nice bridge between Washing Machine and A Thousand Leaves and definitely worth checking out. The title of “Improvisation Ajoutée” suggests a practice-room take, but the resulting three-minute song reins in what could have been an interminable jam. Nice textures, if somewhat unmemorable. “Tremens” is another short song, a woozy, scraping post-punk instrumental held together by Shelley’s back beat.

Only “Mieux: De Corrosion,” the EP’s final song, is particularly abrasive. A mixture of oscillating noise, muted drumming, piercing guitar stabs, and well, more noise, “De Corrosion” is the group’s gateway to the noise scene. I prefer light doses of noise tempered by melody—the pointillist landscape of Accelera Deck’s Pop Polling, Tim Hecker’s last two LPs, Nadja’s noisy doom-gaze—so this strict dosage is too heavy for my tastes.

SYR1 starts off this series with relative optimism. The danger of the SYR series is that it’ll be used as a dumping group for rehearsal tapes and not as a reason to turn those unfinished ideas into something concrete. Only “Anagrama” sounds like a finished product, but the other three songs have enough ideas and intriguing textures to justify their release. Part of me is amazed at Sonic Youth’s restraint—this EP could have easily been a double CD, given their propensity for stretching out, but that itch will be scratched on the next few SYR releases.

SYR 2: Slaapkamers Met Slagroom – SYR, 1997

Highlights: “Stil”

Low Points: “Herinneringen”

Overall: Picking up quite literally where SYR1 left off, the opening strains of “Slaapkamers Met Slagroom” extend the oscillating noise of “Mieux: De Corrosion.” Soon enough, however, strains of an actual song, specifically the much-loathed “The Ineffable Me” from their then work-in-progress A Thousand Leaves, trickle though. Thankfully void of Kim Gordon’s irritating vocals, “Slaapkamers” drifts in and out of the main “Ineffable” riff a few times before moving onto an extended jam for most of its seventeen-minute runtime. Fine background music with cool guitar noises and minimal structure, “Slaapkamers” reminds me of Tarentel—both the spaced-out early stuff and the psychedelic jams they’ve been rocking recently. It also reminds me that I’d rather listen to From Bone to Satellite. “For Carl Sagan,” now there’s an extended jam.

The other two songs are similarly improvised. “Stil” stumbles onto the melody from A Thousand Leaves’ “Snare, Girl” a few times, a pleasant foreshadowing of its lilting grace. The background clatter fills whatever noise quota is mandated by the series. “Herinneringen” closes SYR 2 with some scattered Kim Gordon vocals. Occasionally she stumbles across some actual words—“Please believe me” comes up near the end—but most of it is mumbled syllables and quiet growling. There’s one part that goes, “Dar… dar… dar... grrrrrr!” that makes me laugh a little, but otherwise the track is quickly forgotten.

SYR 2 raises a big question for this series—does improvisation equal avant-garde? So far I’d say no—it’s hard to think of these tracks as anything more than Sonic Youth’s occasionally interesting rehearsal tapes, especially given the appropriation of two of these riffs for 1998’s A Thousand Leaves. This distinction doesn’t mean that these EPs haven’t been valuable or interesting—it’s certainly a cool look inside their practice space, into the stretched-out jams that germinated their songs during this period—but it’s easier to deem them a welcome indulgence than a taste of the avant-garde.

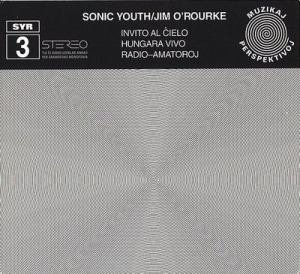

SYR 3: Invito Al Ĉielo – SYR, 1998

Highlights: All three tracks are reasonably good

Low Points: Kim Gordon’s spoken word bits

Overall: SYR 3 is the first release in the series that establishes itself as fundamentally separate from Sonic Youth’s DGC output. No longer sounding like jam sessions to be shaped into form for A Thousand Leaves or cut outright; SYR 3’s humming drones and free-jazz tendencies steadfastly avoid the signatures of Sonic Youth’s sound. Whether this development is an improvement depends a lot on your appetite for twenty- and thirty-minute soundscapes, but there’s more lasting value here than on previous SYR EPs.

SYR 3 marked the first collaboration between Sonic Youth and Jim O’Rourke, preceding his production credit for NYC Ghosts & Flowers and his official stint in the group for Murray Street and Sonic Nurse. O’Rourke’s solo output had not yet hit the 1970s pop ease of Eureka and Insignificance, nor do his contributions here resemble the acoustic folk ruminations of 1998’s Bad Timing and 2009’s The Visitor. Instead, SYR 3 draws upon the Jim O’Rourke I don’t know, specifically his work with Gastr Del Sol and Brise-Glace and his 1990s solo albums. The result recalls the most skeletal, avant-garde moments of Sonic Youth’s catalog—the minimal moments of Confusion Is Sex, the drone of Bad Moon Rising—stripped absolutely bare.

Mentioning the specifics for these songs seems like a losing battle with such a prevailing emphasis on atmosphere, but I’ll try anyway. “Invito Al Ĉielo” starts out with a mixture of haunting drones, deflated trumpet (performed by Kim Gordon), and electronic squiggles, then switches gears into a very muted jazz beat at the seven-minute mark. From there, Kim Gordon performs some hazy spoken word, mixed very low in the mix, while guitars wriggle out of their tunings and someone, presumably O’Rourke, manipulates an audio recording in the background. “Hungara Vivo” is the most soundtrack-ready piece, as ringing bells, guitars, vibes, whatever, run in place, gradually replaced by further tape manipulation. The near thirty-minute closer “Radio-Amatoroj” carries the most forward momentum, rumbling through some scratchy guitar riffs before lurching forward, ever cautiously, at the twenty-two-minute mark and almost sounding like a skeletal rock song. It reminds me of Matmos’s “The Precise Temperature of Darkness” reimagining of Rachel’s “Full on Night” from their two-track Full on Night EP. Both songs hinge on electro-acoustic noise creating a profound sense of unease, bordering on distress.

SYR 3 is an unforgiving piece of avant-noise. Sonic Youth and Jim O’Rourke give you practically no rock pay-off, only fleeting moments of beauty, and stretch two of these tense tracks to epic lengths. That’s precisely why I enjoy it. SYR 3 succeeds where the rehearsal takes of SYR 1 and SYR 2 fail: it actually shows another side of the band. Not just the unedited side, the rough cut side, but what could very well be an entirely different group, one that’s focused on atmospheric, textural noise. If you come to SYR 3 hoping for an extension of Washing Machine or A Thousand Leaves, you will be sorely disappointed, but if you’re at all curious about ambient noise recordings, SYR 3 provides a convenient in for this scene.

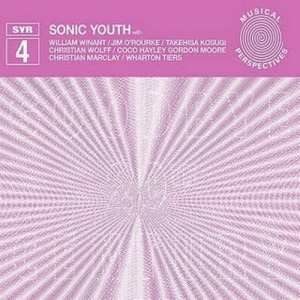

SYR4: Goodbye 20th Century – SYR, 1998

Highlights: “Having Never Written a Note for Percussion”

Low Points: Most of it is very trying

Overall: If SYR 3 whet your appetite for avant-garde compositions, boy does the rock band Sonic Youth have a deal for you. SYR 4: Goodbye 20th Century is a double album of covers, sorry, reinterpretations, of notable contemporary composers like Christian Wolff, John Cage, Steve Reich, and Yoko Ono, with the musical collaboration of avant-garde artists like Jim O’Rourke, William Winant (Mr. Bungle connection alert), Christian Marclay, and others. It’s the ultimate credibility recharge after their alternative/grunge indiscretions on Goo and Dirty, a love letter for and apology note to the NYC art-scene that spawned them. Much has been made of Sonic Youth’s referential streak, whether expressed in lyrics, liner notes, or interviews, but nothing they’ve done so far has been this explicit. Why record this album? Why release it? Here are some potential reasons.

1. To pay homage to contemporary composers they love. It’s fine to have favorite contemporary composers, to be influenced by their ideas and specific pieces.

2. To get back to their roots in avant-garde classical music. That’s a direct quote from SYR’s web page. Lee Ranaldo and Thurston Moore participated in Glenn Branca’s guitar armies when Sonic Youth was first forming, so technically this is true. I don’t recall any of their early albums actually sounding like avant-garde classical music, however.

3. To expose these composers to a new audience. How many times have you cried out because “more people should know about this music,” whatever that music may be? Sonic Youth recognize the extent of their power of exposure and utilize it here.

4. To test their audience. SYR 4 continues the groundwork laid by SYR 3’s exploration of avant-noise and tests their core audience’s interest in (or patience for) avant-garde classical music.

5. To get away from guitar rock. Goodbye 20th Century was released in between A Thousand Leaves, one of their most mellow LPs, and NYC Ghosts & Flowers, their most explicitly art-rock LP. To say that their interested in the more traditional elements of rock music had waned is an understatement.

There are certainly other possibilities here. I tried to be as diplomatic as possible above, since I’m of a split mind regarding Goodbye 20th Century and it’s too easy to lean on the knee-jerk “This noise isn’t Sonic Youth” button for humor. I’ll try my best to hold off on that response until the end of the program.

I will be entirely honest: this context does not suit Goodbye 20th Century. YouTube clips wouldn’t have done the fantastic SITI Theater performance of Rachel’s Systems/Layers justice and similarly, trying to rush through Goodbye 20th Century without tracking down the original pieces, reading up on the artists’ intents, or seeing it performed in many ways defeats the purpose. On several occasions, specifically during the opening performance of “Edges” by Christian Wolff, I imagined how much more sense this collection would make as an art installation or theatrical production. Being handed these pieces (originally typed “songs” but quickly recognized my error) without proper context, without proper education, provides too quick of a path to the knee-jerk dismissal that so many listeners will gladly evoke. One could easily accuse me of over-thinking here, of mistakenly believing that one needs to enter this world with adequate background when a blank slate is perfectly fine, but if I learned anything from the more challenging texts covered in graduate school, it’s that the more you know going into them, the more you will learn during the process.

It’s not like certain pieces here aren’t compelling without the proper schooling. The clanging noise swarm crescendo of James Tenney’s “Having Never Written a Note for Percussion” condenses the unease of SYR 3 into a remarkably effective nine minutes. All three John Cage pieces tease with fleeting beauty, absorbing textures, contradictory elements. But it’s the second layer of appreciation—“I see what they’re doing here, how they’re interpreting this piece”—that’s lacking. I could pick up a sense of humor within John Cage’s “Four6,” but isn’t humor the response listeners are naturally ashamed to invoke when encountering (supposedly) high art? Stock joke: Square guy walks into a pretentious art gallery, laughs at something in the piece, all of the other patrons shun him, and then the artist emerges and confirms his intent for humor, thereby justifying the square guy’s gut reaction. Conceivably Thurston and Kim chose their young daughter Coco to perform Yoko Ono’s “Voice Piece for Soprano” for this very reason—to show that this isn’t a strictly serious endeavor, that some fun can be had—but is that the lone interpretation?

This Perfect Sound Forever interview with Thurston Moore circa 2000 shows how genuine his interest in this material is. I don’t doubt him. His excitement over being able to perform these pieces without classical musical training is particularly inspiring; he mentions how “this music was more punk rock than any punk rock music ever was,” an understandable point given the respective differences between classical and contemporary compositions and rock and roll and punk rock. Yet I disagree with his assessment of the audience in two spots. First, when asked whether electronic music (presumably his banner term for these styles) has influenced other styles, Moore responds:

It's influenced the musicians. Most of them are aware of that stuff. I don't think the general populace is. The general populace isn't historically musically adventurous. A classic example is David Bowie who will always employ things like that into his music and then he sells billions of records. The Beatles did the same thing.

What Sonic Youth did before Goodbye 20th Century falls in line with both the Beatles and David Bowie: by pulling in non-rock influences, they made their own rock music much more inventive, more rewarding. Where Sonic Youth departs from this mentality on SYR 4 is in dropping the application of these ideas in favor of presenting the pure, unfiltered ideas. I immediately think of side B of David Bowie’s Low, the largely instrumental, decidedly non-pop venture into electronic composition. Yet even Low had a closer proximity to its influences: Brian Eno, Tangerine Dream, Neu!, and Kraftwerk are now viewed as Eno’s contemporaries. Would Sonic Youth themselves ever rank John Cage and Steve Reich as their contemporaries? Their most strident fans might, but I find the distance too great given albums like Dirty and Rather Ripped.

I keep mentioning distance, since that’s an absolute essential aspect of listeners’ expectations. When I first heard My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless, I thought it was a new age album because of the vocals and guitars. I’d heard bands influenced by MBV at that point, but the genuine article was still striking. Extrapolate that response to the gap between Sonic Youth and the contemporary composers covered here. Sticking purely to Sonic Youth’s “official” releases, only Confusion Is Sex, Bad Moon Rising, and NYC Ghosts & Flowers take a remotely similar approach to these pieces, but each of those albums is still dictated by rock conventions, whether recognizable vocals, guitars, or rhythms. Goodbye 20th Century avoids all such conventions. It challenges the boundaries of what’s music and what’s not. Certainly many people would put these pieces in the “not” category. Yet from the same interview, Thurston Moore imagines a different response:

I think there's a large demographic of Sonic Youth's audience that has no real knowledge of that world of music. I think, like anything we do, it will lead people if they enjoy what they're listening to do their own research. We've always been into that. We go on tour and have more radical kind of music play on the same stage as us that wouldn't normally play on these stages and expose the audience to this music. Generally, be it electronic music or free jazz or dadaist noise… The audiences who will come see Sonic Youth, like an audience coming to see Pearl Jam or whatever, that kind of person who'll come see that kind of band, they'll generally hear this kind of music and it's great. It's not like a bunch of jerks onstage making noise, there's some sort of purposeful compositional quality to it. It strikes them as... something else.

Whether based in faith or eternal optimism, Moore envisions releases like Goodbye 20th Century being a gateway to this other realm, that the natural reaction to the “something else” is intrigue. My reaction simply isn’t. Although I don’t turn to the disgust or revolt of many listeners, I also don’t feel remotely compelled to track down any unfamiliar composers. Instead I wonder what could’ve been—if these pieces had the proper context, if they’d chosen less abrasive selections, if it felt like less of a test for their audience and more like a reward.

|

|